The statistics don’t lie: while the UK's historic COVID-19 vaccine rollout has administered more than 50 million jabs across the country so far, not every community has benefited equally.

Specifically, uptake among Black, Asian, and minority ethnic Britons is lower than that of their white counterparts in every age group, according to data from Public Health Wales.

Take, for example, adults aged 55-59 in the UK. So far, 89% of white people in that age group have received one dose. But for those from a Black, Asian, and minority ethnic background, that number stands at 77%.

This corroborates initial research conducted in 2020, ahead of the rollout. Just 39% of Black and minority ethnic Londoners said that they were likely to take the vaccine, according to a poll by Queen Mary University London. Whereas for white people, that number stood at 70%.

There's a conversation to be had about why this is the case. According to experts, it's an oversimplification to suggest it's simply to do with the COVID-19 vaccine itself. The question goes much deeper, over a far longer stretch of time.

"We need to start with the question that looks at which groups in society have been historically marginalised to the extent that their confidence levels in health services or in vaccinations is pretty low," Dr. Halima Begum, the CEO of the Runnymede Trust, a UK think tank that focuses on racial injustice, told Global Citizen. Begum has been working as an individual on race, education, and global development for decades.

Begum says the NHS is driven by demand, meaning that "those who shout loudest" will access the most services. In this instance, race and class are linked — those who live in more vulnerable environments, or have learned to trust the health system less, will have their voice diminished.

In such communities, trust has slowly been eroding in the NHS for decades through consistently worse health outcomes. One commonly referenced example is on racial discrimination in maternity care. Black women are four times more likely to die during childbirth than white women in Britain today. So how do you start to earn this trust back?

“You have to not ridicule people who might be reluctant about taking the vaccine,” Begum says. “You have to answer their questions — good public health questions around safety and efficacy.” She later adds: “A mature democracy should be able to answer those questions and rebuild that confidence.”

She says that the UK government should be doing more to reach these communities. It could be done through ideas like mobile vaccination units to reach the most isolated, dialogue with community leaders, or by taking doctors directly into the community.

What does institutional racism in the UK have to do with lower COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Black and ethnic minority communities? We asked Dr. @Halima_Begum, CEO of the @RunnymedeTrust, a race equality think tank.

— Global Citizen UK (@GlblCtznUK) May 7, 2021

Learn more about the issue here: https://t.co/epaCqil2eA#VaxLivepic.twitter.com/38bNTAvw4C

Begum points to the priority groups for the COVID-19 vaccine. Although age is a crucial factor for groups who are at-risk, she highlights that the government has never considered offering vaccinations by ethnicity, despite the statistics showing that minority communities are disproportionately more at risk.

"It's almost as if the responsibility for getting better and healthier and staying safe rests individually with those communities,” Begum says.

That lack of faith in the NHS is also connected to a wider lack of faith in institutional power itself — for example, through racialised outcomes in policing, criminal justice, or immigration. "It's not easy when historically you see authorities as not having had your back,” Begum says.

There are countless examples showing this to be true. The independent inquest into the death of Stephen Lawrence in 1993, called the Macpherson report, found that there was a culture of institutional racism in the police force. But its recommendations were resisted, and since then there have been a multitude of fresh controversies, from disproportionate use of tasers to a "discriminatory" police database on suspected gang members.

On criminal justice, Black people accounted for 12% of the total prison population in 2015/16, despite only making up 3% of the population of England and Wales. And on immigration, the Windrush scandal of 2018 goes some way to showing how migrant communities have been mistreated by authorities across generations.

So given the link between distrust in political machinery and suspicion surrounding a vaccine rolled out by the state, a much-criticised report on race from the UK’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities possibly could not have come at a worse time. Published on March 31, it downplayed the presence of systemic racism in Britain, and praised the UK as a “model for other white-majority countries.”

Its findings were rejected by a vast swathe of campaigners and experts for “white-washing” the issue, including the Runnymede Trust and Black Lives Matter UK. Human rights lawyers at the United Nations criticised the report for “twisting data and misapplying statistics” in an attempt to “normalise white supremacy.”

“Quite a lot has happened in the last year,” Begum says. “I think the public’s understanding and sentiment of where we are on racism is significantly advanced… so the public wants to have a conversation around structural racism and institutional racism. What we now see is perhaps a commission-driven process that is behind the public sentiment and public will.”

However, more than a dozen Conservative MPs have since written to the Charity Commission to uniquely criticise the Runnymede Trust for its condemnation of the report, alleging that it was pursuing a political agenda. The Trust described the response as part of an “adversarial trend” for politicians to file official complaints against charities they disagreed with, like the National Trust, for example, who were subject to attacks from the media after releasing a report addressing the links between the buildings it cares for and ties to past slavery and colonalism.

"I was disappointed,” Begum adds on the race report. “I will come back though to say that the public on the whole is united in its response to that commission. That's where I see a space for hope: the public is way more advanced in its understanding of institutional racism."

This has everything to do with vaccine hesitancy in ethnic minority communities. Ultimately, it did little to advance the cause at hand: improving the necessary trust in political systems that is crucial to restoring the faith of historically marginalised people in public health. In fact, it possibly served to exacerbate the problem.

“It does undermine public confidence, and it does indeed undermine confidence in Black and ethnic minority communities," Begum says. "It has eroded trust. However, we've equally seen how anti-racism allies have come together to say, we've got this. We understand, we all acknowledge how difficult this year has been, and we all understand what disproportionate outcomes in the health system means for Black and ethnic minority communities.”

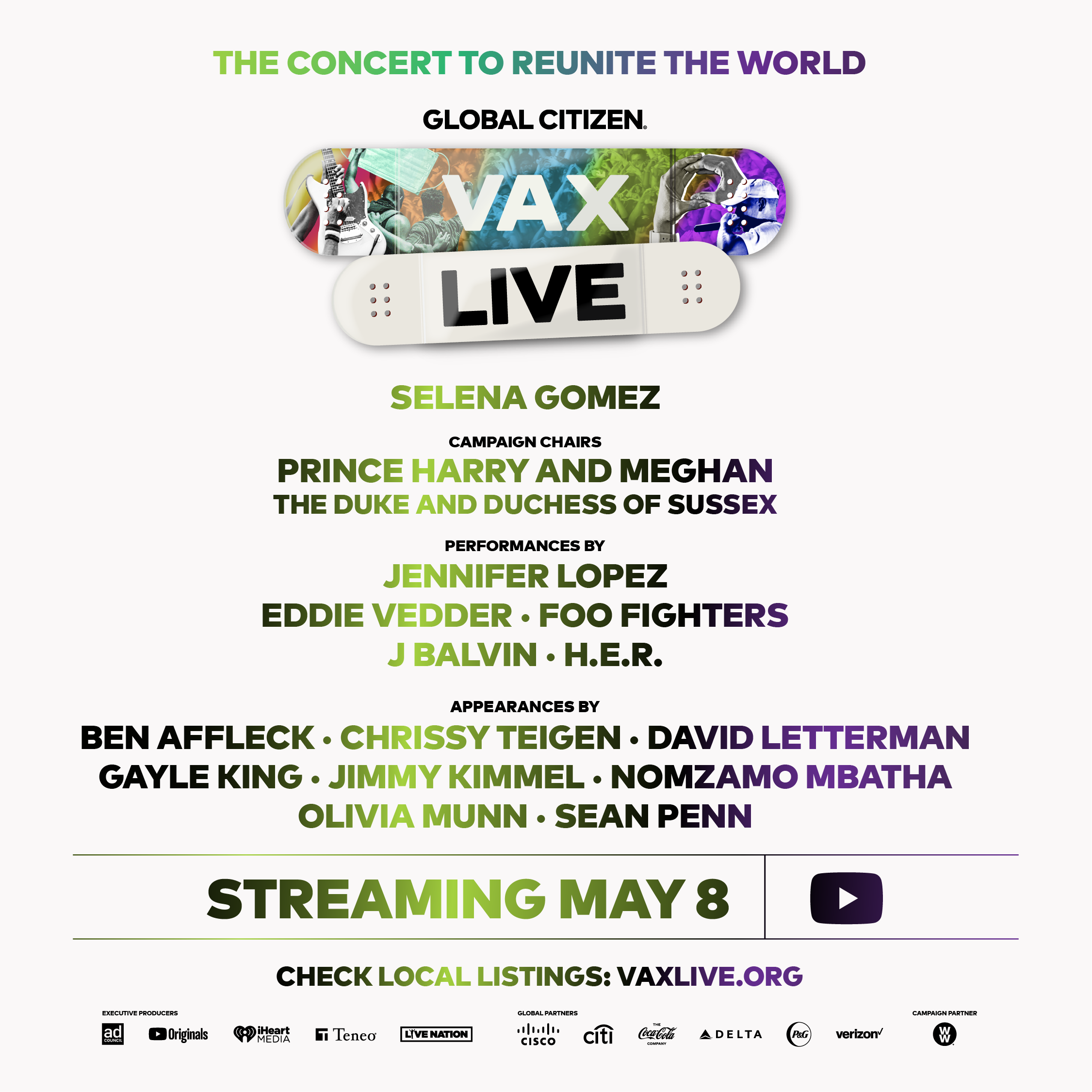

As part of Global Citizen’s Recovery Plan for the World campaign, VAX LIVE: The Concert to Reunite the World will bring together artists, entertainers, world leaders, and more to ensure equitable vaccine distribution around the world, tackle COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and celebrate a hopeful future.

Find out how to tune in here, and join us in taking action to end the pandemic and ensure that everyone, everywhere has access to COVID-19 vaccines. Then, head to our multimedia hub VAX BECAUSE to join candid conversations about the pandemic and find answers to your biggest questions about the vaccines.

Want to take home part of the show? Check out our VAX LIVE merch at the Global Citizen official store.