The first time Marvin Mayfield was arrested, at age 22, he was arrested on suspicion of burglary — a crime he says he did not commit.

A Brooklyn native, Mayfield was taken to Rikers Island in New York City — notorious for its poor living conditions and treatment of detainees — where he stayed for months, despite not having been convicted yet, because he could not afford his bail. After being abused by jail staff and beaten by fellow detainees to the point of having a broken leg, he gave up.

“I pled guilty to the charge because I couldn't get out of jail,” he told Global Citizen. “I think that was the cruelest blow of anything — to have to say, ‘Hey, I did it,’ even though I didn’t because I didn't have money for bail, no one was going to post bail for me, and I couldn't get out.”

Mayfield would go on to spend years going in and out of the prison system while living with an addiction. Nearly every time he was arrested and charged, he could not afford his bail, languishing in jail awaiting trial or, far more likely, a plea agreement. At one point, he faced a bail of $75,000 for a nonviolent crime.

His story is not an uncommon one.

Approximately 2.3 million people are incarcerated across the United States. About 465,000 of those people are sitting in jails around the country while not yet convicted of a crime, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. And the overwhelming majority of them are there — and will remain there for days, weeks, months, and, in some cases, years — because they cannot afford to make bail.

Intended to be an accountability mechanism to ensure that people returned for their court dates, the cash bail system has become a tool that criminalizes poverty. Cash bail keeps those who can least afford to be kept from their jobs and families in jail, while those who do have the means to make bail are allowed to return to their lives, roam free, and actively participate in their defenses ahead of their trials. And this system, as well as mass incarceration in the US, hits communities of color and people living in poverty (often overlapping demographics) the hardest.

“If you have a person who is poor and black and commits the same crime as a person who is wealthy and white — one stays in jail and the other doesn't. Tell me how that's justice,” said Mayfield, now 57 and a campaign leader at JustLeadershipUSA, a nonprofit dedicated to cutting the US correctional population in half by 2030.

“We don't believe that's justice at all, so we wanted to eliminate a monetary bail system,” he added.

On March 31, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and state lawmakers finally passed legislation that eliminated the use of cash bail in New York for most misdemeanors and nonviolent offenses, which make up the majority of charges in the state.

“When I got that news I felt like … Am I hearing this correctly?” Mayfield recalled. “I was just so elated — like wow, we actually did it.”

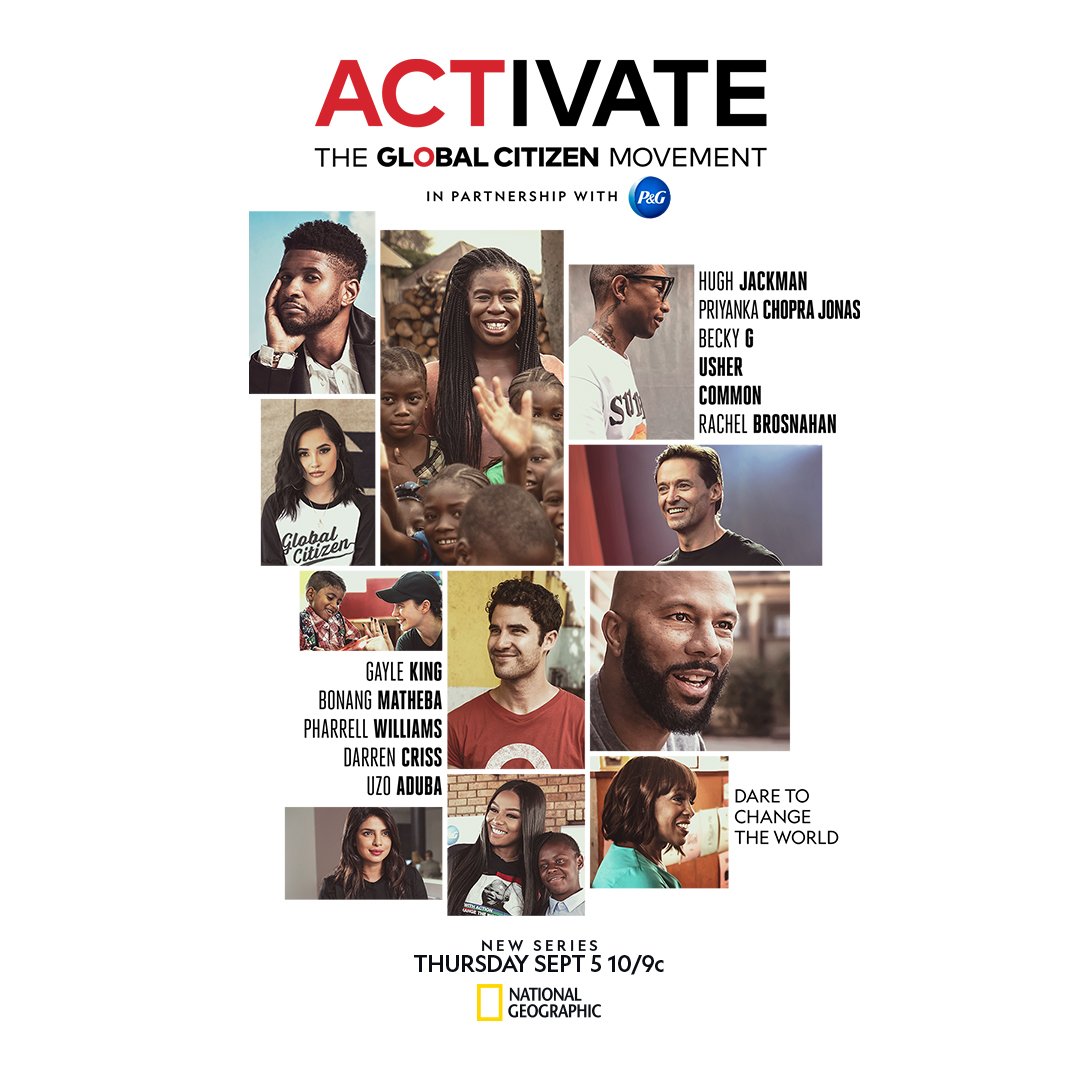

For two years leading up to the news, Mayfield did everything from handing out flyers in neighborhoods and speaking to people on street corners to meeting with senators and assemblymen in Albany to advocate for an end to cash bail. His efforts — and his personal story — are followed in the second episode of the docu-series ACTIVATE: The Global Citizen Movement, airing on National Geographic and online this Thursday, Sept. 12.

When the legislation finally passed, Mayfield said he thought of all the people he had worked with as part of the #FREEnewyork campaign, led by a coalition of grassroots organizations including JustLeadershipUSA, to get to this moment.

“The little kids and senior citizens, and everyone in between, who took the bus up to Albany to rally, chant, hold signs, and picket outside the governor’s office … It was all worth it,” he said.

Mayfield at a rally in Albany.

Mayfield at a rally in Albany.

But, Mayfield, a self-professed skeptic, said the feeling of triumph is tempered. He remains acutely aware of the fact that the legislation doesn’t apply to everyone.

“The thing is that everyone, no matter what they were charged with, is entitled to due process and the presumption of innocence,” he said, explaining that some charges are considered violent offenses by legal definition, regardless of whether actual violence occurred during the incident. For example, robbery in the second degree is considered a violent offense, even if no violence took place during the alleged crime.

Mayfield also pointed out that while someone may initially be charged with a violent offense, they have not yet been found guilty and should not be detained. Through the plea bargaining or trial processes, they may have their charge reduced to a lesser one — and this lesser charge may not be eligible for cash bail under the new law. The problem is, by this point, a person who cannot afford to make bail will likely already have spent a prolonged period of time in jail, and may have lost their job or housing as a result.

And while detained or incarcerated, it is exceedingly difficult for people to participate fully in their defense, which can lead to worse outcomes with long-term consequences.

“When you're detained and pending trial, you do not have the same liberty or ability to prepare a defense for yourself, and that means that when you're sitting in jail and waiting, you're at the mercy of district attorneys, especially if you don't have money for a private attorney,” Mayfield said.

While jails and prisons typically have law libraries intended to enable detainees to better understand their case and participate in their defense, he explained, most libraries have inadequate resources and many detainees don’t have the skills they would need to make use of those resources.

“If a person doesn't have a GED or is uneducated, you're gonna give them tomes of law books so they can prepare a defense of themselves? It’s not going to happen,” Mayfield said.

“And, when you walk into the courthouse in chains [from jail], there is automatically a stigma and a presumption of guilt when you walk in in handcuffs. But when you walk in as a free person on bail or released on your own recognizance and you’re dressed decently, there is a completely different perception of who you are,” Mayfield added.

He said he and fellow #FREEnewyork campaigners are still hoping to see a full elimination of the cash bail system and will continue to advocate for an end to the use of money bail in any case by empowering those who are directly impacted to make change.

“We believe that the people that are closest to the problem are closest to the solution, but furthest away from the resources,” he said, adding that JustLeadershipUSA aims to connect those people with the resources they need to be changemakers in their communities and at the state level.

Mayfield at a rally.

Mayfield at a rally.

“Nothing, nothing, nothing is ever changed without the people who are most directly impacted standing up and saying, ‘You know what? I've been affected by this and I'm not going to stand for it anymore. I want to make changes in my life and the lives of my family,’” he said.

That is precisely how Mayfield felt when he left prison for the last time. Once free, he said he was motivated to change and learn about the system that had “wrecked” his life. Having been swept up in the “War on Drugs,” Mayfield said he quickly realized that black and brown communities are policed differently, tending to have more a greater police presence and more arrests for drug-related offenses, even though statistics show that white and black people use drugs at similar rates.

“I came to this organization directly coming out of prison myself. And when I got out, I decided that I wanted to make a change and the first person I had to change was myself,” he said.

“And though, not for one moment, do I think that I am not responsible for my actions … But I also realize that there are certain conditions in my community that led to me falling into this so-called trap that was set for me,” he added.

In the largely black and brown communities that Mayfield works in — Harlem, the Bronx, and Brooklyn — involvement with the criminal justice system is the norm.

He said when he goes into housing projects to speak to communities about ending cash bail and advocating for criminal justice reform, nearly everyone has been affected by Rikers Island, cash bail, or the criminal justice system more broadly.

“So they all know about the issue, but the one thing they don’t know is that they have power — they have a voice and that voice can be heard. And if we mobilize people, motivate and organize people, they can actually make change,” he said.

But it’s not always easy to get people, particularly people who have been directly affected, involved.

“When we say we're going to get on a bus ... and we're going to go to Albany with the state troopers with their big Smokey Bear hats on, a lot of people are intimidated, especially if they’ve already been involved with the system, if they've already been to prison, if they've already suffered trauma at the hands of the people who are supposed to uphold the law for them right,” he said.

That’s usually when he shares that he, too, has been affected.

“We have to let them know that we've been there. I have been personally affected. I've been to prison. I've sat in a jail cell. I've been abused by the people who are supposed to handle my care custody and control,” he said.

“So I understand and I know why you're afraid, but we have to get through that if we're going to make any changes at all."

He encourages people to start small. Read up on these issues. Learn about the facts and figures. Arm yourself with information. Take a flyer. Maybe hand one out.

Mayfield is awaiting Jan. 1, 2020 — the day the new legislation that will end cash bail for many goes into effect — with bated breath.

“Like I said, I’m a skeptic. So I go back in history when the Emancipation Proclamation was issued and slavery was abolished, but seven or eight years later federal troops had to go in and actually liberate people who were still on plantations,” he said. “So until these jail cells start emptying out and decarceration is a real fact and promises are kept, I’m going to hold off on my full joy.

“But to have this legislation passed in the first place and have governors and politicians say, ‘OK, we stand with you on this, we’re going to make this happen,’ was monumental,” he added.

Today, Mayfield is a student at both Columbia University and New York University with plans to study criminal justice further. And he and his wife are foster parents, supporting at-risk youth. He hopes to one day start his own organization to help children, particularly teens, affected by the criminal justice system.

But in the meantime, Mayfield plans to continue using his voice to advocate for greater justice and equality for all.

“Even though we have gained this historic legislation," he said, "it’s not over until everyone has a fair chance and until no one can say they got railroaded by the courts or the system."

How to Tune In

ACTIVATE: The Global Citizen Movement airs weekly in select markets beginning Sept. 5 on the National Geographic channel or globalcitizen.org/activate. You can watch the second episode, on ending cash bail, here.

ACTIVATE: THE GLOBAL CITIZEN MOVEMENT is a six-part documentary series from National Geographic and Procter & Gamble, co-produced by Global Citizen and RadicalMedia. ACTIVATE raises awareness around extreme poverty, inequality, and sustainability issues to mobilize global citizens to take action and drive meaningful and lasting change. The series will premiere globally in fall 2019 on National Geographic in 172 countries and 43 languages. You can learn more here.