Editor’s note: This story includes details of sexual violence.

When Samra Zafar was 16 years old, her mother came into her room and told her she’d received a marriage proposal.

“I was doing my math homework,” Zafar, now 36, told Global Citizen. “I was just sitting at my desk, doing my homework.”

They lived in Ruwais, a small town in the United Arab Emirates. The man she would marry, she came to learn, was a family friend’s brother who lived in Canada. Her mom told her it was a good way for her to be able to get a university education and to be taken care of. It wasn’t up for debate — the plans would soon be set.

Take Action: End Child Marriage in Pennsylvania This Year

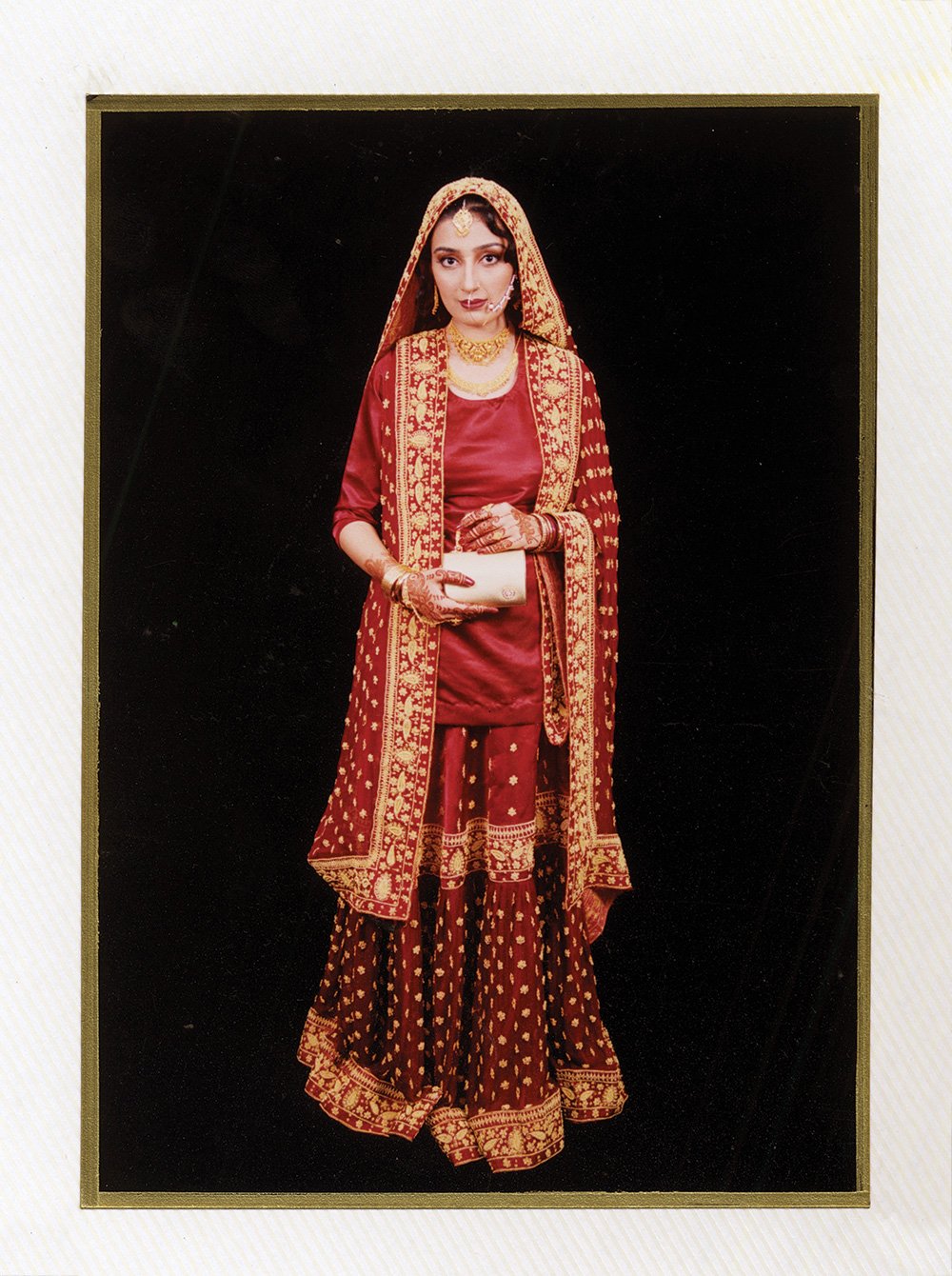

By 17, Zafar was married. Her official wedding was in Karachi, Pakistan, and afterwards, her husband went back to Canada to file the necessary paperwork while Zafar stayed behind. About a year later, he flew back again for a reception in Abu Dhabi.

By this time, Zafar had been married on paper for a year, but she barely knew her husband. They would speak on the phone occasionally and chat online, but he was still very much a stranger to her — a stranger who was 10 years older.

She moved to Canada within the week of her reception, and was pregnant within the month.

She was 18 and desperate to get her high school diploma.

At first, her husband was supportive of her finishing high school. A pregnant teen, she began taking courses through a local adult learning centre.

But when her in-laws came to Canada and they all moved into a house together, things took a turn. Zafar was no longer permitted to leave the house much on her own. Her husband became cold and the entire family looked down on her pursuing an education. The verbal abuse was steady, and the teenager was isolated.

Still, school kept her motivated.

Once her daughter was born, she continued school by taking correspondence classes. She’d receive her coursework by mail and work through her booklets in the evenings.

She remembers the person running the correspondence program told her that often the teens that took these courses were in prison.

“And I said, ‘Yeah, that’s kind of the case here, too,’” Zafar laughs.

When she finished high school, and was accepted into university, she was stuck. Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) wouldn’t give her a loan because her household’s recorded income was too high — but it was income she could not access. Her husband told her there was “no useless money” to give to her education.

“I was so heartbroken… I actually hung onto that acceptance letter from U of T for months, maybe even years, and would just look at it and cry,” she said.

By 2005, the abuse from her husband had escalated. The verbal abuse was constant, and it had become violent. She was miserable.

It was then that her father bought plane tickets for Zafar and her daughter to come back to the UAE to visit. Zafar said she felt like a happy high school kid again — as she walked through the airport, she removed her hijab and felt free.

Once in Abu Dhabi with her parents, she told her husband she wasn’t coming back — she was becoming her confident self again and had no plan to return.

But her husband and his family eventually convinced her father that she should come back. Her husband leased an apartment for just Zafar and the baby as a sort of peace offering and, while skeptical, she agreed to return, hoping that things would be better if it was just the three of them.

Upon her return, though, it was clear to her that things were not going to change. She planned to make money and return to Abu Dhabi for good.

She began tutoring kids in her apartment building, and babysitting here and there. Soon enough, she was able to purchase plane tickets to go to Abu Dhabi for her sister’s wedding — and this time, she was sure she wasn’t coming back.

But Zafar’s father passed away around this time, which complicated the situation for her and her family, as it left her mother to care for her unmarried sisters, and their finances had to be dealt with back in Pakistan.

“My husband came to Karachi, two days after my dad died, and the first thing he [did] was force me to have sex with him,” Zafar said.

At this point, the physical abuse in their relationship had reached new levels, and there were a couple particularly violent incidents in Pakistan. She remembers him slapping her across the face, pushing her to the ground, and kicking her in the stomach after he accused her of bending over purposely in front of her uncle (she had bent over to fix her shoes).

With her dad gone, and her mom “burdened” by two unmarried daughters, Zafar was forced to return to Canada and start over in a house with her abusive husband and his parents. And now, she was pregnant with her second daughter.

“But that time something had changed. Something had clicked in me,” she said.

She convinced her mother-in-law to help her start an at-home daycare and to take driving lessons with her, knowing the only way she’d get approval was to include her in all the planning. Zafar got her license and was allowed to get a van for the business.

She could finally afford to pay for school, so she started taking courses at the University of Toronto Mississauga. It was frowned upon in her household, but because she was bringing in money, the family seemed hesitant to cross her, she said.

Zafar was told not to engage or try to make friends. But after a teacher pointed her out in a class for having scored 100% on a test that had a class average of 40%, it was hard for her to not stand out, and people began to gravitate towards her.

Counselling and new friendships empowered Zafar. It wasn’t easy or immediate, but these relationships eventually gave her new strength. Her marriage reached its breaking point when one night her husband reached for her throat — that was it, Zafar left her husband.

By this point, she was attending school full-time and she was able to rent the last available on-campus house for her and her two little girls.

“It was so hard,” Zafar said, remembering working four on-campus jobs, as well as running a catering company out of her kitchen. “But it was just so awesome.”

Zafar lights up when she talks about friends crashing on a mattress in her living room, having movie nights or bringing her ice cream when she’d have bad days.

“I can’t tell you how many times I had the urge to go back, and they held me back,” she said.

In 2013, Zafar graduated top of her class at U of T in financial economics. At her graduation, she met a journalist who published a story about her in a Pakistani newspaper. She was flooded with messages of support and thanks from women in similar situations.

Since then, she has received her master’s degree in economics, written her own story for Toronto Life, and just became a bestselling author for her book A Good Wife, which was published earlier this month.

“What people need is friendship and connection and empathy and humanity, and I wanted to do more,” she said.

And so the idea behind her new project, called Brave Beginnings, was born.

Brave Beginnings is a platform that will connect mentors with abuse survivors, across a variety of industries. Zafar believes there is a good amount of crisis support available in Toronto — from police to counselling to shelters — but there could be more post-crisis support.

“During that first year or so, I wanted to go back all the time,” she said. “A lot of women go back or fall into the same pattern with another man.”

She hopes the relationships established through Brave Beginnings will help prevent that. The non-profit organization is not yet up and running, but the team is currently building the website, working to get charitable status, and recruiting mentors.

Zafar spends time engaging with people around the world. She speaks about her experience as a child bride, coping with abuse and the importance of connection and empowerment. She often speaks at universities, has given a TEDx Talk and serves on a number of boards, all with the goal of advocating for human rights.

Everything she speaks about always seems to come back to one clear point.

“The most important thing people need to succeed is human connection,” she said.

Global Citizens of Canada is a series that highlights Canadians who dedicate their lives to helping people outside Canadian borders. At a time when some world leaders are encouraging people to look inward, Global Citizen knows that only if we look outward, beyond ourselves, can we make the world a better place. In 2019, in honour of Global Citizen's #SheIsEqual campaign, this series will focus on gender equality champions across the country.