“How can I be a good ancestor?”

The question is just as important as the answer as it asks us to reexamine our relationship with the land we live on.

Access to land is essential for fulfilling a number of human rights, including the right to food, shelter, and participation in cultural life. Today, we celebrate peoples’ connection to the land not just as a tool for survival and personal enrichment, but also as a presence that shapes our relationships with one another, a trust in which we invest our hopes for future generations, and a home where we experience much of what it means to be human.

The concept of the “land” as an entity plays a particularly important role among Indigenous communities. The land represents rootedness, and the choice to remain rooted in the face of adversity has historically been a form of cultural resistance.

This especially resonates today, as Indigenous communities are some of the staunchest defenders of wildlife. In fact, Indigenous people protect around 80% of global biodiversity at a time when industrial forces degrade land and marinescapes at unprecedented rates.

In addition to concrete traditions of conservation, Indigenous communities are also protecting land through advocacy, by calling on world leaders to live up to the goals of the Paris climate agreement.

Connection to land spans generations and does not require being there physically. All too often, when communities have been uprooted, the concept of the homeland exists in theory, through stories and memories, and it remains a strong marker of identity.

To reflect on the histories and stories of land, we’ve curated a list of 11 books and movies that tell stories of community relationships with the land — all accounts of gratitude, liberation, and resilience.

1. As Long As Grass Grows by Dina Gilio-Whitaker

By opening her book with an exploration of the water protectors at Standing Rock, Gilio-Whitaker puts Indigenous people at the center of ongoing conversation about environmental justice and conservation, connecting the dots between access to land, food systems, environmental and nutritional health, and political participation. Eradication of Indigenous lives and culture by the American government and settlers was made possible in large part by the degradation, control, and perversion of the natural environment and traditional food systems, resulting in starvation and generational health consequences.

From the calculated extermination of the buffalo to the damming and incising of rivers, settlers’ subjugation of the land destroyed local ecosystems, inflicting direct consequences on nutrition and health. Forced resettlement as well as life on reservations severely limited Indigenous peoples’ access to traditional foods, forcing the substitution of diets rich in nutritional diversity for western-style staples heavy in fats and starches.

Gilio-Whitaker spotlights modern-day leaders in the movement to resurrect traditional food systems, quoting in one chapter Valerie Segrest, a member of the Muckleshoot Food Sovereignty Project, who explains: “At the core of tribal sovereignty is food sovereignty. This is significant because we know that our traditional foods are a pillar of our culture, and that they feed much more than our bodies; they feed our spirits.”

2. Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Kimmerer, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a botanist by profession, marries the interrogative process of the scientific method and its tools with the sense of discovery and appreciation that is the birthright of traditional ways of knowing.

She writes about the relationships that exist between land, its abundant gifts, and the people who live on it, and how we must mend this relationship if we are to solve the challenges of climate change today. A memoir of not just Kimmerer’s life but also the lives connected to hers across time, Braiding Sweetgrass recounts an array of anecdotes that include sugaring maple trees with her daughters; her grandfather’s reliance on abundant harvests of pigan (pecans); and her foray into botany to discovery why goldenrod and aster look so breathtaking when grown together.

Kimmerer rejects an imagined separation between the scientific and the spiritual. Her writing and her career are both a testament to the elegance and truth that emerges when we embrace traditional knowledge and lessons from the natural world.

3. The Land of Sad Oranges by Ghassan Kanafani

Palestine Poster Project Archives

Palestine Poster Project Archives

As one of the most well-known Palestinian authors, Ghassan Kanafani’s writing often invokes land and nature to tell the story of Palestinian exile. His short tale, Land of the Sad Oranges, explores the plight of one Palestinian family after Israeli forces took over the country in 1948, yet is in fact exemplary of the experiences of thousands of displaced families.

The titular oranges refer to the “Jaffa oranges,” which were cultivated by Palestinian farmers from the mid-19th century and take their name from the port city of Jaffa. Throughout the story, oranges are used as a metaphor for loss and for land — they symbolize all that exiled Palestinians must leave behind, and serve as a stark symbol of the intimate relationship between people and their land.

Leaving the land of the oranges equates to becoming a refugee, and with this comes the dilemma of finding shelter and food, showing the link between political problems and their socioeconomic repercussions. After Palestinians were forced out, the orange trees of Jaffa shriveled and died; just as people suffer when away from their land, so, too, does the land suffer.

4. Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice

As an Anishinaabe journalist, Rice grounds the fictitious community of Moon of the Crusted Snow in the true-to-life cultural practices, dynamics, and struggles of Canada’s First Nations peoples. When the boreal community is cut off from the energy grid during a brutal, deadly winter, the Anishnaabe band must come together and rely on its traditional knowledge to survive.

This story is about the generational traumas that enervate a community’s trust as well as the periods of attempted erasure and rebirth that are core to First Nations’ histories.

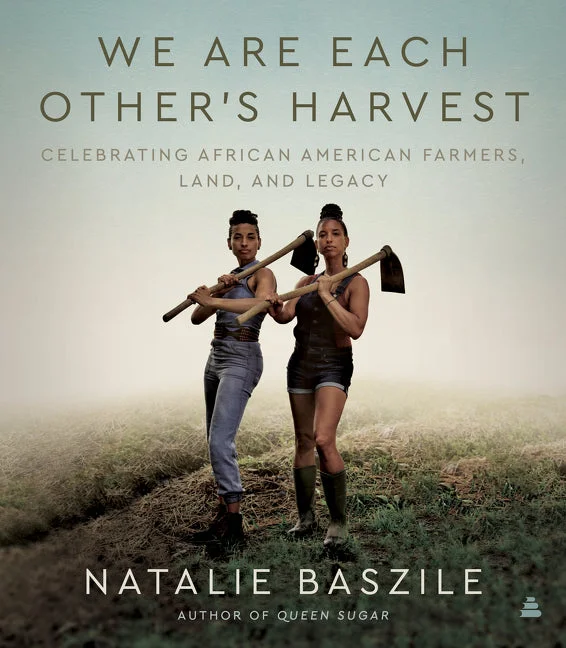

5. We Are Each Other’s Harvest by Natalie Baszile

Harper Collins Publishers

Harper Collins Publishers

One hundred years ago, there were over 1 million Black farmers in the US; today, only 45,000 remain. Less than half a percent of farm sales come from Black farmers. Systemic barriers and racial discrimination have created a crisis for Black land owners and farmers, which today is reflected in grocery stores and "food deserts" across the country.

Baszile tells the story of the “returning generation” of Black farmers and farmers of color who strive to reclaim the legacy of land stewardship, agriculture, and food sovereignty. “Black people’s labor and knowledge of agriculture built this country," she writes. "Farming is part of our national identity; it is central to America’s origin.”

This book is an anthology of lived experiences that honors the founders of the community-supported agriculture movement, the Black farmers of now and yesterday, and is rooted in the understanding that food sovereignty and justice are essential to building local, resilient food systems.

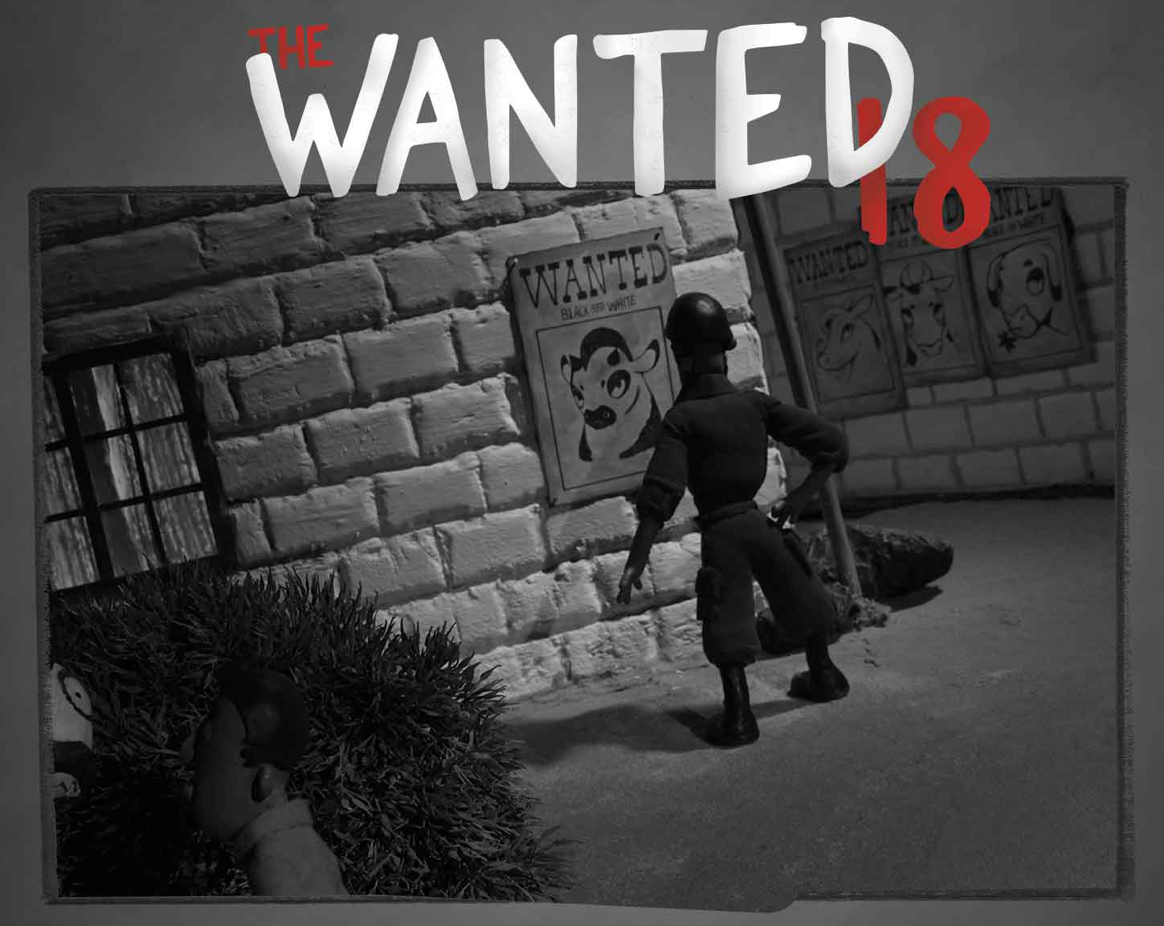

6. The Wanted 18

An animated documentary, The Wanted 18 tells the story of the Israeli army’s pursuit of 18 dairy cows. Against the backdrop of the First Intifada, a group of Palestinians try to start a small local dairy industry to produce milk for the town’s residents, so as to present a model of self-reliance and provide an alternative to Israeli goods. This causes issues with the Israeli army, who perceive the cows as a threat to Israel’s national security, and begin a hunt to catch them.

Palestine is traditionally a sheep-raising (not bovine) culture, and yet this documentary shows how the dairy collective became a symbol of nonviolent civil disobedience, and ultimately is about the fundamental human right to produce our own food.

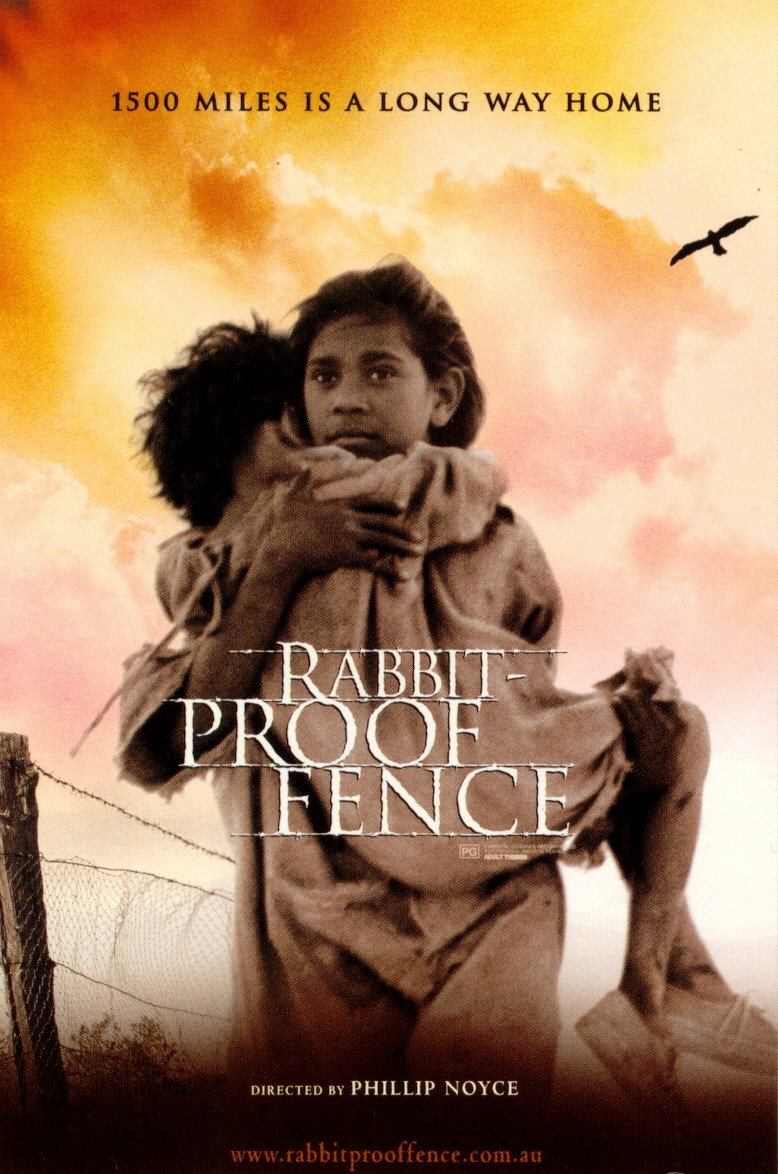

7. Rabbit-Proof Fence

Based on the 1996 novel by Doris (Nugi) Pilkington Garimara (Martu First Nations), Rabbit-Proof Fence tell the story of three young girls’ (including the author’s mother and aunt) internment and escape from the Moore River Native Settlement, and their 990-mile trek through the Australian outback to their homes in Jigalong, Western Australia.

The state-sanctioned kidnapping and subsequent escape of these girls takes place in the larger context of the Stolen Generation, a grim chapter in Australia’s history when mixed-race and Aboriginal children were removed from their families as part of a forced assimilation campaign. Garimara, who herself was taken from her family and brought to Moore River, has written about her relationship with her Aborginal heritage and connection to traditional lands in Caprice, A Stockman’s Daughter and spent much of her life working with Australia’s Reconciliation Council.

8. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa

Through writings about her identity — a queer, Mexican, American, and Indigenous woman — Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza examines her own relationship to land within the concept of the border — in this case, that which separates Mexico from the United States. Anzaldúa’s borderland is not merely a physical border, but also one that is psychological, sexual, and spiritual, and defines her very identity.

Geopolitics reinforce the view that one side of these borderlanders is seen as “wrong,” and the other is “normal.” Our relationship with land is often complicated and fraught with tension. Anzaldúa calls this experience of having a foot in two worlds the "nepantla," a liminal in-between that exists as a state of displacement, but becomes home over time. Through a mixture of prose and poetry, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza explores the concept of land as it is influenced by gender, identity, race, and colonialism.

9. The Worlds of a Masaai Warrior by Tepilit Ole Saitoti

In The Worlds of a Maasai Warrior, Saitoti offers an autobiographical account of his life growing up as a member of the Maasai community, a people whose traditions and livelihoods center around cattle-herding and are Indigenous to Tanzania and Kenya. Like many Indigenous societies, the Maasai lost a significant portion of their lands due to British colonialism as well as conservation efforts which appropriated traditional lands for the creation of national parks and safaris — legal battles over ongoing land disputes still persist today.

In his memoir, Saitoti reflects on his time as a ranger at the Serengeti National Park, his initiation into Maasai cultural life and their traditions, and his experiences living between the worlds of East Africa and the United States, where he completed his graduate studies. In a time when the Maasai people attracted international curiosity, Saitoti’s work ensured that the Massai remained narrators of their own stories. You can listen to one of Saitoti’s lectures on Maasai culture here.

10. Endings by Abd Al-Rahman Munif

Set in an Arabic desert village struck by drought, Abd Al-Rahman Munif’s Endings explores the relationship between man and nature, as told through the voice of a storyteller farmer. The interactions between the different societies represented in the story accentuate the main thread of the novel — that is, the danger of destroying nature in favor of an industrial society.

In the novel, the townsfolk of al-Tiba represent the tribal society who thrive off their connection with nature, while the guests of the town symbolize the new urban population, which has abandoned its appreciation for nature. Despite the harsh conditions of the desert, which seem to represent some sort of hell in the author’s descriptions, the people of Al-Tiba continue to live there, and bear an almost masochistic relationship with nature and the desert in which their village is situated. Ultimately, this story encourages readers to appreciate life and the fragility of the relationship between humans and nature.

11. Gold Dust by Ibrahim Al-Koni

Told against the backdrop of Italian colonialism, Ibrahim Al-Koni’s Gold Dust illustrates the relationship between man and beast in the rough Libyan desert. Ukhayyad, the protagonist, and his beloved mahri (an ancient breed of camel) are connected not only physically, but also spiritually, as the two beings seem to see themselves reflected in one another.

The novel follows the two beasts, and in a time where the country’s entire political structure is changing, and where the desert is man’s harshest obstacle, Ukhayyad and his camel endure the struggles of their partnership and, ultimately, find solace in their companionship.