"Forget that my net worth / Is hardly worth mentioning, / Forget the President’s name, / Forget Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, ”

“Forget politics. / Yes, yes, I’ve already forgotten. / Forgotten everything! / Have I got democracy now?”

Burmese poet Khin Aung Aye freely recites his poem in a cafe in Myanmar, a seemingly innocuous act that only a few years ago might have put him at risk of being arrested.

That he’s able to do so, and to be featured doing so in the internationally-screened documentary “Burma Storybook,” without fear of repercussion is a telling, albeit subtle, sign of change in Myanmar.

Less than seven years out from decades of military rule, Myanmar — formerly Burma — is finding its footing as a democratic nation. And its poets, whose art form was tightly intertwined with politics during the military regime, are re-examining their roles in society.

Through violent ethnic conflicts, a nationwide fight over how democracy should be implemented, and other political turmoil in recent months and years, poetry has steadfastly held a special place in Burmese culture. But as the country changes and evolves, its poetry is changing along with it.

That’s exactly what documentary-filmmakers Petr Lom and Corinne van Egeraat hoped to show with their film “Burma Storybook.”

“Burma Storybook,” available to watch on Vimeo, centers on Maung Aung Pwint, Myanmar’s most famous living dissident poet — who spent years as a political prisoner as a result of his poetry and activism — and paints a portrait of a country and people emerging from under decades of military control.

Take Action: Tell Congress not to slash foreign aid!

The film also features several other influential Burmese poets, including Khin Aung Aye, as they share their work and discuss the changing role of their art form in today’s Myanmar.

In Myanmar, poetry is universally admired. Many people are amateur poets, writing poetry in their free time and even using Facebook as a platform to publish, and professional poets are highly regarded and still hold an important role in society, Lom told Global Citizen.

“Poetry is extraordinarily widespread in Myanmar and very related to politics. Many prominent poets were also political dissidents when the country was under military control,” Lom said

Poet Maung Aung Pwint and his wife Daw Nan Nyunt Shwe.

Poet Maung Aung Pwint and his wife Daw Nan Nyunt Shwe.

Poet Maung Aung Pwint and his wife Daw Nan Nyunt Shwe.

Throughout the military regime, poets wrote about oppression and freedom, about resilience and “mother” — a code word for Aung San Suu Kyi who was then the head of the country’s pro-democracy movement and is currently Myanmar’s de facto leader. Their art served as a form of political dissidence that led many poets to be imprisoned.

“But you should never tell a good poet in Burma that they are a political poet,” he cautioned. “They’ll say ‘No! I don’t write about politics’ because in their context, they think that sounds like propaganda or bad art.”

“The military government made young people indifferent to politics. Most of my friends are still not interested in politics at all,” poet Mae Yway said in an interview featured in the film’s complementary book, also called “Burma Storybook.” “With the new democratic government, the word ‘politics’ has become popular, heard everywhere. Now some care about politics, some don’t. It’s a chaotic time,” she said.

Poet Mae Yway.

Poet Mae Yway.

Poet Mae Yway.

But it’s a time of change.

“Some poets say they feel much freer now and that they can write whatever they want,” Lom said. “But others say they are kind of at a loss. They're not sure what to write about anymore and they're not sure about their role in a democratic society.”

Where some poets had previously written about the country’s struggle for freedom, they are now exploring other subjects, ranging from discrimination against women and Myanmar’s budding democracy, to more quotidien themes of love.

Lom, who is based in the Netherlands, told Global Citizen that this shifting dynamic is precisely what made him interested in the country. A former academic with an interest in political theory, human rights, and injustices, Lom’s first experience in Myanmar was at a human rights film festival where he screened a prior documentary of his.

“At the time, Myanmar was this new, emerging country, and people there didn’t have a strong sense of human rights,” he said. “They just didn’t really know what they meant, but they were so keen and enthusiastic to learn about them."

He and van Egeraat knew they wanted to make a film about Myanmar and so they moved there and remained until 2015, leaving just after the country’s first democratic elections.

After the elections, the international community watched hopefully as Myanmar’s democratic transition seemed well underway. But in the years that have followed, the country has been criticized by organizations like the Committee to Protect Journalists and Human Rights Watch for its lack of press freedom and efforts to suppress the free flow of information.

Read more: Myanmar Blocks Investigators as Reports of Mass Grave in Rakhine State Emerge

While progress may seem slow from the outside, “Burma Storybook” reveals incremental gains in freedom of speech within the country. In fact, Lom said his film would have been impossible to make just a few years ago.

Filmmakers Petr Lom and Corinne van Egeraat.

Filmmakers Petr Lom and Corinne van Egeraat.

Filmmakers Petr Lom and Corinne van Egeraat.

“People coming here now often don’t realize that five or six years ago, these poets couldn’t have been seen talking to a foreigner on the street, they would have been shadowed by the secret police and it would have put them in danger,” Lom said. “It’s an amazing transformation.”

That is especially true for Myanmar’s dissident poets.

“As long as you’re criticizing the past and not the present, the government feels it’s okay. So the poets in the film can be outspoken about the past” and are able to talk about their work openly without fear of being imprisoned, as some had been in the past, Lom said.

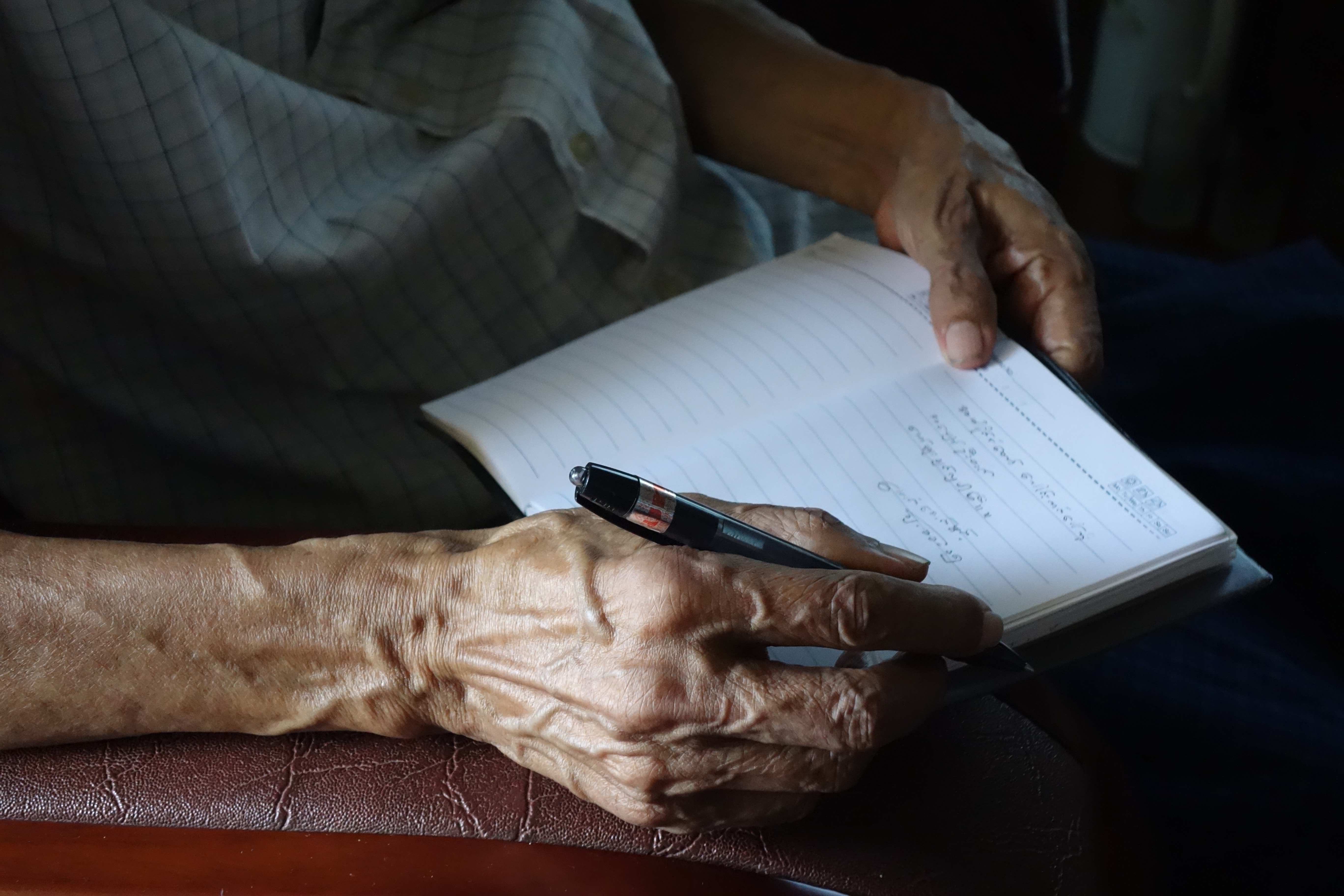

Hands of Maung Aung Pwint, dissident poet.

Hands of Maung Aung Pwint, dissident poet.

Hands of Maung Aung Pwint, dissident poet.

“There’s no longer really censorship for written speech in Myanmar, though films still get censored,” Lom said. “We had to go through the censorship board and process in order to be able to show our film in Myanmar,” he explained.

He added that this approval process is also part of the reason the film is not able to broach the conflict between Myanmar’s Rohingya ethnic minority and its military, which has recently garnered much international attention.

Until last fall, details of Myanmar’s national conflicts — and there are several ongoing conflicts — rarely made international headlines.

But last August, the Southeast Asian country began capturing international attention after its military began what it called a “counter-terrorism clearing operation” in northern Rakhine state, where most of its Rohingya people lived.

Between August and December, Myanmar and the plight of the Rohingya — 647,000 of whom fled to Bangladesh during that time — became a mainstay of international news outlets.

Read more: Timeline: How the Rohingya Crisis Unfolded in Myanmar

While Lom and van Egeraat left Myanmar in 2015, they returned several times in 2017, including late in the year after violence erupted in Rakhine state displacing hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people to Bangladesh. And though “Burma Storybook” does not feature Rohingya poets, Lom said the film and his work are not unaffected by the conflict.

“There has been this gigantic dark cloud over the country as the Rohingya crisis has been unfolding and that’s caused some people to feel disillusioned,” he said. “The army still has a huge role in how things are run and that has made people feel like they haven’t really transformed in any way or form. And that’s really worrisome for the future of the country and creates this sense that things are fragile.”

Discrimination against the Rohingya is widespread in Myanmar. But Lom told Global Citizen that as former political dissidents themselves, many Burmese artists and poets have a slightly different perspective on the crisis and are ashamed of the situation.

Still, while many of the poets Lom spoke with are sympathetic to the Rohingya’s struggles, “there are former dissidents who spent 20 years in jail who have been against Rohingya,” Lom said. “It’s confusing to me because it’s like being a human rights defender — but not equally for everybody.”

In a sense, the rift in opinions among members of this community, one that is relatively progressive, are a reflection of where Myanmar is today — a fledgling democracy, a country working to re-establishing itself after decades of oppression and suffering.

“In many ways this is still a very young country just starting to experiment with different forms of freedom,” Lom said. “But that is why we came back here to screen ‘Burma Storybook.’ The film showcases people from this country talking about important issues and it was important to show that back here.”

Global Citizen campaigns for freedom, for justice, for all. You can take action here to support the protection of human rights for all.