Thanks to an out-of-the-blue phone call in 1995, photographer Keith Bernstein launched a 14-year project documenting the public and private life of one of the greatest statesmen the world has ever known.

Incredibly, many of the images he took of Nelson Mandela, before, during, and after his time as president of South Africa, have spent the best part of the past two decades stuck in a box at the bottom of a cupboard in Bernstein’s bedroom.

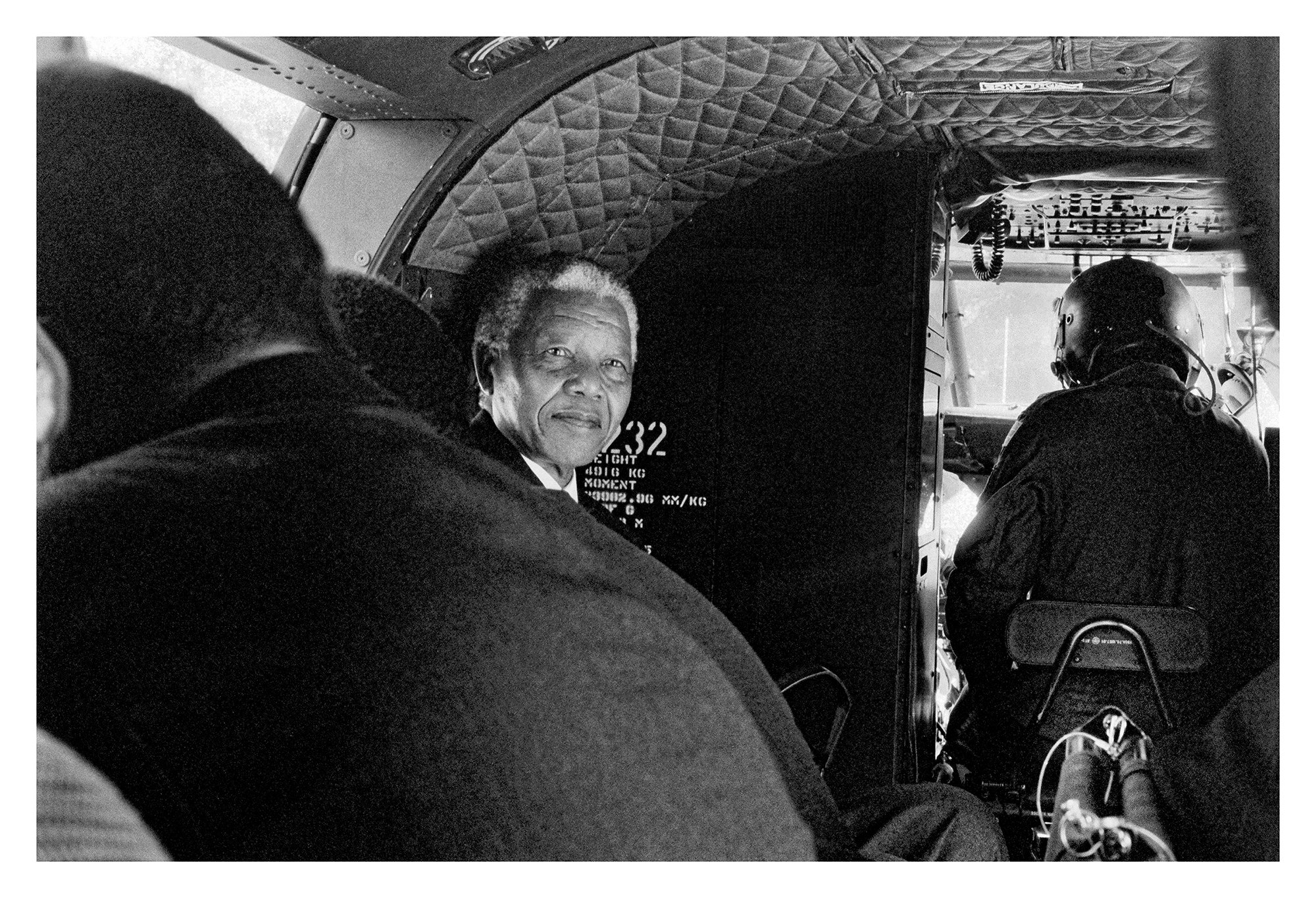

Mandela, 1995, pictured leaving Genadendal, the president's official residence in Cape Town, on his official helicopter.

Mandela, 1995, pictured leaving Genadendal, the president's official residence in Cape Town, on his official helicopter.

Mandela, 1995, pictured leaving Genadendal, the president's official residence in Cape Town, on his official helicopter.

But now, on the year that marks 100 years since Mandela’s birth, they have reemerged. And the passage of time has cast a whole new light on them for Bernstein.

“I’ve photographed lots and lots of famous people,” he tells Global Citizen, at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, where one of Bernstein’s photographs is currently being exhibited.

“I’ve photographed them and met them, and there really isn’t anybody that I look back on with that sense of unique privilege,” he says. “This period really sticks out for me and it grows as I get older.”

Now 61, Bernstein has been lucky enough to know Mandela at several points in his life. Bernstein was born in South Africa and spent his early childhood in the country. He is the son of Lionel and Hilda Bernstein, who both played a significant role in the struggle against apartheid.

Learn more: Global Citizen Festival: Mandela 100 on Dec. 2 in Johannesburg

“My father and my mother were close confidants of Mandela during the late '50s and early '60s in South Africa,” he says. “My dad was one of the accused at the Rivonia trial [in 1964], which was the trial that saw Mandela and others sent down to Robben Island. My dad was one of the ones who was acquitted, and he and my mother left very shortly afterwards.”

While Bernstein was just 6 years old when he family fled, he has returned to the country where he was born on numerous occasions — including to document Mandela’s journey to the presidency.

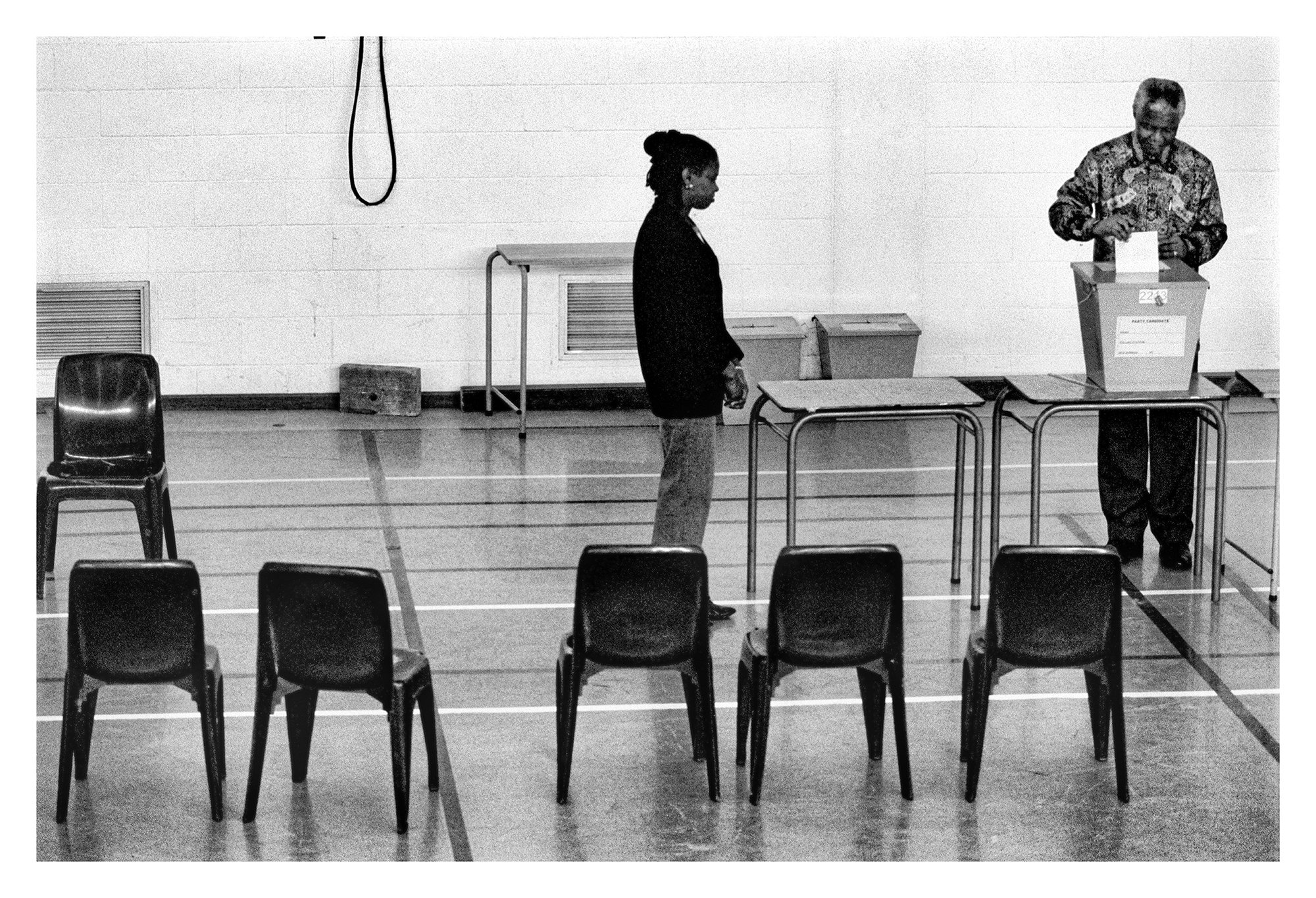

Mandela casting his vote in 1994.

Mandela casting his vote in 1994.

Mandela casting his vote in 1994.

“It was a really joyous and optimistic period, because they’d just come out of a whole stretch of decades and decades of apartheid,” he continues. “And this incredibly charismatic and magnetic leader had been elected and was somebody who was known around the world. Everybody, whether they were pop stars or actors or other leaders, they all wanted to meet him and be associated with him.

“So there was a feeling that it wasn’t just another election and another different person,” he says. “He was somebody kind of special, and he carried that aura with him very definitely wherever he went … It had that feeling of optimism, and rebirth, really.”

While he had slight “in” with Mandela, thanks to his parents’ relationship with the leader decades before, Bernstein points out that it was a very different time in terms of access to state leaders.

Take action: Be the Generation to End Extreme Poverty

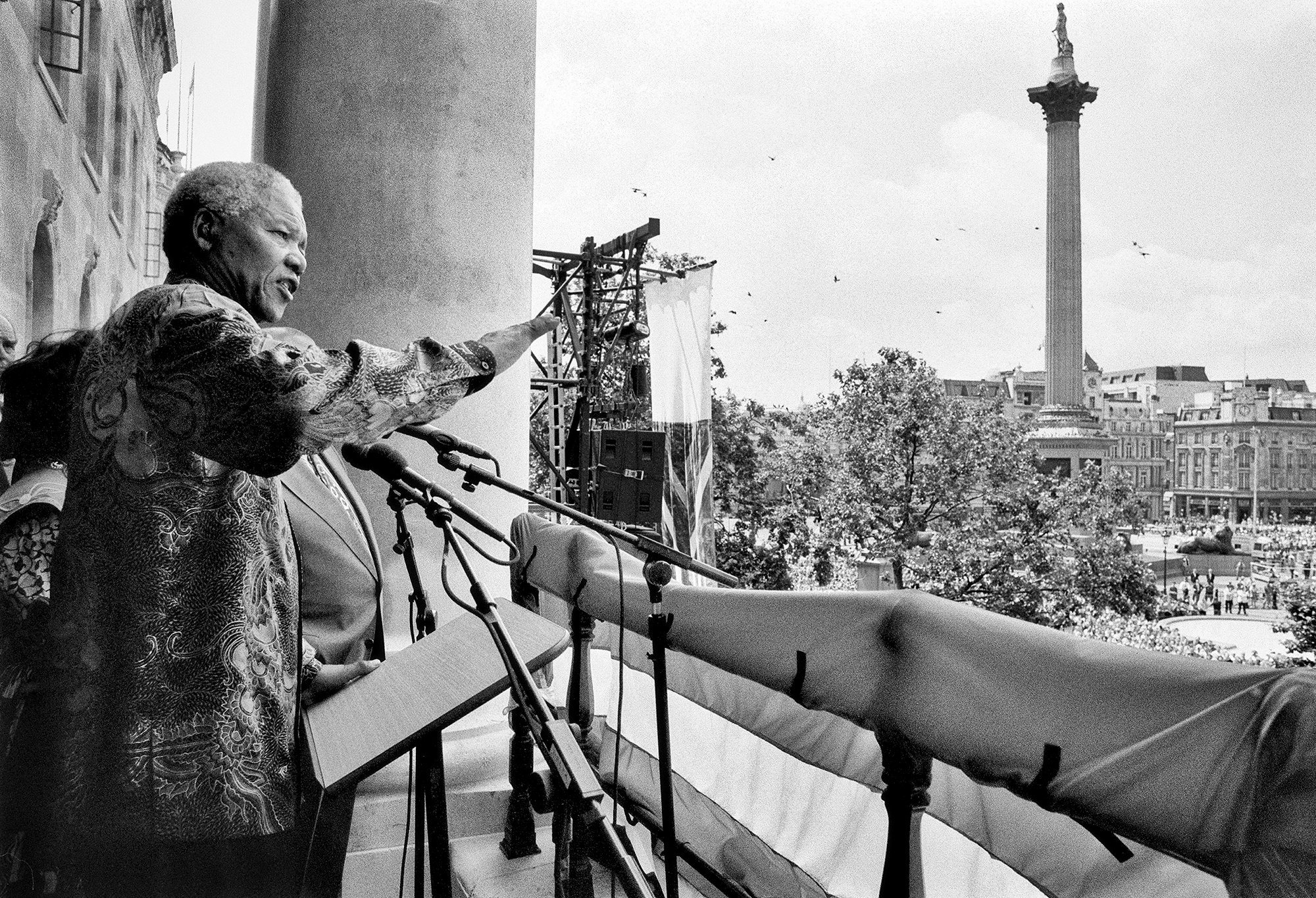

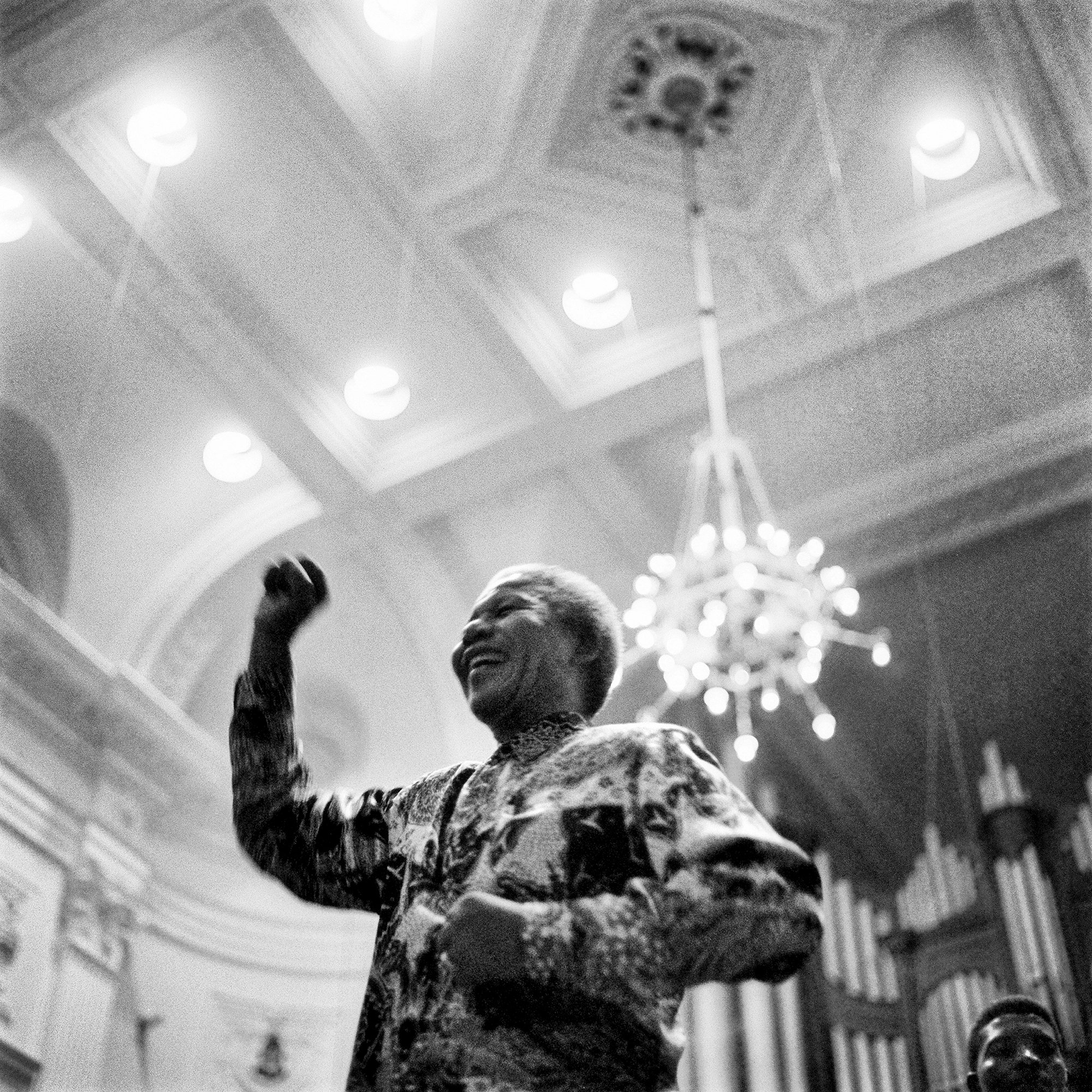

From the balcony of the High Commission of South Africa in Trafalgar Square, London, Mandela symbolically addresses the crowd gathered in 1996. Trafalgar Square was the site of continual demonstrations and pickets during the final years of apartheid.

From the balcony of the High Commission of South Africa in Trafalgar Square, London, Mandela symbolically addresses the crowd gathered in 1996. Trafalgar Square was the site of continual demonstrations and pickets during the final years of apartheid.

From the balcony of the High Commission of South Africa in Trafalgar Square, London, Mandela symbolically addresses the crowd gathered in 1996. Trafalgar Square was the site of continual demonstrations and pickets during the final years of apartheid.

“You just had incredible access just by hanging around for a while and being there for a period of time, you got to know his security guards, you got to know his press officers, you just had incredible access to him,” he says. “You would turn up at events and he’d just be, you know, as close as the next table is now.”

Less than a year after Mandela had been elected, Bernstein, who was by then back in London, got a unexpected phone call from Mandela’s long-time private secretary, Zelda La Grange, who invited him out to South Africa within the week.

“Without any kind of preparation or knowing what I was going out for, I just flew out to Cape Town,” he said. “I used to go to his official residence in Cape Town in the morning, without knowing what his programme was and just follow him for the day … I had no idea what the programme was each day, but I would just turn up at eight in the morning and was given unlimited access.”

“It’s just a perfect reflection of the time that it was,” he added.

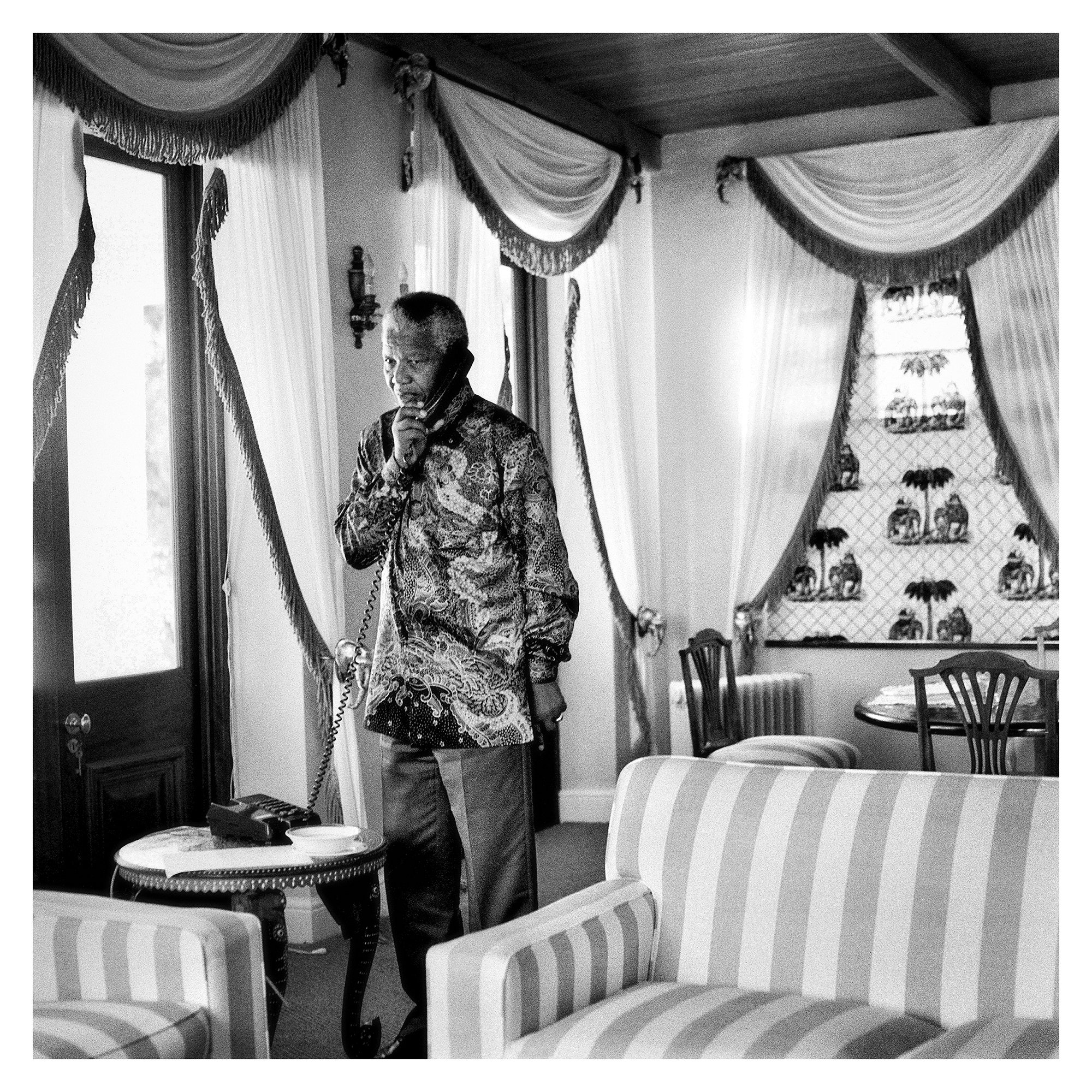

It was the beginning of what was to become a years-long project with extraordinary access to Mandela. At times, Bernstein was one of hundreds of international photographers clamouring to get a shot of Mandela at public events. On other occasions, he was alone with Mandela in the living room of Genadendal, the president's official residence in Cape Town.

Mandela in his private sitting room on the first floor of Genadendal, Cape Town in 1995.

Mandela in his private sitting room on the first floor of Genadendal, Cape Town in 1995.

Mandela in his private sitting room on the first floor of Genadendal, Cape Town in 1995.

And the time that Bernstein spent with Mandela, documenting how he spent his days as president both in public and at home, has left him with a sense of awe that will last a lifetime.

“He was everything that he appeared to be,” he continues. “He had an incredible presence when he came into a room. And I was with him when there have been other really, really famous people there as well and everybody was kind of … diminished by his presence.”

“I mean, he was physically big, as an ex-boxer … so he was physically imposing, but he also had, I guess it’s tied up with the myth of him, but he just had an incredible presence,” Bernstein adds. “When he walked in, rooms went quiet and people were always respectful of him, always. So there was always kind of a hush about him.”

Mandela in 1994, pre-election, campaigning in Elim, Overberg.

Mandela in 1994, pre-election, campaigning in Elim, Overberg.

Mandela in 1994, pre-election, campaigning in Elim, Overberg.

“And he could be very funny and very spontaneous, and he would do things that detached him from any other politician,” he says. “He had the ability to do things spontaneously and make it look absolutely real.”

One particular memory that stands out for Bernstein is when he went with Mandela to the township of Soweto, in Gauteng province, where Mandela was giving a speech in a “very run-down hall.”

“It was packed,” remembers Bernstein. “And he was on the stage with a few other dignitaries and other local representatives, and it was a really hot day and he was in a suit. White shirt, suit, and tie."

Just before Mandela started his speech, however, somebody said they had presentation for him. A child came up to him clutching a football shirt, the kit of the local football team, with Mandela’s name on the back.

“Without even missing a beat or thinking about it he just took off his jacket and he pulled the football shirt on, so he had the white shirt sticking out underneath, and he just stood up and did he speech,” says Bernstein. “And I just kind of thought, he just did it so easily and naturally and he looked completely like the president when he was giving the speech, even though he was wearing this football shirt he’d just been given.”

“He just had that way,” he says.

Looking at Bernstein’s images from that time, the sense of chaos, crush, and movement that always surrounded Mandela throughout his years as president is so clear.

Everywhere Mandela went, according to Bernstein, there were crowds, and people wanting to stop him and talk to him. And it was easy for . them to reach him, because Mandela didn’t want a “cordon of steel” around him. But Mandela “would just speak to them as if he was a normal person.”

“Everywhere he went there was kind of a pop star mania and he was just thronged by people,” says Bernstein. “You just didn’t see him, unless he was at home in his own private room, you didn’t see him alone.”

But it was while on the back porch of Mandela’s home that Bernstein witnessed one of his favourite examples of the leader, relaxed, showing his sense of humour — and it, somewhat unexpectedly, involves the Spice Girls.

“As I said, every famous figure in the world wanted to be photographed with him, or aligned with him, and often this stuff was arranged and he’d be brought out for a photo call,” he remembers. “The Spice Girls were on tour and they came to South Africa and they were photographed for about two minutes with him in the middle."

“About a week later,” he continues, “a journalist said to him, what was it like meeting the Spice Girls? And he never answered anything immediately — he always had a slow, pedantic way of speaking, and he’d always wait and he’d think about the answer. And he just looked down and the press were all waiting and the room was silent, and he said, 'It was the greatest moment of my life.'”

Nelson Mandela.

Nelson Mandela.

Nelson Mandela.

The last time that Bernstein met Mandela, and took his photograph one final time in 2009 in Cape Town, the former leader was in his 90s, he was getting older, and his hearing and his memory were failing. But, for Bernstein, he was still the same physically imposing character he had always been.

“I don’t know whether that is part of people’s perception of him,” he adds. “You’re aware he’s an iconic figure and therefore he brings some aura and history with him. But even when I photographed him when his memory was poor, and his hearing was poor, he was still a kind of giant.”

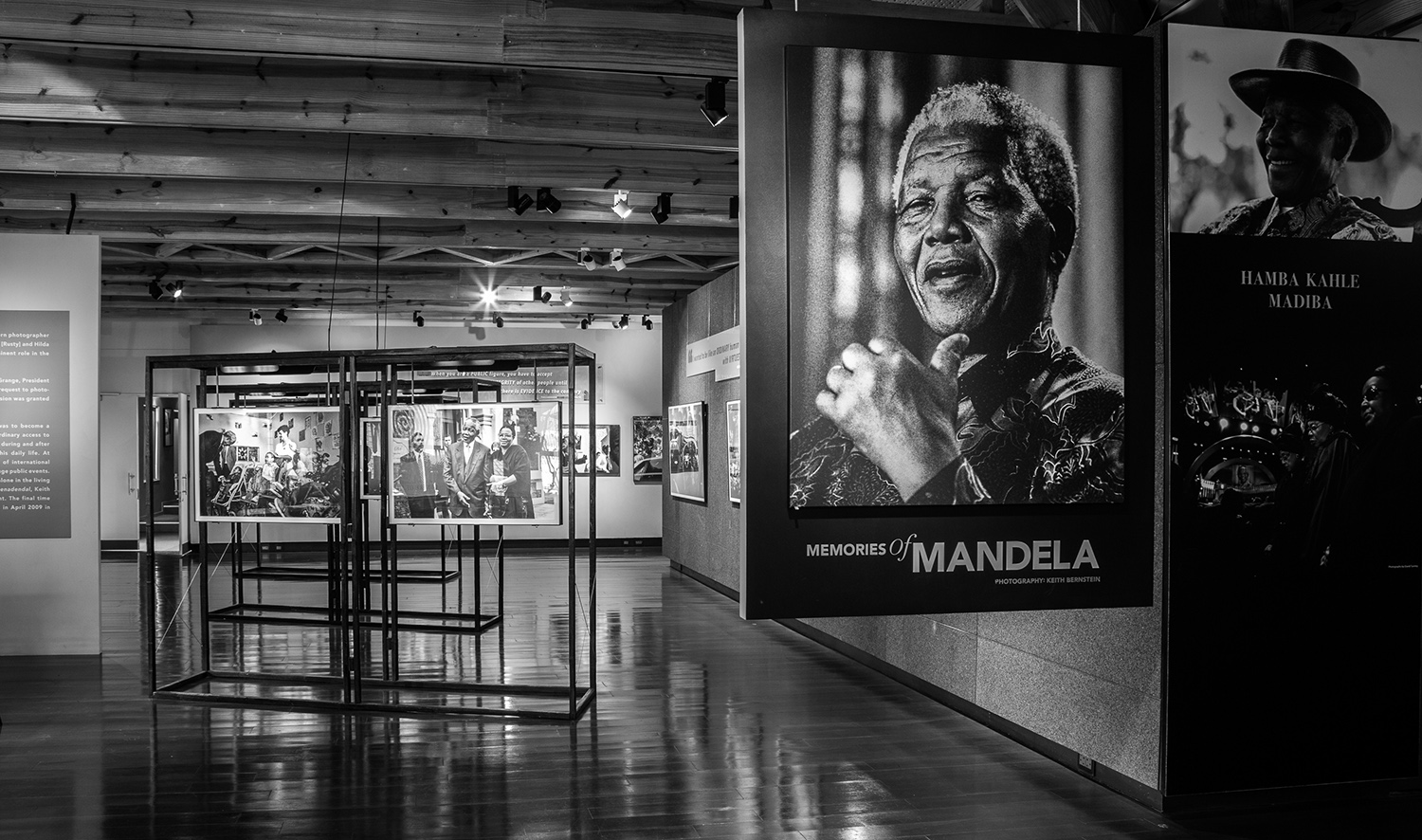

- A selection of Keith Bernstein’s photographs of Nelson Mandela were gathered together by curators the Photographic Archival Preservation Association (PAPA), for a special centenary exhibition, to honour and celebrate the life of the leader in the year that marks 100 years since his birth.

The Global Citizen Festival: Mandela 100 is presented and hosted by The Motsepe Foundation, with major partners House of Mandela, Johnson & Johnson, Cisco, Nedbank, Vodacom, Coca Cola Africa, Big Concerts, BMGF Goalkeepers, Eldridge Industries, and associate partners HP and Microsoft.