After crunching the numbers and weighing the costs, scientists have found the optimal diet for humans and the planet, and they’re calling it the “planetary health diet,” according to the Guardian.

The diet calls for nothing less than the overhaul of agricultural and food systems. If the diet is broadly adopted, the scientists claim, the future health of the planet, and people everywhere, could dramatically improve.

Failing to enact these reforms, however, would lead to catastrophe.

“The planetary health diet is based on really hard epidemiological evidence, where researchers followed large cohorts of people for decades,” said Marco Springmann, food and climate expert at Oxford University and part of the commission. “It so happens that if you put all that evidence together you get a diet that looks similar to some of the healthiest diets that exist in the real world.”

Take Action: Demand Food: Ensure No Child is Imprisoned by Malnutrition

Thirty scientists were gathered over the past year for the Eat-Lancet Commission on food, planet, and health, which started by asking if the planet could support 10 billion people by 2050, and found that current eating habits and agricultural practices make that prospect exceedingly difficult to realize.

Even for current population levels, the report argues, the global food system is broken and poses a dire threat to the planet.

“While global food production of calories has generally kept pace with population growth, more than 820 million people still lack sufficient food, and many more consume either low-quality diets or too much food,” the report says. “Unhealthy diets now pose a greater risk to morbidity and mortality than unsafe sex, alcohol, drug and tobacco use combined.”

Read More: Poor Diets Are a Bigger Threat Than Deadly Viral Infections: UN

“Global food production threatens climate stability and ecosystem resilience and constitutes the single largest driver of environmental degradation and transgression of planetary boundaries,” the report continues. “Taken together the outcome is dire.”

The case for altering humanity’s relationship to food to protect the planet has been continually made over the past several years. For example, because the global production of red meat has led to widespread deforestation, diminishing water supplies, and greenhouse gas emissions, scientists have long called on people to vastly reduce their meat consumption.”

As a result, the Eat-Lancet Commission doesn’t make radically new dietary suggestions, it just backs up long-standing recommendations with extensive data and offers a roadmap for companies involved in food production and governments tasked with oversight.

Read More: Why You Should Probably Never Eat Red Meat Again

Not surprisingly, the report calls for the sharpest dietary changes in the United States and Europe.

US citizens, for example, need to reduce their red meat consumption by 84% on average to adhere to the diet, while eating six times more beans and lentils. In Europe, people need to reduce red meat intake by 77%, and eat 15 times more nuts and seeds.

While these may seem like massive shifts, they would bring these diets more in line with the global average.

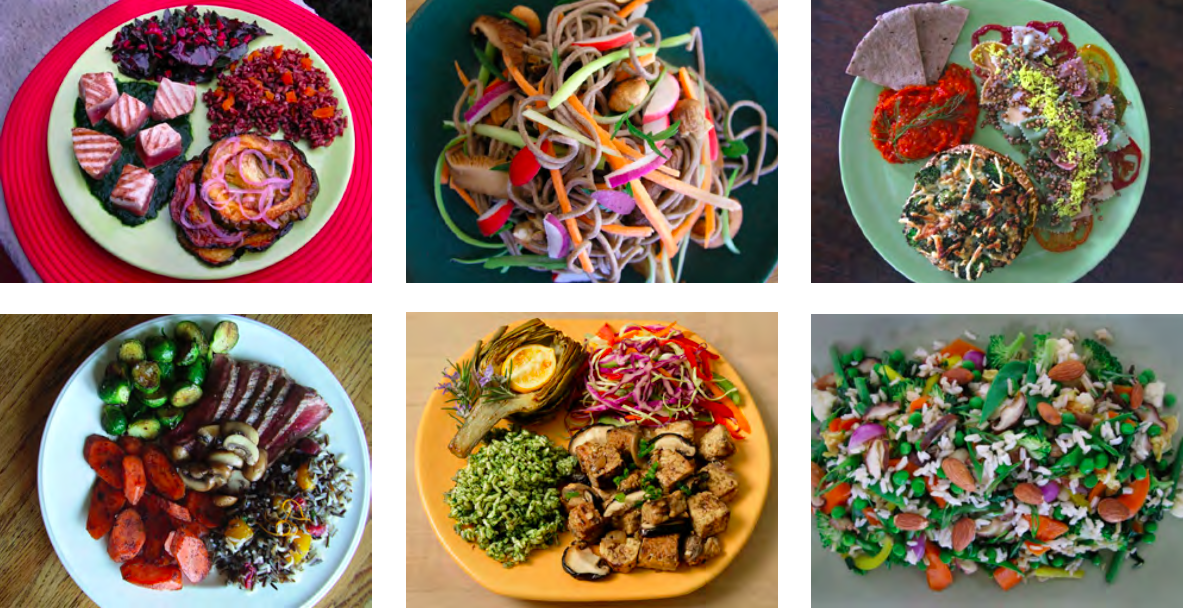

Overall, the planetary health diet involves 2,500 calories per day. People following the diet are asked to eat no more than one beef burger, two servings of fish, and one or two eggs per week. The vast majority of proteins will come from pulses and nuts, fruits and vegetables will account for around half of every plate of food consumed, and cereals will deliver a majority of calories.

Read More: Going Vegan Is 'Single Biggest Way' to Help Planet: Report

The authors stress that the diet allows for and even encourages great variety.

More importantly, however, the diet would make the most of the planet’s limited resources, while providing a balanced diet to 10 billion people.

The report is being released to policymakers in 40 cities around the world to build support and they expect to get generate significant interest.

“The planetary health diet is based on really hard epidemiological evidence, where researchers followed large cohorts of people for decades,” Marco Springmann of Oxford University who took part in the commission, told the Guardian. “It so happens that if you put all that evidence together you get a diet that looks similar to some of the healthiest diets that exist in the real world."