On June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood. At the time, homosexuality was illegal and cross-dressing was a crime. Police had the right to raid and close down bars if they had gay patrons, but that night the LGBTQ community decided to fight back.

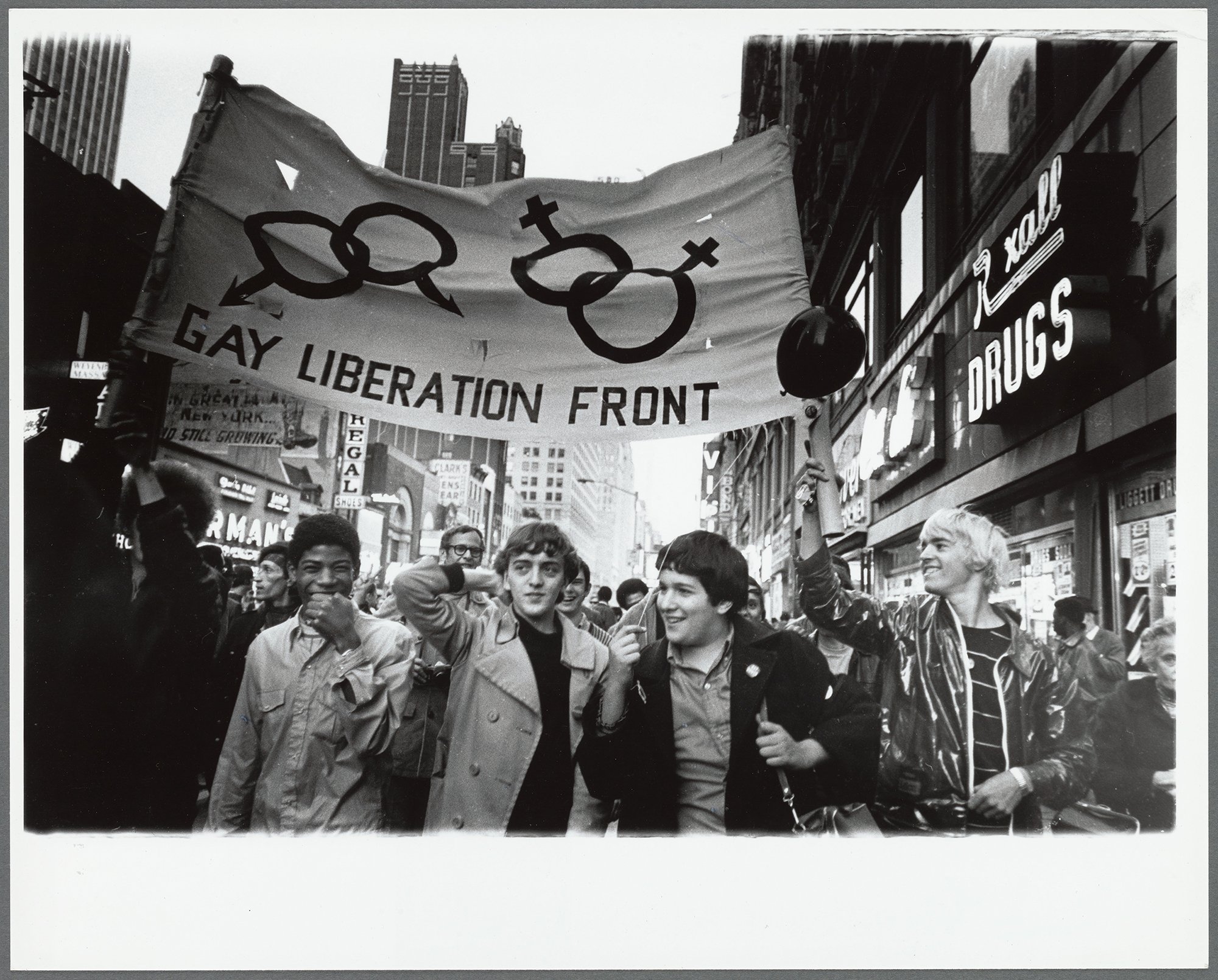

Demonstrations turned violent and continued for several days. A new community of LGBTQ activists stepped up and a number of groups formed the Gay Liberation Front as a result.

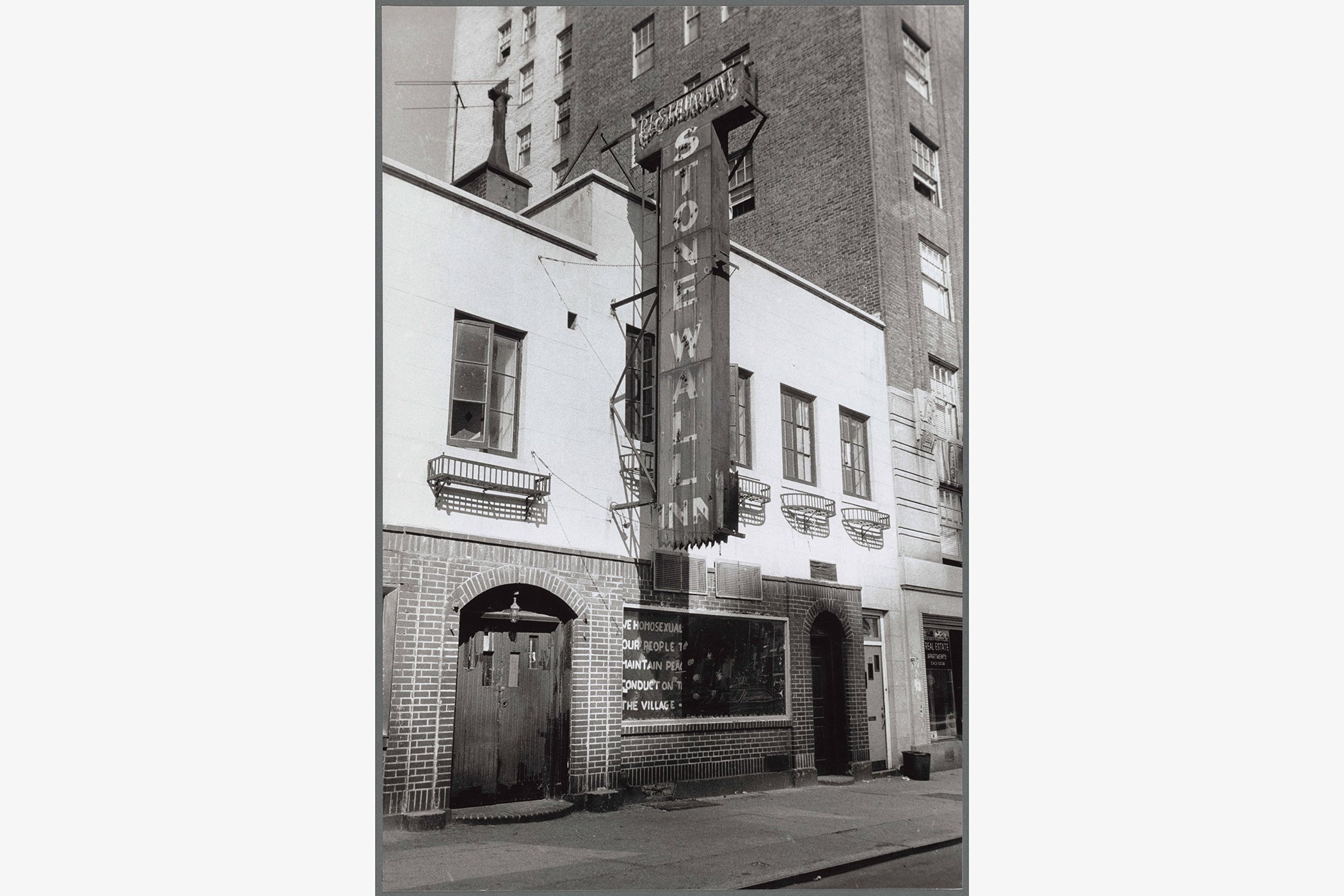

In June 1969, the Stonewall Inn was the site of famous riots that changed LGBTQ activism and American culture. Stonewall Inn is pictured here in 1969.

In June 1969, the Stonewall Inn was the site of famous riots that changed LGBTQ activism and American culture. Stonewall Inn is pictured here in 1969.

In June 1969, the Stonewall Inn was the site of famous riots that changed LGBTQ activism and American culture. Stonewall Inn is pictured here in 1969.

The exhibition “Love and Resistance: Stonewall50,”hosted by the New York Public Library (NYPL), which opened on Valentine’s Day 2019 in New York City, is on view through July 13. The exhibition draws from the library’s robust collection of artifacts reflecting LGBTQ history to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the riots, which are considered a major turning point in the international LGBTQ rights movement. Broken up into four parts — resistance, bars, in print, love — the exhibition includes photographs, posters, and original documents that capture the historic moments that shifted the conversation around LGBTQ rights and the decades of activism that followed.

Jason Bauman, who curated the exhibition and edited an accompanying book of the same name, told Global Citizen that the display is an important way to help the LGBTQ community see themselves reflected in history.

“You get this narrative of LGBTQ movements … First there was Stonewall, then there was AIDS and everybody felt bad for gay people, and then there was gay marriage. [But] in between there’s actually all of this political activism that takes place,” Bauman said of his motivation for curating the show.

After Stonewall, members of the anti-war student movement, civil rights movement, and black power movement brought a new perspective to LGTBQ activism. DIY newspapers and magazines, which are on display in the exhibition, helped spread the movement throughout the world. Bauman hopes that the exhibition serves as a reminder of the many issues that still need to be addressed to ensure that LGBTQ people are equal, from discrimination in employment to voting rights.

“All of this material from the ‘70s deserves a fresh look to see how it can inspire people today,” Bauman said. “Intersectionally isn’t new, that’s what emerged after Stonewall.”

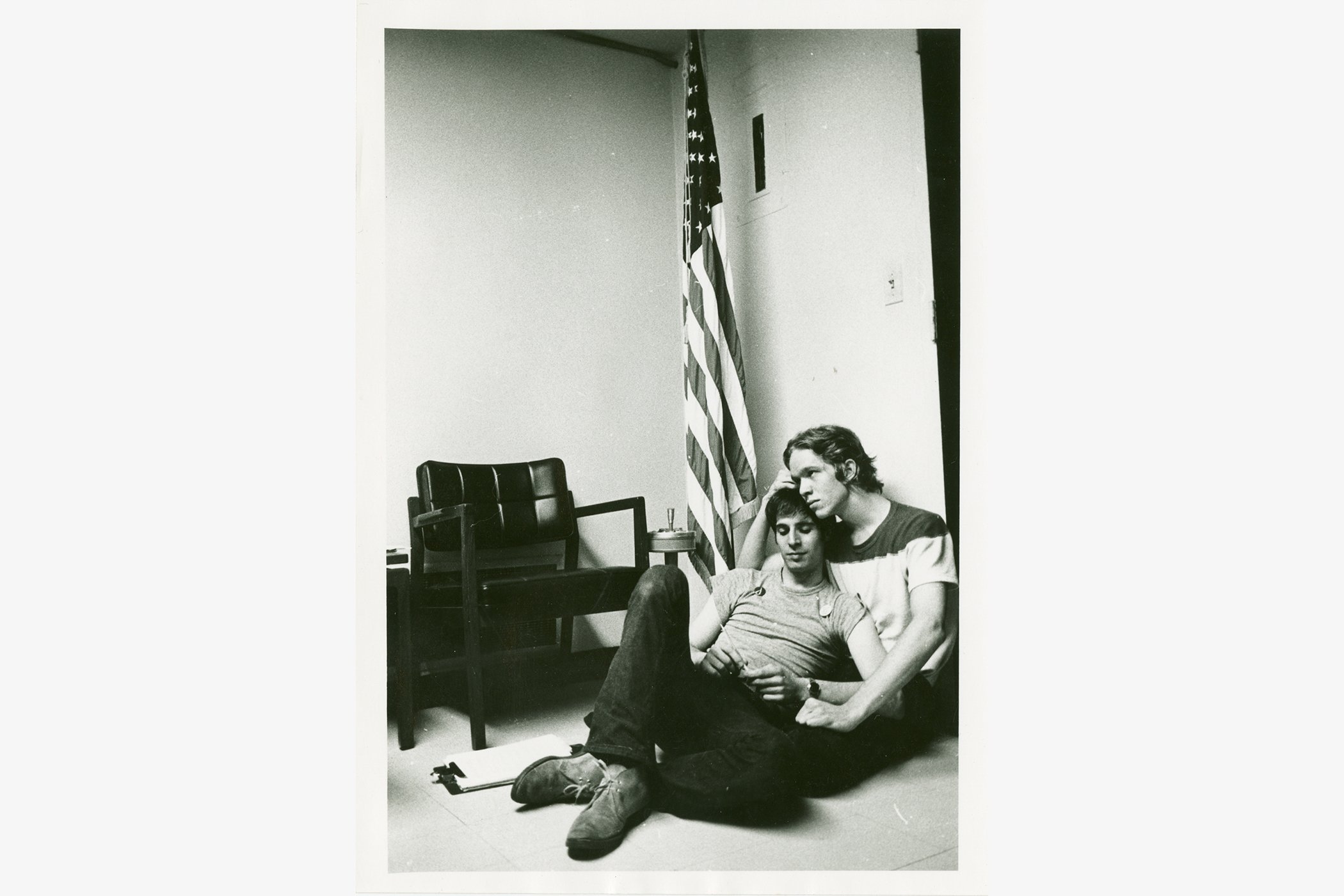

Marty Robinson and Tom Doerr are pictured during the Gay Activists Alliance's sit-in at the Republican State Committee on June 24, 1970, which requested that New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller address the demands of the gay community.

Marty Robinson and Tom Doerr are pictured during the Gay Activists Alliance's sit-in at the Republican State Committee on June 24, 1970, which requested that New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller address the demands of the gay community.

Marty Robinson and Tom Doerr are pictured during the Gay Activists Alliance's sit-in at the Republican State Committee on June 24, 1970, which requested that New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller address the demands of the gay community.

Snapshots of protests highlight the organizations involved in the “homophile movement,” which demanded respect and equal rights for all people, regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation in the '50s and ‘60s. The movement emerged in response to McCarthyism — a campaign against alleged communists in the US government in the ‘40s and ‘50s — which kept LGTBQ people out of federal jobs and the military.

Baumann said it’s troubling to see the similarities between recent US policies barring trans people from military service and those from decades ago — despite how far LGTBQ rights have come since then.

In the 1960s and 1970s, LGBTQ organizations didn’t only congregate on picket lines and during sit-ins. “Stonewall 50” highlights the importance of dance parties and balls that were used as alternative spaces to the illegal gay bars that were subjected to harassment from law enforcement. The funds raised at these events also supported the movement.

As resistance groups grew in the wake of the Stonewall Riots, the nightlife scene played an increasingly critical role in the organizing process.

Crowds dance at the Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse in 1971.

Crowds dance at the Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse in 1971.

Crowds dance at the Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse in 1971.

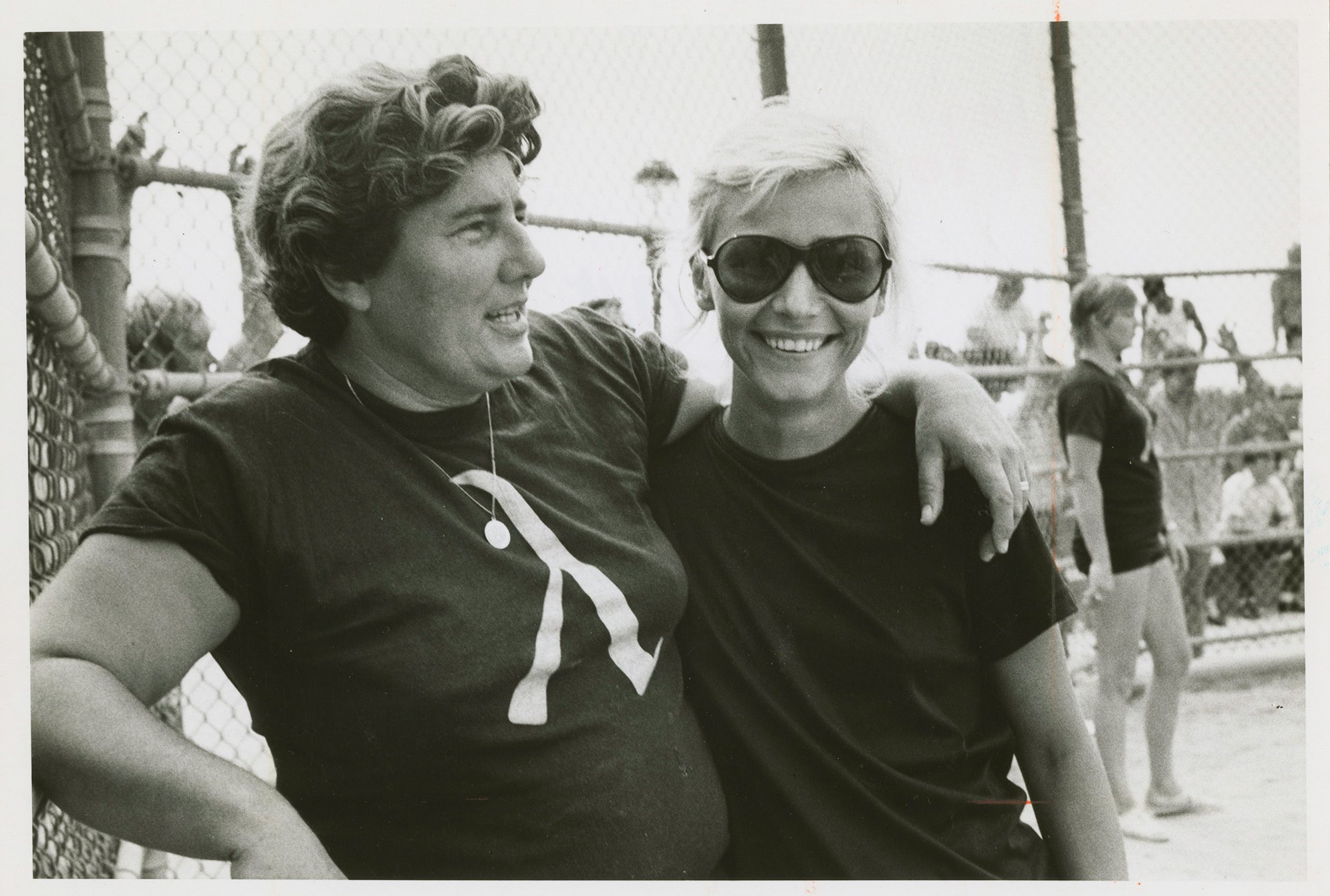

In addition to political demonstrations, the Gay Activists Alliance also sponsored social events, including a softball team, members of which are pictured here. The photograph ran in Gay magazine with the caption: “Is Shea Stadium Ready for Our Team?”

In addition to political demonstrations, the Gay Activists Alliance also sponsored social events, including a softball team, members of which are pictured here. The photograph ran in Gay magazine with the caption: “Is Shea Stadium Ready for Our Team?”

In addition to political demonstrations, the Gay Activists Alliance also sponsored social events, including a softball team, members of which are pictured here in 1970. The photograph ran in Gay magazine with the caption: “Is Shea Stadium Ready for Our Team?”

“Part of political activism involves creating a community,” Baumann explained. “That’s the thing that I’m always worried is missing, particularly with social media and the way people relate today.”

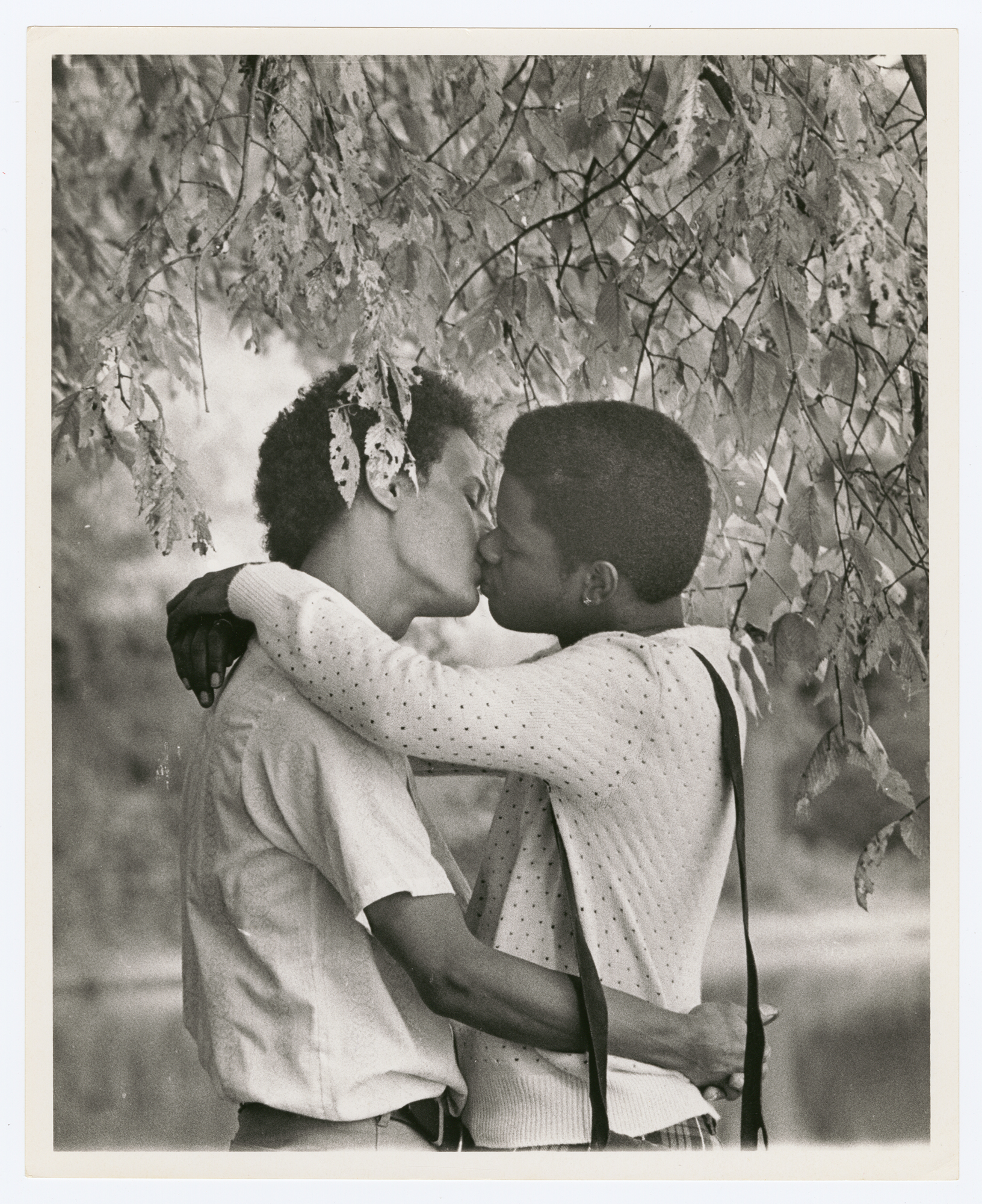

In putting together the exhibition, Baumann realized he couldn’t only include photos of angry protestors. In fact, the show doesn’t include many photos from the Stonewall Riots themselves because there actually weren’t many taken during the chaos. Baumann decided to include images that get at what the LGTBQ movement is, and has always been, fighting for: love.

For activists in the 1970s, open expressions of love and affection in their daily lives and at protests were brave political acts. “Stonewall 50” features intimate shots of couples taken by pioneering photojournalists Kay Tobin Lahusen and Diana Davies. Lahusen was known for photographing couples from behind to protect the identities of people who weren’t open about their same-sex relationships or feared for their safety.

By showing the full scope of the Stonewall Riots, Bauman hopes that the show inspires others to take a stand against the injustices still taking place today.

“I want people to know what it actually takes to make a difference in the world,” he said. “It isn’t that there was this riot and then the world changed.”

The Gay Liberation Front marches on Times Square in New York in 1970.

The Gay Liberation Front marches on Times Square in New York in 1970.

The Gay Liberation Front marches on Times Square in New York in 1970.