This post is part of a series produced by The Huffington Post, "What's Working: Sustainable Development Goals," in conjunction with the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The proposed set of milestones will be the subject of discussion at the UN General Assembly meeting on Sept. 25-27, 2015 in New York. The goals, which will replace the UN's Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015), cover 17 key areas of development -- including poverty, hunger, health, education, and gender equality, among many others. The What's Working SDG blog series will focus on one goal every weekday in September. This post addresses Goal 5.

When a girl doesn't show up for school here in Zimbabwe, there is no shoulder-shrugging among the "Mothers' Groups" formed to bridge the occasional divide between home and school life.

"Why is your 12-year-old daughter not in school?" one mother might ask of another. She may learn that the mother has taken a new job as a farm hand far away and needs her daughter to do chores at home. Or perhaps the family is ashamed to send their daughter to school without sanitary pads. Whatever the reason, the Mothers' Groups will help the family find a solution. Their system rests on a fundamental principle: accountability. And that accountability grows out of shared respect, trust and support among the mothers.

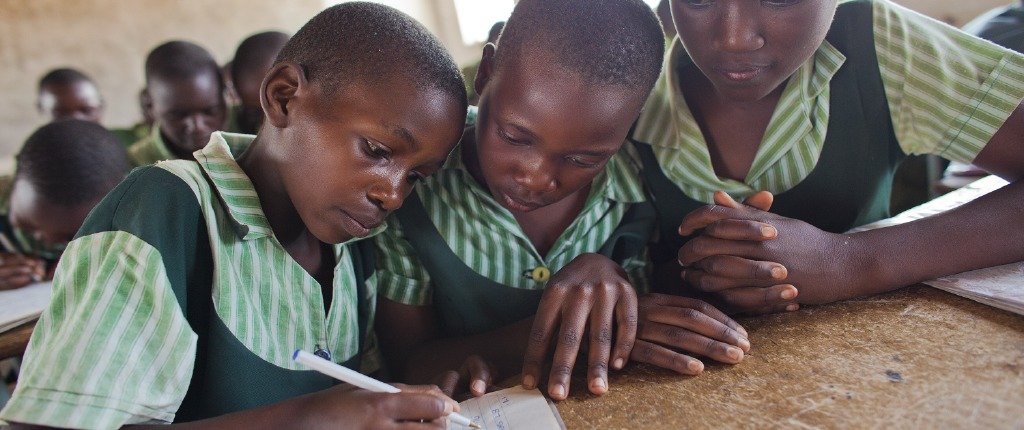

Based on shared trust and respect, Mothers' Groups in Zimbabwe support girls' education and value accountability as a necessary means of achieving their goals.

The nations of the world must create a system with that same kind of accountability when the UN General Assembly meets later this month in New York to ratify the Sustainable Development Goals, which lay out a path for ending global poverty, confronting climate change and closing equality gaps by 2030. Like the Mothers' Groups in Zimbabwe, countries must ask each other the hard questions as they fund, implement and measure the goals at the national level. Accountability is particularly critical in realizing the promise of Sustainable Development Goal 5, which calls for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Countries must challenge each other to track progress toward achieving the goals -- progress that in the case of Goal 5 will come by ending all forms of discrimination and violence against women and girls and by ensuring women's full participation in political, economic and public life. And when there are gaps or lack of progress, there must be a system forcing meaningful follow up to fix the problem.

Reaching many of the other 16 goals, after all, requires progress on gender equality. There are no safe and inclusive cities and human settlements (Goal 11) unless we prevent and eliminate violence against women and girls. There is no ending poverty in all its forms (Goal 1) unless growing numbers of women have land rights, access to financial services and are allowed their seat at the decision-making tables of their communities and households. It isn't possible to ensure healthy lives for all ages (Goal 3) as long as young girls are forced into marriage at a rate of one more every two seconds around the world. And we won't promote life-long learning opportunities for all (Goal 4) until girls have equal access to school and time to pursue the education that is rightfully theirs.

Truly responding to the needs of girls is the only way we can create the world we want for 2030. Here in Zimbabwe, for instance, "time poverty" is a significant and often-overlooked barrier to girls' education. Too many girls don't have time to play with other girls or to do the things that children should be doing because they have so many other responsibilities.

In some places, girls carry six times the workload as their brothers. That can make them late for school -- or keep them out of school altogether. Meeting the gender-equality mandate in Goal 5 means those responsibilities are more evenly allocated. And the consequences of not opening up more opportunities for girls can, in a very real sense, be a matter of life or death. Uneducated girls are three times more likely to marry early. That means they are more likely to have babies early (90 percent of all adolescent pregnancies are those of married girls), and because their young bodies are not ready to give birth, they are more likely to experience health complications -- or even to die. In fact, childbirth is a leading killer of adolescent girls in the developing world.

But gender equality and women and girls' empowerment can turn the tide by fostering an environment in which women and girls have access to the tools they need to climb higher: an education, for example, or income-generating skills or sexual-, reproductive- and maternal-health services that allow them to plan and space their pregnancies -- which means a healthier baby and a healthier mom.

For these reasons and many more, we should celebrate the standalone goal on gender equality as a huge step in the right direction. But we as a global community won't trek far toward achieving it without accompanying measures that hold governments accountable -- for the ways in which resources are spent, but also for the quality and accessibility of services those funds make possible.

The Sustainable Development Goals will frame a 15-year path toward greater opportunity -- particularly for women and girls -- and they will heavily influence how an estimated $2.5 trillion in global aid will be spent over that period. More must be done, however, to ensure that specific accountability measures are defined, instituted and funded -- and that the world's countries, like so many mothers in Zimbabwe, hold each other accountable.

To find out what you can do, visit here and here.

Article contributed by Ellen Chigwanda, Project Manager for Adolescent Girls Education, CARE Zimbabwe.