A few years ago, Spoorthi Shetty developed a rather unusual hobby. Every day, after returning from her university classes, she would spend the evenings outside her family home in Bangalore, India, looking for snakes.

“This used to be my regular routine for two years,” the now 21-year-old told Global Citizen.

Shetty, who had always been interested in the outdoors and wildlife, became obsessed with snakes after volunteering at a rainforest research station. When she spotted a snake for the first time, a colleague picked it up and placed it in her hands.

“The kind of sensation when the scales were on my skin… It felt — wow. It was amazing. At that moment, I fell in love. I decided I would work on snakes for the rest of my life,” she said.

Shetty read every book about snakes she could find and began reaching out to herpetologists (zoologists that specialize in reptiles and amphibians) across the country. She learned that 60,000 people in India die every year from snakebites, which are considered a neglected tropical disease (NTD), and that these cases accounted for half of all snake-related deaths in the world.

Wanting to make an impact in the snakebite capital of the world, Shetty joined Haavu Mattu Naavu, an initiative that aims to educate rural communities on snakebites. With Bangalore as her base, the young advocate travels throughout Karnataka state, to villages anywhere from 15 to 300 miles away, to reach those who are most prone to snakebites.

“What we tell them is snakebite is actually an accident and these accidents can be prevented by following personal safety hazards,” she said.

Spoorthi Shetty is pictured with a group after a session in Hiriyur, Karnataka. With Bangalore as her base, Shetty travels to villages throughout Karnataka state to reach those who are most prone to snakebites.

Spoorthi Shetty is pictured with a group after a session in Hiriyur, Karnataka. With Bangalore as her base, Shetty travels to villages throughout Karnataka state to reach those who are most prone to snakebites.

Spoorthi Shetty is pictured with a group after a session in Hiriyur, Karnataka. With Bangalore as her base, Shetty travels to villages throughout Karnataka state to reach those who are most prone to snakebites.

By taking preventative measures like using a light when outdoors at night, wearing footwear instead of walking barefoot, and using a mosquito net if they are sleeping on the ground, people can reduce their risk of being bit by snakes.

Shetty uses experiential learning to engage people when she talks about preventing snakebites and appropriate first aid.

In schools, she reads books about snakes to children, and walks around the property, pointing out places where snakes may be hiding, like in shady and cool areas. Shetty often makes recommendations like trimming bushes and tree branches so that they can’t touch windows or doors, which helps prevent snakes from entering classrooms.

In villages, Shetty hosts movie screenings in local languages. Up to 150 people gather on a typical night to watch the film and learn about snakebites.

According to the young advocate, popular films in India vilify snakes and contribute to misinformation. She said films commonly show scenes where actors are bit by snakes, apply pressure to the wound area, and suck the blood to remove the venom.

This approach is dangerous. When an individual cuts off blood circulation, it can cause more injury, leaving doctors with no choice but to amputate a limb.

Every year, close to 100,000 people in India lose a limb due to snakebites, Shetty said. In every village, she meets a few snakebite survivors who are amputees because they used incorrect first aid techniques.

“Imagine a farmer or daily wage farmer losing their limb — they can’t work for the rest of their life,” she said.

After being bit, many people visit healers for herbal medicine instead of getting treatment at a hospital, Shetty explained. The films she screens show people using the World Health Organization’s first aid protocols to treat snakebites.

To start, people need to move away from the snake. Shetty said after being bit, most people will attempt to kill the snake, and they will be bit several more times in the process. They should call an ambulance, remove tight objects from their body — like watches or bangles — as the area tends to swell, and call an ambulance to transport them to a hospital for anti-venom medicine.

Of the 270 species of snakes found in India, only four are highly venomous. Shetty makes sure people know this — and in every workshop, she makes people repeat the word “venom” several times.

This has earned her the name Aunty Venom Akka, meaning “elder sister, Venom.” When she passes by schools, she hears children call after her, “Aunty Venom, Aunty Venom.”

“I love snakes. I just love snakes,” Shetty said. “People don’t think the same way here. The moment they hear about a snake, they just want to kill it. And I tell them, we can co-exist.”

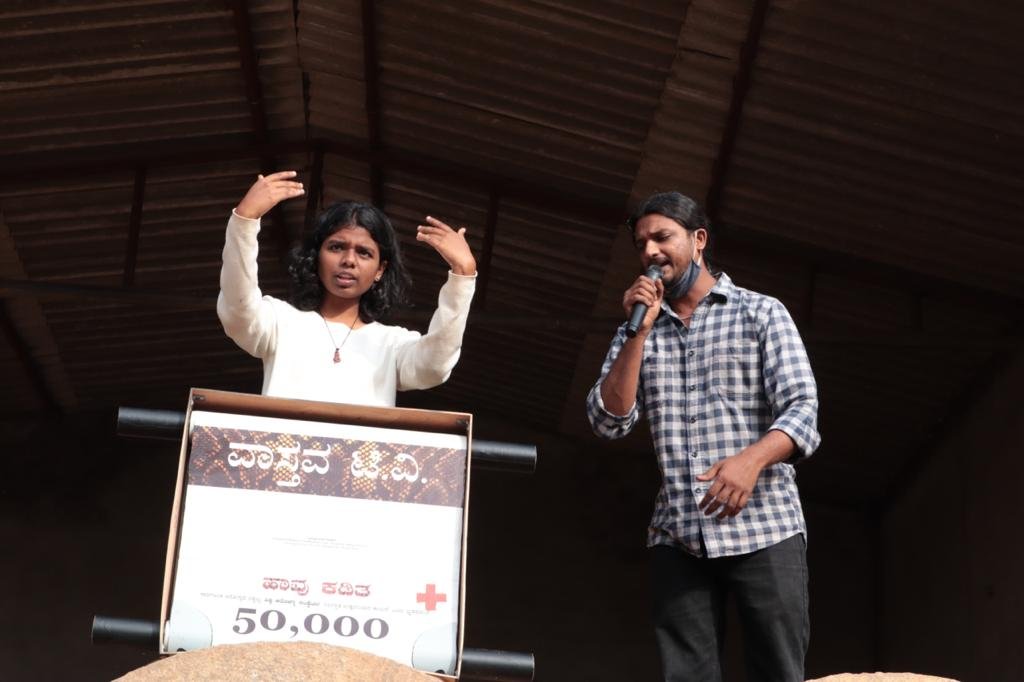

Shetty speaks to a crowd with Sanjeev Pednekar, founder of Haavu Mattu Naavu, in Challakere, Karnataka. Shetty had always been interested in the outdoors and wildlife, but became obsessed with snakes after volunteering at a rainforest research station.

Shetty speaks to a crowd with Sanjeev Pednekar, founder of Haavu Mattu Naavu, in Challakere, Karnataka. Shetty had always been interested in the outdoors and wildlife, but became obsessed with snakes after volunteering at a rainforest research station.

Shetty speaks to a crowd with Sanjeev Pednekar, founder of Haavu Mattu Naavu, in Challakere, Karnataka. Shetty had always been interested in the outdoors and wildlife, but became obsessed with snakes after volunteering at a rainforest research station.

Her message is working.

“I get calls [from people] saying, ‘I see a snake near my area. I don’t want to kill. Could you please rescue the snake and release it to another area?’” she said. “When I talk to them and approach them with positivity, they take it well, especially kids … It’s something that gives me immense happiness.”

The Last Milers is a profile series that highlights the people tackling neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which impact more than 1 billion people globally. By working to ensure equitable access to preventative measures, treatments, and information, these people support the elimination of NTDs in various ways, across different fields. These advocates aim to reach every last mile with necessary health care tools and services.

Disclosure: This series was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Each piece was produced with full editorial independence.