Earlier this year, striking images from the world’s first underwater protest against climate change began to appear on social media: an activist, wearing a mask and snorkel and floating at the heart of the Indian Ocean, holding up a sign reading “Youth Strike for Climate.”

The activist behind the protest, held in March on the Saya de Malha Bank, was Shaama Sandooyea, a 24-year-old marine biologist from Mauritius. She was taking part in a Greenpeace research expedition at the time, to study the area’s biodiversity.

The Saya de Malha Bank, off the coast of Seychelles, is home to the world’s largest seagrass meadow, stretching over 735 kilometres — which is a major absorber of climate dioxide, as well as a source of food and shelter for marine life, including endangered green sea turtles.

Shaama Sandooyea stages the first underwater demonstration to protest climate change in the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean. The Saya de Malha Bank is the largest seagrass meadow in the world and one of the biggest carbon sinks in the high seas.

Shaama Sandooyea stages the first underwater demonstration to protest climate change in the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean. The Saya de Malha Bank is the largest seagrass meadow in the world and one of the biggest carbon sinks in the high seas.

Shaama Sandooyea stages the first underwater demonstration to protest climate change in the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean. The Saya de Malha Bank is the largest seagrass meadow in the world and one of the biggest carbon sinks in the high seas.

But the world’s seagrass meadows are under threat — with the world reportedly losing around 7% of seagrass cover every year due to dredging, warming oceans, and more — and Sandooyea wanted to take action to help protect these vital environments.

Seagrasses are flowering plants that can be found in tropical, temperate, and even Arctic waters — and are actually the only flowering plants that can grow in marine environments.

They photosynthesize in the same way as other terrestrial plants, absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. According to environmental organization, Global Vision International (GVI), a single square metre of seagrass can release up to 10 liters of oxygen every day; while seagrass meadows globally hold around 15% of the carbon stored in the ocean.

We spoke with Sandooyea about what drove her to launch her protest, why seagrass is so important, and what she’d say to other young activists looking to raise their voices and take action for the environment.

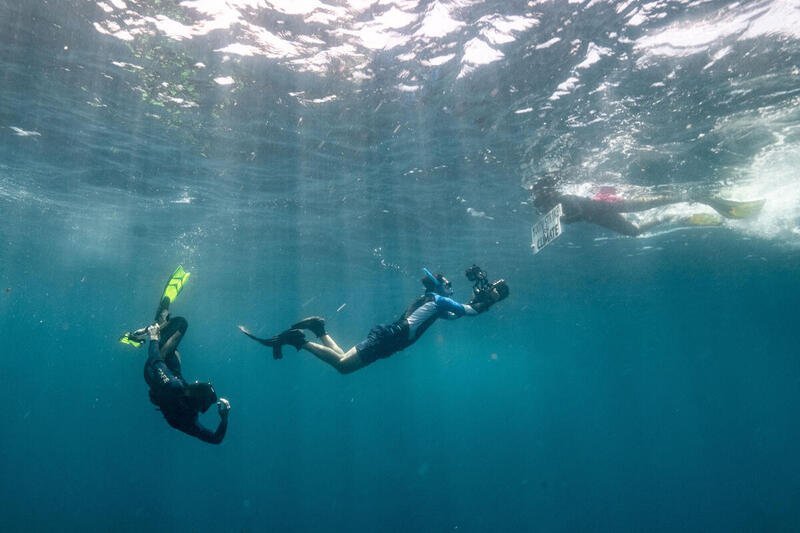

Videographer Maarten van Rouveroy films climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea holding a sign in support of the climate strike during a visit of the Arctic Sunrise to the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

Videographer Maarten van Rouveroy films climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea holding a sign in support of the climate strike during a visit of the Arctic Sunrise to the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

Videographer Maarten van Rouveroy films climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea holding a sign in support of the climate strike during a visit of the Arctic Sunrise to the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

Why did you become a climate change activist?

I became a climate activist because it’s unacceptable that people in positions of power are playing with the future of the planet.

How old were you when you started out, and what inspired you?

I started protesting about environmental issues when I was 20 years old, I think. I thought it was outrageous to see so many projects happening in Mauritius that were destroying habitats and ecosystems.

How did the idea of holding an underwater protest come about?

Being at the Saya de Malha for a scientific expedition to study the biodiversity in the world’s largest seagrass meadows, it was logical for me to hold an underwater protest.

Seagrasses are key ecosystems when we’re talking about fighting the climate crisis, and protecting the ocean and its ecosystems is the very first step towards concrete climate action.

Coming from Mauritius, which is an island that is suffering a lot from the climate crisis, we’ve been having a really long dry season and recently we’ve had flash floods around the island. To be able to demand climate action in the high seas was really wonderful, because it's like transmitting the message that we have from the island to everyone else on the planet.

We can't keep waiting any longer — we can't keep waiting until more people die and more lands and species are lost, and then that’s when we say, “Okay we need to act”. It has to be now.

Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea pulls on a mask and snorkel ahead of an underwater climate protest on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea pulls on a mask and snorkel ahead of an underwater climate protest on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea pulls on a mask and snorkel ahead of an underwater climate protest on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean.

What change do you want to see in the near future?

I want to see governments, world leaders, and corporations change. I want to see them be courageous enough to take action for the planet and for the people.

Why are you trying to protect seagrass in particular?

According to previous studies, seagrasses absorb carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests and store it longer in the seabed.

They also account for 10% of the ocean’s capacity to stock carbon and welcome a rich biodiversity.

Seagrasses have been underestimated for a long time now and it is time that we valorize it and recognize that the solutions are in nature itself — not in “new green technologies.”

What was it like to be underwater and seeing all the marine life?

In the beginning I couldn’t see anything and the water was kind of choppy, so it was a bit challenging. But then when I started diving it was different, it was clearer and I could see the fish swimming and if I looked really closely I could see the seafloor and the seagrasses. It was really green and pristine so the contrast between the blue around me and the green on the floor was just amazing.

I could also spot some corals growing in the seagrass, which I didn't expect and I was really amazed to see how life is growing. It was in the middle of the high seas of the Indian Ocean, and nowhere near the coast, so to see these forms of life growing was just wonderful.

As soon as I saw the seafloor, I literally thought this is why we need to protect this area because it's so full of life and it's not just the seagrass, the fish, the corals — it's also how these ecosystems are welcoming different forms of life, like sea turtles and dolphins. They make this area really rich and seabirds come to feed as well so it was just breathtaking to see that.  Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea, Greenpeace crew and crew search for shallow areas on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean ahead of performing an underwater climate protest.

Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea, Greenpeace crew and crew search for shallow areas on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean ahead of performing an underwater climate protest.

Climate advocate and scientist Shaama Sandooyea, Greenpeace crew and crew search for shallow areas on the Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean ahead of performing an underwater climate protest.

How long did the protest last?

I was underwater for an hour in total — I didn't have scuba diving equipment so I was just holding my breath and going down, then coming back up.

How did you feel during the protest?

At first when I started protesting it was a bit weird because no one has ever protested climate change underwater before. I was in the middle of nowhere and in a place which hasn't been really chartered, but as I started protesting it all made sense.

It was really logical to me why I would have to protest here because as an activist for more than two years now, we've been asking for and we've been demanding for climate actions.

What would you say to other young people who want to become climate change activists but don’t know how or where to begin?

I would say reach out and get in touch with other climate activists locally, or in other countries too, so they can guide you.

Reach out to me if you want. Each country is different and it’s important to adapt.

Shaama Sandooyea prepares her sign for the climate strike onboard the Arctic Sunrise in the Indian Ocean. A team aboard the ship are on an expedition to the bank to contribute to a better understanding of the wildlife and diversity of the region.

Shaama Sandooyea prepares her sign for the climate strike onboard the Arctic Sunrise in the Indian Ocean. A team aboard the ship are on an expedition to the bank to contribute to a better understanding of the wildlife and diversity of the region.

Shaama Sandooyea prepares her sign for the climate strike onboard the Arctic Sunrise in the Indian Ocean. A team aboard the ship are on an expedition to the bank to contribute to a better understanding of the wildlife and diversity of the region.