The eradication of wild poliovirus is within sight — but only if the world remains committed and financially invested, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) announced on Tuesday at a virtual event amid World Immunization Week.

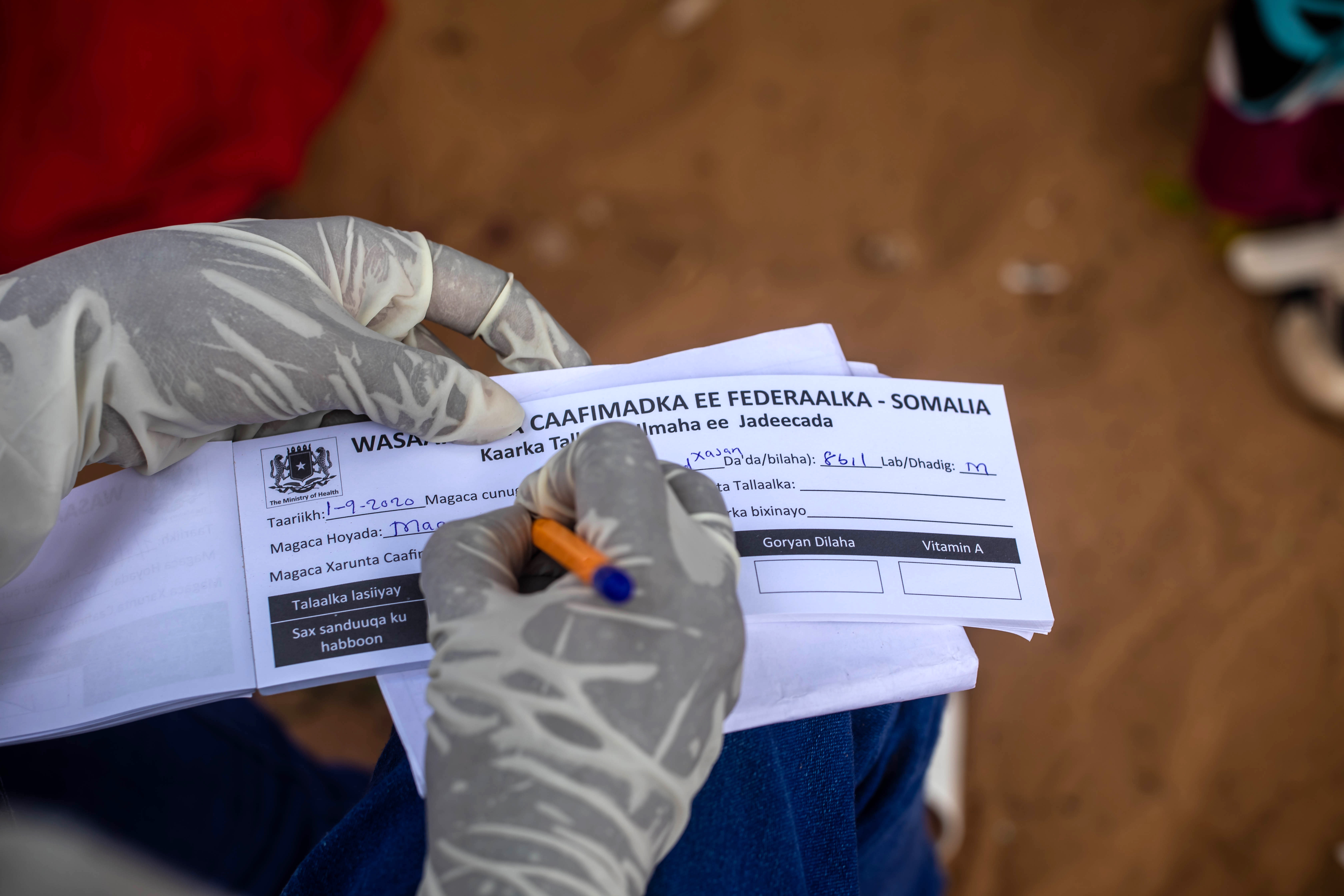

The event, Investing in the Promise of a Polio-Free World, marked the launch of GPEI’s investment case for its 2022-2026 polio eradication strategy. It brought together global partners, leaders of polio-affected countries, donors, and health workers to highlight the tactics that will be used to eradicate polio around the world. If fully funded, the organization's strategy would result in the vaccination of 370 million children per year for the next five years.

Polio is a highly infectious viral disease transmitted by person-to-person spread, mainly through the fecal-oral route or, less frequently, from droplets from a sneeze or cough of an infected person, or by a common vehicle (e.g. contaminated water or food). The virus, which can invade a person’s nervous system and cause paralysis, or in some cases death, mostly affects children under 5 years of age. The polio vaccine, administered in either two or four doses (depending on the vaccine), can protect a child for life.

While wild polio cases have decreased by 99%, the global health community continues to face great challenges in its fight to eradicate this disease — particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cascading effects it has had on access to health services, such as routine immunizations, worldwide.

As a senior epidemiologist working in the polio department at the World Health Organization headquarters in Geneva, Dr. Zubair Mufti Wadood supports with planning and implementing polio eradication programs. Global Citizen caught up with Wadood to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted polio vaccination campaigns and what this means for children around the world.

Yemen was declared polio-free in 2006, but announced an outbreak in 2020. The country is now dealing with outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 and type 2, which thrive in areas with low vaccination. Polio workers aim to reach every child.

Yemen was declared polio-free in 2006, but announced an outbreak in 2020. The country is now dealing with outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 1 and type 2, which thrive in areas with low vaccination. Polio workers aim to reach every child.

Having worked in polio prevention for nearly two decades, can you share with us the experiences of the polio survivors that you’ve met? What does life look like for people who live with this disease?

I always say that polio does not affect children or individuals — it affects families and communities. The life of the polio-affected child is extremely challenging. Even with a mild case, the child is almost never independent. Typical milestones like crawling, standing, and walking are affected and significantly delayed.

These children need specialized rehabilitation, professionals, and institutions to help them and that has costs [and often isn’t accessible]. Most of the children affected by polio belong to families from low socioeconomic classes, and their life already has challenges. Usually as the child grows, these challenges deepen because a lack of rehabilitation starts to affect other parts of the body, including the spine, leading to [other] conditions.

I will never forget one father I met, whose child had polio. He said, ‘I always pray to God not to punish my child for any bad deeds that I have done.’ That tells you the state of mind of these families.

Over the last two years, we’ve seen the COVID-19 pandemic and its lockdowns impact every aspect of life. What impact did this have on polio campaigns globally?

This pandemic was unprecedented in our lifetime. We were hearing about more and more infections spreading around the world and people [were terrified]. On March 24, 2020, the polio oversight board issued urgent recommendations, including temporarily stopping polio vaccination campaigns.

Dr. Samreen Khalil, a WHO polio eradication officer, conducts environmental sampling for polio in Shaheen Town, Pakistan. With the help of WHO, the country was able to draw on its experience in the fight against polio in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Samreen Khalil, a WHO polio eradication officer, conducts environmental sampling for polio in Shaheen Town, Pakistan. With the help of WHO, the country was able to draw on its experience in the fight against polio in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Close to 30 countries had to postpone or cancel 62 campaigns, which is a huge number. Another 14 countries halted their vaccination campaigns of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV).

Resultantly, what happened was a significant geographical spread of poliovirus — both within countries that were already affected and international spread.

When did these campaigns resume?

Generally, polio campaigns were completely suspended between March and June [2020], so countries who were experiencing outbreaks went almost four months without a polio campaign.

In an outbreak setting for a disease like polio, four months is very significant. Even four weeks is significant, because every week of a delayed response to a poliovirus outbreak allows more children to be paralyzed, and allows more geographical spread within the country and beyond international borders.

In Pakistan and Afghanistan, the campaigns were temporarily suspended between March and August [2020]. They resumed in September, so that six-month gap is very significant in these countries, which are endemic for polio.

A polio worker from Mazar-e-Sharif in Balkh province, Afghanistan, provides health information during a house visit.

A polio worker from Mazar-e-Sharif in Balkh province, Afghanistan, provides health information during a house visit.

When polio campaigns resumed, did their approach change given that we’re still in a pandemic?

Implementing polio campaigns in this environment of COVID-19 was entirely different. There were well-tailored community mobilization efforts focusing on COVID-19 dynamics. [Health workers] had to incorporate infection prevention and control, and social distancing, so that communities receive the vaccination teams in a cordial way and without any perception of risk.

What does the data show us about what happened during these months of halted campaigns during the pandemic?

The second half of 2020 was definitely a period of intensified polio transmission in Pakistanand Afghanistan, as well as in outbreak-affected countries, mostly the African region.

In terms of numbers, Afghanistan had 29 wild poliovirus type one cases in 2019. In 2020, the country reported 56 cases — almost close to double. In Pakistan, although the case numbers slightly decreased … we see that all the efforts made towards [eradicating polio] were reversed or significantly affected by the pandemic.

The polio surveillance function was not as efficient as it was before [the pandemic]. One of the reasons was that a number of health facilities were not functioning. Also, people were scared from a community perspective to go to health facilities and seek health care, because of a fear of COVID. So, there was a significant decrease in the number of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases. These are the cases which can potentially be polio and are tested.

From January to July 2020, compared to the same period in 2019, there was a decline of 34% of the reporting of AFP cases, indicating that the polio surveillance was significantly affected during the pandemic.

These numbers — like 56 polio cases in Afghanistan — may seem low to some people. When it comes to polio, what reality do these numbers reflect?

We have to look at this from the population immunity lens. For every case of a child getting paralytic polio, there are 200 to 1,000 kids who are infected. The rest may be affected in a way that manifests as a mild flu-like illness and over 90% of infections are asymptomatic.

If polio campaigns are implemented in a inconsistent way and population immunity is not built up to the level where we are able to stop transmission, there is always a risk of an international spread. If the virus reaches a place where there are many unvaccinated children, it can [be a disaster].

In Al-Buraika district, a poor neighborhood in Aden, Yemen, Muneera Abdo is a polio vaccinator who travels door to door, vaccinating children under 5 and raising awareness about the importance of vaccination among parents. Photo taken in June 2021.

In Al-Buraika district, a poor neighborhood in Aden, Yemen, Muneera Abdo is a polio vaccinator who travels door to door, vaccinating children under 5 and raising awareness about the importance of vaccination among parents. Photo taken in June 2021.

The end of polio is in sight, but the virus is trying its best to stage a revival. The Comeback We Never Wanted is a content series that looks at how and why polio outbreaks have increased in recent years, diving into issues connected to access to health care, touching on the impact of COVID-19, the difficulty of navigating conflict zones and terrorist groups, and more.

Disclosure: This series was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.