For months, US lawmakers have been embroiled in a furious debate over the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Act (DACA) — the legislation which protects people brought illegally into the US as children from deportation — and President Donald Trump’s infamous wall.

As Congress resumed its heated conversation around immigration this week after a brief government shutdown, I was confronted with a powerful visualization of the history of today’s immigration debate at “The Immigrants,” a photography exhibition on display at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York (on display until Jan. 27).

“Are you a native New Yorker?” the exhibition’s curator, Pak So, asked me.

We were standing in a room lined with photos of children at school and on playgrounds in New York City’s Lower East Side neighborhood, historically, one of its most ethnically diverse. So, who came to the US from Hong Kong at age 8, confessed that he had a soft spot for these photos, having grown up near Chinatown and the Lower East Side himself.

I told him no. I was born and raised in Singapore, which, coincidentally, is a less than three-hour flight from his country of birth.

As So and I, two people of Asian origin, walked through a visual history of US and global migration — from World War II refugees bound for Ellis Island to Japanese-Americans relocating to internment camps to Syrian refugees arriving on Lesbos, Greece — I shared that my father, the grandson of European Jewish immigrants, is from upstate New York.

He’s from Rochester, New York, actually, which, as it turns out, is where So attended school for several years.

Millions of people in the US have stories like So’s and mine — America is a nation of immigrants.

And exchanges like the one So and I shared are the reason he felt “The Immigrants,” which features photographs by more than 40 artists, was an important show to put up at this moment.

Take Action: Refugee? Migrant? Human Being. Show Your Support for All People

So said he was first inspired to create the exhibition when he stumbled upon one of the earliest protests against Trump’s travel ban last year in Washington Square Park and so it’s fitting that the show starts with images of Ellis Island and New York City, one of the US’s main immigration points for over 60 years.

Trump’s travel ban, the one So witnessed being protested, is now being considered in its third iteration and has been widely criticized as racist and anti-Muslim, but people of every race and religion have immigrated to the US for centuries.

“The Immigrants” showcases the diversity of people who came to the US in hopes of finding safety and living the “American Dream.” People from around the world came to the US, passing through New York’s Ellis Island and California’s Angel Island — dubbed “the Ellis Island of the West.” And though most of the images featured in the exhibition are from the first half of the 20th century, they are poignantly relevant to today’s immigration discussion.

The show’s photographs highlight the treatment of immigrants once they have arrived in the US, including images of Chinese immigrants at work on the Transcontinental Railroad, Japanese-Americans forced to relocate during World War II.

Japanese-American Tatsuro Matsuda commissioned the "I am an American" sign for his family's store in Oakland, California and hung it in the window the day after Pearl Harbor.

Japanese-American Tatsuro Matsuda commissioned the "I am an American" sign for his family's store in Oakland, California and hung it in the window the day after Pearl Harbor.

Japanese-American Tatsuro Matsuda commissioned the "I am an American" sign for his family's store in Oakland, California and hung it in the window the day after Pearl Harbor.

“The Immigrants” showcases the work of Dorothea Lange, whose photos of Japanese-Americans the government deemed “too sympathetic” after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

But migration is a global phenomenon, and “The Immigrants” makes that clear. Though much of the exhibition focuses on migration to the US, one display is dedicated to refugees and the events that caused them to flee their home countries. A portion of the proceeds from the show will benefit the International Rescue Committee’s effort to support refugee families.

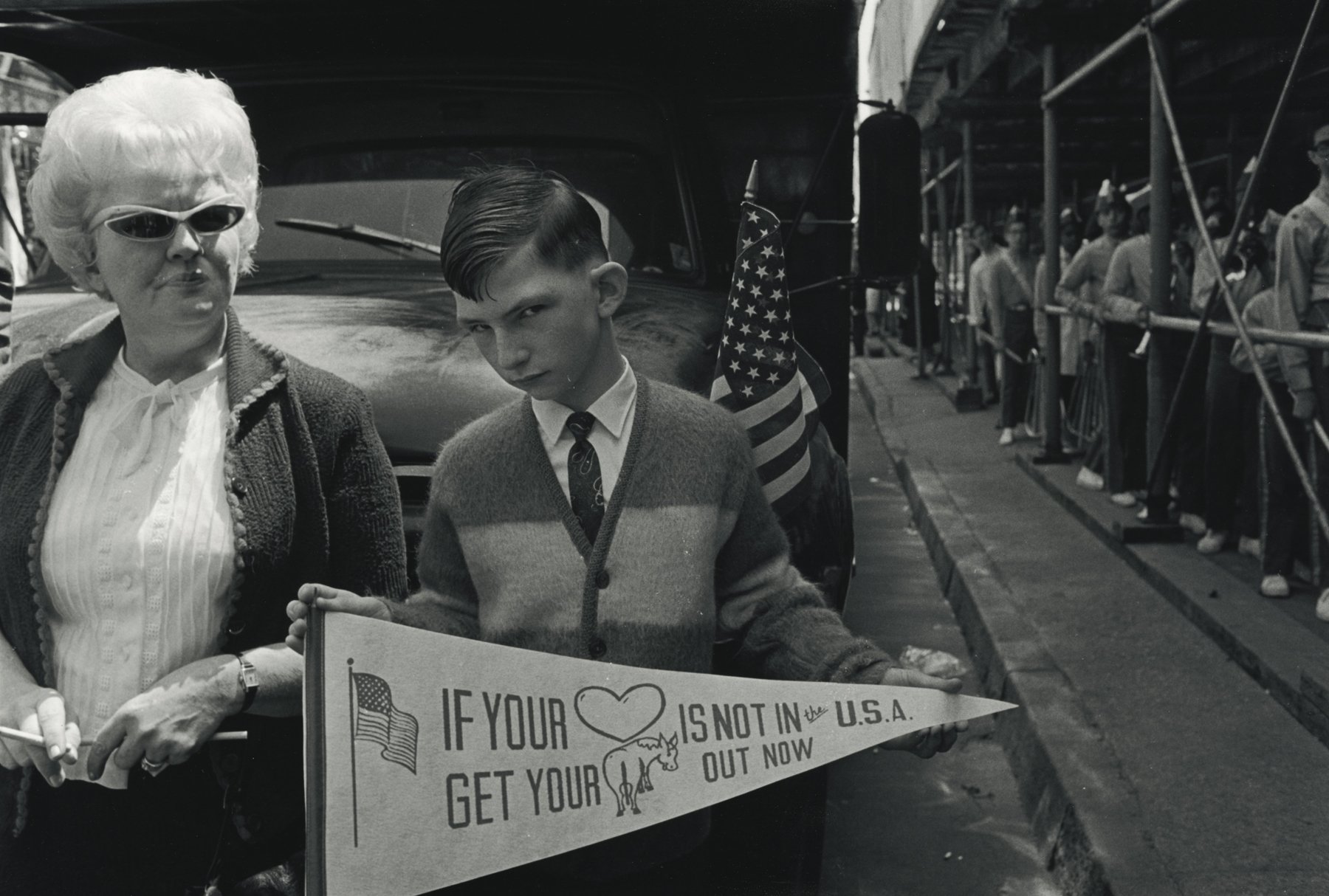

The exhibition moves seamlessly back and forth in time, showing that anti-immigration sentiment and xenophobia are as alive today as they were 50 years ago.

Pro-Vietnam War Parade, New York City, 1968

Pro-Vietnam War Parade, New York City, 1968

Pro-Vietnam War Parade, New York City, 1968

San Ysidro, California, 1979

San Ysidro, California, 1979

San Ysidro, California, 1979

An unlikely image from the past — a photo of musician John Lennon, his hand in a peace sign, in front of the Statue of Liberty — pulls the show’s very current message about the people who made America great sharply into the present.

Read more: A Federal Judge Just Temporarily Blocked Trump’s DACA Decision

In the early 1970s, Lennon was charged with overstaying his visa and faced deportation, though FBI files revealed that Lennon was targeted for deportation by the Nixon administration, which opposed his anti-war activism, according to NPR. Desperate to keep his client in the country, Lennon’s lawyer, Leon Wildes, found a little-known policy that enable immigration authorities to hold off on deportations for political or humanitarian reasons.

John Lennon, New York, 1974

John Lennon, New York, 1974

John Lennon, New York, 1974

Wildes succeeded in getting Lennon a green card, but more importantly put the spotlight on the “secret policy,” which decades later became the grounds for the creation of the DACA program.

Read more: The Faces Behind the Figures: 5 Dreamers Share Their Hopes and Fears

The show ends at what is arguably the beginning of US immigration history, with a photo of members of a Native American tribe riding away on horseback called “The Vanishing Race.”

So pointed out that anyone who to came to the US after the Native Americans could be considered immigrants, and that, today, those who believe themselves to be a “vanishing race” are the ones calling for more walls and closed borders.

In an increasingly globalized world, migration is not a phenomenon set to disappear any time soon. “The Immigrants” provides a powerful glimpse into the history of humans moving about the world and offers a much-needed reminder of who made America great.

The Vanishing Race, 1904

The Vanishing Race, 1904

The Vanishing Race, 1904