On Christmas Day in 1990, 17-year-old Lawrence Bartley went to a showing of The Godfather III at a Long Island, New York, theater — and it changed the course of his life.

During the film, Bartley and his friends got into a heated argument with another group of teens in the audience. As the situation escalated, the two groups began shooting.

Bartley fired once in the dark theater, unable to see where his shot had landed, but at the end of the night, 15-year-old Tremain Hall was dead. The teen had been sitting in the audience with a friend. He wasn’t there with either of the groups.

Police recovered 25 bullets, and though they initially had trouble determining whose gun had killed Hall, the prosecutor charged Bartley with the single fatal shot.

He was convicted and sentenced to 27 years to life.

That was nearly three decades ago. Bartley was released on parole 11 months ago after serving 27 years and two months in prison.

In the time that he was incarcerated, Bartley earned an undergraduate degree in behavioral science and a master’s in professional studies. He became an advocate against gun violence and a leader and role model among those incarcerated with him.

But staying positive and motivated wasn’t always easy.

At times, the possibility of parole seemed like a distant promise that would never be fulfilled. And if it ever was, it seemed likely that freedom would be fleeting.

“The only news you’d see reported is about parolees getting out and then committing another crime, because they couldn’t get a job and eat,” Bartley told Global Citizen.

But now that he’s out — and he plans to stay out — Bartley wants to give people “on the inside” hope.

When Bartley entered prison, cellphones — not yet widely used — were too large for some purses, let alone pockets. Tape players were more common than CD players. And computers were a luxury, not a typical household item.

He had a lot to catch up on, but he set his mind to doing so as quickly as possible. He picked up technology and the subway system quickly and adjusted to life at home with his family. What’s taken a little more time is processing that he’s no longer inside.

“I went into that facility and didn’t come out for another 27 years. Each day inside, I dreamed of getting out. I used to always walk around my cell and say, ‘Damn, I’ve gotta get out of here,’” Bartley said.

”Even now sometimes I find myself saying, ‘you gotta get out’ and then I'm like … I'm out … I'm here already,” he said, sitting in his office in midtown Manhattan.

But he hasn’t forgotten about people who are still inside.

After being incarcerated for 27 years and two months, Lawrence Bartley had to re-adjust to life on the outside. That included learning the Subway system and adopting new technology.

After being incarcerated for 27 years and two months, Lawrence Bartley had to re-adjust to life on the outside. That included learning the Subway system and adopting new technology.

After being incarcerated for 27 years and two months, Lawrence Bartley had to re-adjust to life on the outside. That included learning the Subway system and adopting new technology.

Bartley now works at the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization focused on criminal justice issues, where he’s producing a new print publication for distribution in jails and prisons called News Inside.

The Marshall Project first took notice of him last year while he was still incarcerated, publishing an essay he’d written about the long and frequently discouraging process of trying to win parole, at the urging of a friend.

When the friend had first suggested that he write the essay, Bartley declined.

“I was like … I can’t do that right now! I’m fighting for my life, literally,” he remembered.

“But I thought about it and thought about it, and finally I said if I write this story, it won't just be for me — it would be for everyone behind me that can't really articulate their thoughts.”

Hope isn’t the only thing Bartley wants incarcerated people to get out of News Inside.

It’s that same desire to support others that led Bartley to create News Inside. The publication features a selection of the Marshall Project’s articles, curated by Bartley to highlight stories of potential and progress within the criminal justice system.

The first issue, published in February, features stories about a theater program for incarcerated people, an initiative called Turning Leaf that “trains the brain” to help reduce recidivism, an article about the bonds and friendships formed while incarcerated, and Bartley’s essay.

He and the Marshall Project had initially set out to get News Inside into 20 facilities in 10 states within the year, but within 60 days of printing, it was being circulated in 225 facilities across 30 states for free. The publication has even been requested by a facility in Canada.

Hope isn’t the only thing Bartley wants incarcerated people to get out of News Inside. He also wants to increase access to information within jails and prisons. The lack of relevant and current information in facilities is a problem Bartley grappled with while working toward his degrees at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York.

Professors would task him with writing research papers and would require a minimum of eight sources, Bartley said.

“But we didn't have internet, we had a system called Encarta,” he recalled.

Encarta, a digital encyclopedia produced by Microsoft, has been effectively defunct since 2009. Even in 2014, Bartley said prisoners only had access to the 2008 version of the program.

They had textbooks, but they, too, were often outdated or limited in scope. And even newspapers brought in by corrections officers were off-limits, unless they had been thrown out. Newspaper subscriptions could be purchased individually, but Bartley said he wasn’t able to afford them on his prison salary.

His experience isn’t uncommon among incarcerated people. In some facilities, people aren’t even allowed to send incarcerated individuals hardcover books — only paperbacks.

“In general, at present, there are just very little resources for incarcerated people to educate themselves,” Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, told Global Citizen.

“Even if incarcerated people have access to the internet in a prison, it’s going to be severely restricted,” she said. “Even if they have iPads or handheld tablets, they tend to be very limited in terms of apps and programs.”

“I don't want them to be released with angst. I want them to be released with a sense of hope.”

But studies show that offering education programs in prisons helps to aid re-entry into communities and reduce recidivism — the likelihood of engaging in criminal activity again. Investment in education for incarcerated people has waned over the past few decades, after the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, a federal bill passed under President Bill Clinton, rendered prisoners ineligible for Pell Grants.

These grants have been the main source of support of education for low-income students across the country, since the 1970s. And experts and advocates have been calling on lawmakers to reinstate incarcerated individuals’ access to these grants more recently. Doing so, they argue, would also help to stop cyclical poverty and crime.

In the meantime, nonprofits have stepped up to try to address the education funding void and lack of programs for incarcerated people, Eisen said. The programs that Bartley completed at Sing Sing are supported by nonprofits and rely on volunteers.

Once in the college program — which, according to Bartley, once had a waitlist of nearly 600 people out of an inmate population of about 1,700 — he was determined to get his degree and excel in the program.

So Bartley and his classmates resorted to asking professors to bring in articles downloaded from the internet — which until last year he had never even seen. But even this required a lengthy approval process, and wasn’t always fruitful. Bartley said he and his classmates didn’t even know what kind of information to ask for until they saw it.

“I had a crush on her when I was young … and she had no crush on me.”

He pushed through anyway. But Bartley said he might have been even more enthusiastic about studying if he’d been able to read and write about topics directly related to his life.

“Instead of taking a week to do a paper, I would probably take just three or four days because I’d put my all into it.”

That’s what he wants News Inside to inspire incarcerated people to do. He added that the publication is not only meant for those in college or educational programs while incarcerated, but also, he hopes, the general prison population, and people in solitary confinement.

Bartley said he knows how being inside can make people feel “trapped with nothing but their thoughts” and that can turn into angst.

“If those thoughts can be fed appropriately, I think that would help take away all the angst that they feel,” he said. “I don't want them to be released with angst. I want them to be released with a sense of hope.”

After being released on parole 11 months ago, Lawrence Bartley now works at the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering criminal justice issues. Bartley created News Inside, a publication for people incarcerated in jails and prisons.

After being released on parole 11 months ago, Lawrence Bartley now works at the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering criminal justice issues. Bartley created News Inside, a publication for people incarcerated in jails and prisons.

After being released on parole 11 months ago, Lawrence Bartley now works at the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering criminal justice issues. Bartley created News Inside, a publication for people incarcerated in jails and prisons.

“I know what it's like to almost become bitter,” Bartley said.

For the first 13 years of his incarceration, Bartley was mostly placed in various facilities further upstate — the closest one was about four hours from New York City. He would get at least one visit a year, but not many, he said.

“I remember being in, and being by myself one day when people were getting visits. It was a Saturday morning, and I wanted one so bad. My stomach started jumping and all these physical things would happen to me because I wasn't able to see anyone,” he said.

“Contact with other people, especially seeing children, is very important when you’re incarcerated,” he explained.

In fact, the first visit he ever got while at a facility upstate was from his childhood love, Ronnine.

“I had a crush on her when I was young … and she had no crush on me,” Bartley said, with a cheeky smile.

At 15, they dated for “what seemed like forever, but was maybe eight months,” then broke up. And just a couple of years later, Bartley was sentenced to 27 years in prison, and possibly life.

“I felt like I’d run a marathon for years but the finish line kept being pulled back on me.”

They remained in touch, but it wasn’t until many years later than she came into his life permanently. He and Ronnine are now married, with two sons, 11 and 6.

“When you have that kind of support and people care about you, you don't have to worry about whether you're good enough or have low self-esteem,” Bartley said. “You can just be yourself … That allowed me to do other things in the facility with a little bit more confidence [too].”

Approximately 2.3 million people are incarcerated in the United States, and most of them are parents. Allowing those parents to stay connected to their families has positive impacts on both children and their parents. And studies have shown that it increases the likelihood of formerly incarcerated people successfully re-entering their community and avoid recidivism.

But maintaining those bonds can be difficult, particularly for low-income families, whose loved ones are incarcerated in faraway facilities. Bartley’s family spent thousands of dollars on phone calls throughout his incarceration.

At Sing Sing, just an hour’s drive from Manhattan, they were able to spend two days in a “modular home” that simulates a family environment at the correctional facility every 90 days as part of its Family Reunion Program.

His family is what kept him going through an arduous parole appeal process after his first request for parole was denied.

“I felt like I’d run a marathon for years but the finish line kept being pulled back on me,” he said.

“I knew the odds were against me. But I was able to have a family that loved me and supported me and I knew that my family's hopes and their happiness was riding on whatever presented before [the parole board],” he said.

So he kept at it. Normally, an inmate would have to wait another two years to be reconsidered, but Bartley, while devastated, was not deterred. Due to a combination of appeals, deadlocked decisions, and postponements, he appeared before the board five times in seven months, before finally being granted parole.

In 25 months, he can be released from his parole sentence, if he “stays out of trouble,” he said.

Bartley grew up mostly in Queens and now lives there with his family, but the Queens his sons call home is a far cry from the place in which he spent his teenage years.

Born in the Bronx, Bartley moved to Jamaica, Queens, at 14 after his parents got divorced. He moved from what he described as a “nice suburban community” to one that was more “urban,” where drugs, crime, and violence were common.

“That’s where my troubles began,” he said. He began hanging out with people in the neighborhood and wanted to fit in with what was “cool.”

“I ended up getting myself shot five times,” he said. By that point, Bartley was 16, and while he survived, he was traumatized. He never wanted to be caught defenseless again, so he got a gun.

“I'm not a notorious serial killer like you’re making me out to be.”

A good student with dreams of going to college, Bartley saw education as his way out. He started taking night classes and going to summer school on top of his usual classes in order to graduate a semester early.

“I knew I was living wrong and I just wanted to get out of the neighborhood. I wanted to go to college somewhere far away and I wanted to get rid of that doggone gun,” he remembered.

“I knew if I was in the neighborhood I was going to need that gun, but if I could get out sooner, I could give it up.”

Bartley would have graduated ahead of schedule, in January 1991, but he was arrested in December.

Lawrence Bartley's bail was set at $1 million, which his family could not afford. He spent 17 months in Rikers Island and Nassau County Detention Center before being convicted and sentenced. His daughter was born a week into his incarceration.

Lawrence Bartley's bail was set at $1 million, which his family could not afford. He spent 17 months in Rikers Island and Nassau County Detention Center before being convicted and sentenced. His daughter was born a week into his incarceration.

Lawrence Bartley's bail was set at $1 million, which his family could not afford. He spent 17 months in Rikers Island and Nassau County Detention Center before being convicted and sentenced. His daughter was born a week into his incarceration.

His bail was set at $1 million. Bartley was incredulous. He recalled the assistant district attorney sent him a look that said “I’m going to fry you” as he requested the bail amount.

Inside, Bartley was screaming. He wanted to cry, but feared being beaten if he did.

“Wait a minute! I’m in high school. I love my grandmother. I love my family,” he remembered thinking.

“I'm not a notorious serial killer like you’re making me out to be.”

Instead, what came out were angry teenage grunts that Bartley said probably seemed like defiance.

“When I think of that bail amount, I think of all those things.”

Bartley said he had been in trouble and gotten arrested once before. His bail then had been set at $750, which his family was able to pay. But this time, because his family couldn’t afford to make his bail, the teenager spent 17 months trying to fight his case — splitting his time between the Nassau County Detention Center and Rikers Island. He missed the birth of his daughter, who arrived a week after he was arrested.

Bartley said he “definitely” would have been better able to fight his case if he’d been out on bail.

“People who are detained pre-trial — compared to their counterparts who are similarly situated in all of the same circumstances but are out of jail literally — end up with more serious convictions with longer sentences and basically worse legal outcomes,” Insha Rahman, program director at the Vera Institute of Justice, said.

“Research shows that being detained pre-trial has really serious consequences for both your legal case and outcomes as well as for you as a human being,” she added.

Of the hundreds of thousands of people in jail in the US, most have not yet been convicted of a crime, according to data gathered by the Prison Policy Institute. And many are there because they cannot afford to pay their bail. This means that they are away from their families and communities for days, weeks, months, and even years, before being convicted of a crime. And this can make people vulnerable to psychological and physical harm.

The cash bail system was created to ensure that people charged with crimes appeared for their court dates, but experts and advocates say, in practice, it now simply criminalizes poverty and disproportionately impacts communities of color.

“We're a country that is really on a binge of throwing the book at people and believing that long sentences are the only way to get retribution and get justice. And we have an over reliance on incarceration in general … like if you don’t show up to court, we’re going to put you in jail,” Rahman said.

Data shows that in cities where the use of cash bail has been reduced or eliminated, the overwhelming majority of people do show up to their court appointments. Experts say that, ultimately, what the system does is penalize those who can least afford it.

“It pushes people to develop these harsh feelings that the world is against them, and in so many ways, they’re right.”

“There's actually a very obvious way to address that inequity,” Rahman said.

“For every dollar that we invest in the criminal justice system in programs in jails and prisons, we should be investing at least that much money, if not more, in the schools, housing, and community resources of the neighborhoods that people in the criminal justice system come from.”

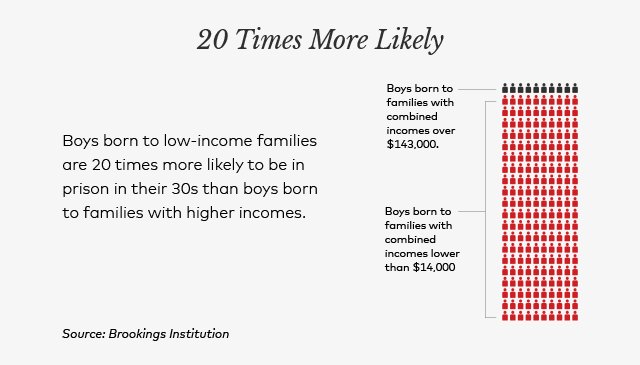

Seeing the cycle of poverty that the system perpetuates can be debilitating. Bartley said poverty was “absolutely the norm” among those incarcerated.

“Many people who are incarcerated are also poor — and this is not to take anything away from the victims of those crimes that shouldn’t have been committed — but people feel like the system is setting them up for failure in so many different layers of ways and all they see is negativity,” he said.

“It pushes people to develop these harsh feelings that the world is against them, and in so many ways, they’re right.”

At 17, Lawrence Bartley was given a sentence of 27 years to life. While incarcerated he earned two degrees, though the prison often lacked the resources he needed to complete his coursework.

At 17, Lawrence Bartley was given a sentence of 27 years to life. While incarcerated he earned two degrees, though the prison often lacked the resources he needed to complete his coursework.

At 17, Lawrence Bartley was given a sentence of 27 years to life. While incarcerated he earned two degrees, though the prison often lacked the resources he needed to complete his coursework.

But through News Inside, Bartley wants to inspire hope. Through the path he forged for himself, he is leading by example and believes that success on the outside is possible for everyone on the inside.

“So mostly, my message to people on the inside is that I want them to take value in themselves. I want them to think, if I come out and don't have any family, no place to stay, I can still make it,” he said.

“And I am not just going to make it, to tread water, I'm going to be great because I have value and I'm going to work on my craft while I'm inside.”

This week Global Citizen is publishing a series of stories focused on the impact of cash bail and the criminal justice system on people affected by poverty. Go to End Bail, Fight Poverty to read these stories.