Public sexual harassment is an issue in every society. But misogyny and sexual harassment in public has been so normalised that often bringing up the issue of behaviour such as cat-calling or wolf-whistling can lead it to be dismissed as “just a joke.”

Around 90% of women in the UK have experienced public sexual harassment, with victims as young as 11, according to a UN Women UK YouGov survey. Despite its impact, however, there is currently not much protection against it — in the UK, you can be fined for littering but not for sexually harassing a child in public.

Luckily, there are people fighting to change the law and shift attitudes towards these ingrained behaviours in Britain, and 23-year-old Chiamaka Elumogo — lead campaigner for Our Streets Now — is one of them. The grassroots campaign group was set up by two sisters fed up with street harassment, Maya Tutton, 21, and Gemma Tutton, 16, in 2019. It calls for new laws that would criminalise public sexual harassment as well as providing educational campaigns.

On Dec. 3, as a result of advocacy from groups including Our Streets Now, it was announced that a new review of hate crime legislation in Britain is expected to ask the government to consider criminalising public sexual harassment — which would include lewd comments, pressing against someone in a sexual way on public transport, cornering someone, catcalling, and persistent sexual propositioning.

The Law Commission, a regulatory body that recommends new laws, is recommending a draft bill that would introduce fines for this type of harassment. However, as part of the same review the Law Commission rejected the proposal to make misogyny a hate crime.

Alongside her studies — she is a final year medical student at the University of Buckingham — Elumogo helps the campaign by running Our Streets Now’s Twitter account and using her voice to raise a profile for the group. She has been passionate about intersectional feminism since she first started learning about it when she was 15 and says she leapt at the chance to get involved with Our Streets Now.

"Being able to articulate what public sexual harassment is, the nuances around it, and the problems it causes, is something I am grateful for Our Streets Now for, because it is such a normal part of our lives," she says. "When I was younger it used to happen all the time and there was no language to explain or understand it. Whereas now, having joined the organisation, I feel quite grateful for that knowledge.”

As campaigners globally mark the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign, which runs from Nov. 25 to Dec. 10, Elumogo sat down with Global Citizen to tell us more about what Our Streets Now is calling for and why.

What does Our Streets Now do?

Our Streets Now started with two sisters, Maya and Gemma Tutton, who started a petition to make public sexual harassment illegal in the UK in 2019. Since I joined in April 2020 it has grown into huge multi-faceted organisation with the main goal to end public sexual harassment in the UK.

First, there is the legal campaign being run in collaboration with Plan UK, a children’s rights and gender equality charity, and two lawyers who work on human rights law and violence against women cases, Dexter Dias QC, and Dr. Charlotte Proudman. They have drafted a proposed Bill to make public sexual harassment a criminal offence in the UK.

Additionally, there is a higher education campaign which is working to end public sexual harassment on university campuses and other higher education institutions. The goal is to try to get more robust rules against public sexual harassment and support for victims. Around 84% of students have experienced sexual harassment on their campus or around university, according to a study conducted by Our Streets Now.

We also have Our Schools Now, which targets primary and secondary schools. They've got some fantastic resources for curriculums and teaching about prevention — such as the right language to use, and how we can all challenge such behaviour. It's unfortunate that we have to do it, but I think the best route to improving safety for women, girls, and all marginalised genders is to start at the root of the problem and start teaching people from a young age that the behaviour is not acceptable. It’s also important to provide the tools to support ourselves and each other when we do see it happen.

How would you define public sexual harassment?

Public sexual harassment encompasses any kind of unwanted sexual attention such as cat-calling, wolf-whistling, groping, flashing in any public space including public transport or on a street. [The Law Commission defines public sexual harassment as harassment that was sexual, had the intent to degrade or humiliate, and that took place in public, the Guardian reports.]

What are the main challenges the campaign's faced?

Unfortunately, I have come across people trivialising the issue, in terms of "what's wrong with wolf-whistling" etc. We use the term public sexual harassment and that encompasses a lot of behaviours that are typically dismissed as minor but can also escalate to more dangerous behaviours.

I've seen some articles dismissing it by saying people are being too sensitive. We know the impact that it has on victims' mental health when they are unable to access any support. When people are harassed, people change their behaviour because they're so used to being harassed, and that's what the reality is.

We have had to emphasise that this type of harassment is not a result of what people wear, or if they walk alone at night — we should all be free to travel in whichever route we choose, without having a fear of being harassed.

Another argument we’ve seen against the proposed Bill is that if we criminalise public sexual harassment, it would create too much additional workload for the police and that there's already legislation to cover this behaviour, which is just simply not true. In reality, current legislation is piecemeal and not fit for purpose.

While sexual harassment in the workplace is unlawful under civil law under the Equality Act 2010, our analysis has uncovered legislative gaps around public sexual harassment. No law has been enacted specifically to prevent and prosecute public sexual harassment and therefore this form of seriously harmful conduct falls through the legal cracks.

I’ve found that policy-makers sometimes lack knowledge of the subject, which is why we're trying to help and advise them. We have done all the research and they need to come alongside us and other groups that are working within the "violence against women" sector.

We need action NOW. Not more talking & consultations. The govt needs to pledge to make sexual harassment a crime. @OurStreetsNow@DexterDiasQChttps://t.co/4wR47DV85p

— Dr Charlotte Proudman (@DrProudman) December 7, 2021

What have the reactions from the British public been like?

In general, a lot of people are surprised that public sexual harassment isn’t already illegal. Why wouldn't it be a crime? People are shocked that you can get fined for littering but not for shouting obscene things at schoolgirls from a passing car.

However, some people, mainly over social media, have made comments along the lines of, “if I want to compliment somebody, what's wrong with that? It's not that creepy. I'm just trying to be nice.” Others have suggested that it means over-policing.

We have had people calling us “silly little girls” just for standing up for what we believe in and been sent some threatening messages on social media — which is a testament to why we need to keep campaigning.

But on the whole, the general sentiment is that public sexual harassment should be a crime. Nobody should have to go through it. People would feel a lot safer if they knew that there was an avenue to report this behaviour, and that could stop it from happening as often.

It’s not about going around locking up everybody who shouts at somebody — instead it’s about there being some negative consequence, like the fine you get for littering. Changing the law would have some cultural implications too, just by raising awareness of the issue. The fact that the conversation has been so publicised now means more people know about it, and when to call it out. So it's about changing the culture and our laws reflect our culture.

How would you decribe the seriousness of public sexual harassment to people who dismiss the issue as trivial?

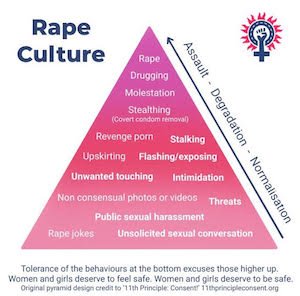

The best way to describe the magnitude of public sexual harassment is this concept of the pyramid of gender-based violence. At the bottom of the pyramid are things that are upholding worse behaviours further up.

Behaviours like public sexual harassment, for example cat-calling, help to normalise misogyny and as you go further up, you get more violent assault and stalking, then femicide, murder, and rape. So those behaviours on the bottom, although they might seem minor in comparison, are perpetuating a violent force that eventually can escalate to those more extreme violent behaviours.

If you start taking out the bricks at the bottom then you can really tackle the issues, and the more you challenge that behaviour, the more people realise it's not acceptable to sexually objectify women without their consent.

Do you worry that if public sexual harasment is criminalised it will be underreported, as violence against women often is?

Yes, definitely, that's why the campaign is made up of so many different aspects because we understand that changing the law alone is not enough. We have to go for educational and cultural changes as well, for example by raising awareness and workshops in schools.

It's not about locking up everybody who's harassing somebody, it's about showing that the behaviour is unacceptable and letting people know how it makes them feel. Often people don't think about the anxiety that being on the receiving end of a so-called “harmless” comment causes. But the more that we talk about it, the more people are aware. I think that's how things will change.

What are the next steps for the campaign to change the law?

We were quite grateful that it's been recognised by the Law Commission, as a great first step to realising that change actually needs to happen.

We’re making progress, but we need 500,000 or more signatures on our petition [which you can sign with Global Citizen here] to be able to back up our argument when taking it into parliament.

We need the government to put their money where their mouth is and really invest in the cause. I want them to do it in a meaningful way by getting behind the educational campaign, helping with funding and resources, and working in tandem with us and other organisations like Reclaim the Streets.

What advice would you give to other young people who want to get involved in activism?

My advice would be just to go for it. Starting your own campaign from scratch isn’t easy and it can be intimidating but it is achievable. If you believe in your cause, and you're passionate about it, then other people will definitely get on board with you.

Be bold and keep standing up for what you believe in, but do not lose sight of what your original goal is. Sadly, there's a lot of things wrong with the world but there's definitely something that you can do about that.

Women’s rights are human rights — and they must be promoted and protected. This 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, from Nov. 25 to Dec. 10, we’re asking Global Citizens to join us for our #16Days Challenge, to take a simple action each day that will help you learn more about women’s rights, bodily autonomy, and gender violence online.

You’ll start important conversations with your loved ones, advocate on social media for women’s and girls’ right to their own bodies, support women-owned businesses in your community, sign petitions to support bodily autonomy, and more. Find out more about the #16Days Challenge and start taking action here.