Hunger is not inevitable. It is not too big of a problem to solve. In fact, it has improved dramatically in just the last 30 years. Indeed, not only have 193 countries committed to ending hunger through the Global Goals, international reach institutions like the World Bank and United Nations have determined ending extreme poverty and hunger by the year 2030 is an ambitious, yet achievable, goal in need of transformational policies that address inequality and boost shared prosperity. Ending hunger by 2030 is possible. Here’s why:

1) Contrary to popular belief, world hunger has, on the whole, improved

Since 1990-92, the number of hungry people in the world has declined by 216 million people, despite an increase in world population of two billion. That’s 7 million less than just a year ago.

2) Many countries have greatly reduced or eliminated hunger in just 25 years

Vietnam reduced hunger from 45% in 1990-1992 to 13% in 2012-14.

China reduced child stunting–having inadequate height for one’s age—from 32% in 1990 to 8% in 2010.

Brazil virtually eliminated hunger (between 2000-02 and 2004-06 the undernourishment rate fell by half from 10.7% to below 5%) and reduced child stunting from 19% in 1989 to 7% in 2007.

Thailand reduced hunger from 36% in 1990 to about 7% in 2012-14.

3) The Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of cutting hunger was actually achieved by the majority of countries

Seventy-two out of the 129 of the countries monitored achieved the target of halving the prevalence of undernourishment by 2015, with developing regions as a whole missing the target by a small margin. In addition, 29 countries have met the more ambitious goal laid out at the World Food Summit in 1996, when governments committed to cutting in half the absolute number of undernourished people by 2015.

4) Child nutrition and health—key to ending hunger—are improving

There has been a 40% decrease in child stunting in the past 25 years.

5) Research institutions have determined ending extreme poverty is possible by 2030

And because poverty and hunger are inextricably linked, this has a direct impact on ending hunger. According to World Bank scenarios, if we assume a per capita growth of 4 percent in each developing country (which has been the average growth rate of developing countries as a whole from 2000 to 2010) as well as unchanged income distribution (equivalent to the average for developing countries as a whole from 2000 to 2010), it is possible to bring global poverty to 3% of the world’s population – what is viewed as a statistical end to poverty – by 2030.

6) The world has committed to ending hunger through the Global Goals

More than ever, investing in nutrition and the end of hunger is seen as a key development priority. Global Goal #2, the “Zero Hunger” goal, calls for ending hunger and improving nutrition by 2030, and 193 have committed to making this happen.

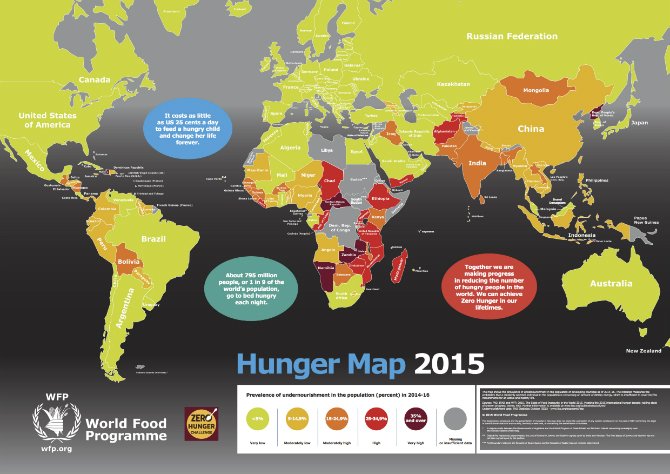

While these facts demonstrate tremendous progress, ending hunger by 2030 remains a colossal task. An unacceptable 795 million people – one in nine people – live in chronic hunger. Governments and the global community must allocate sufficient resources and pursue policies and investments that promote equality while enlisting full participation at the grassroots level. Indeed, inclusive growth – growth that provides opportunities for those with few assets, skills and opportunities – improves the incomes and livelihoods of the poor, and is effective in the fight against hunger and malnutrition.

Central to ending hunger are programs and policies that call for enhancing the power and capacity of communities to take charge of their own development. Only when communities are not “bystanders” but “active citizens” in their own development and viewed as the “solution” rather than the “problem” can the end of hunger be achieved.

This article was contributed in support of the Hunger Project. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of each of the partners of Global Citizen.