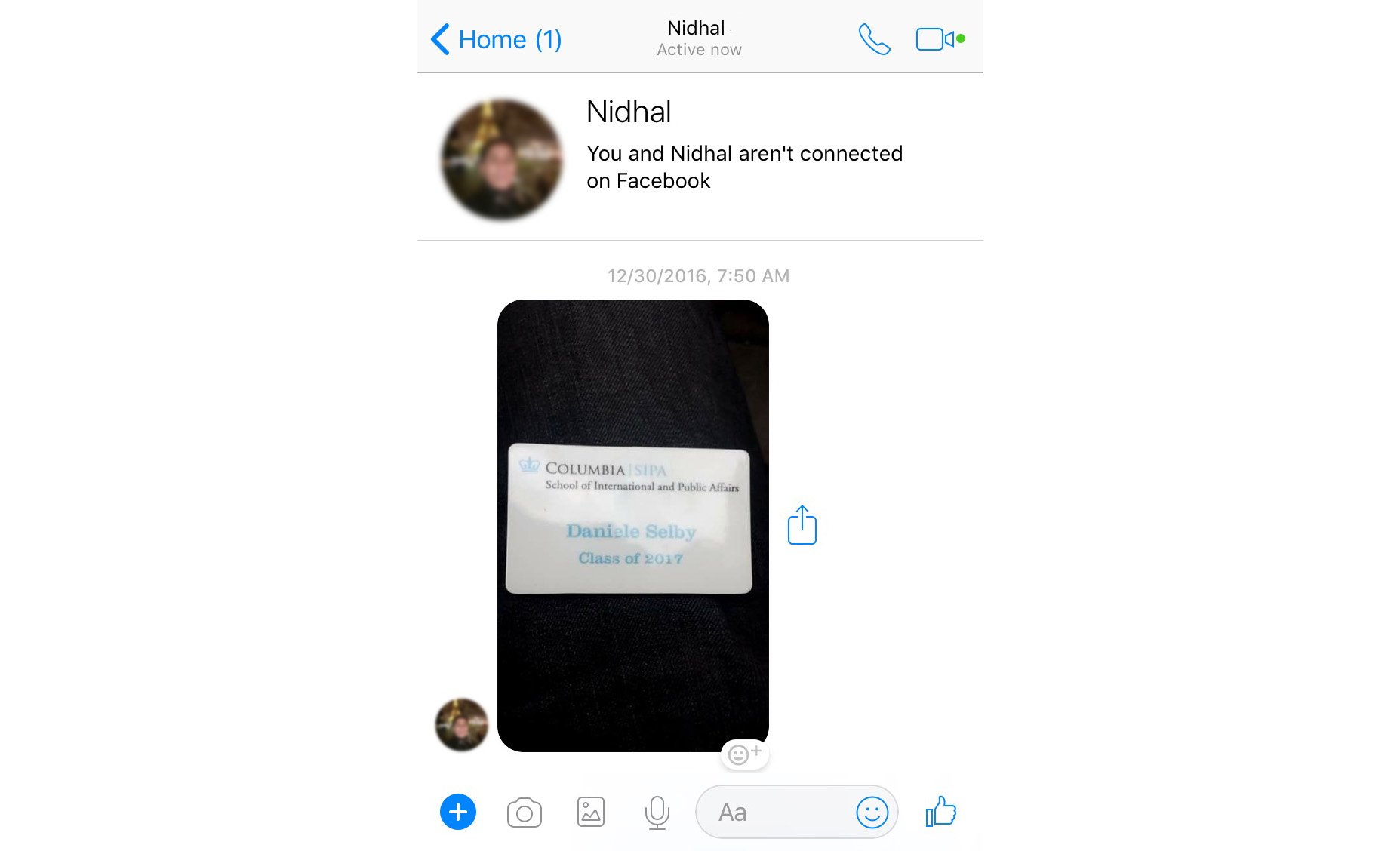

This spring I found a message in that mysterious part of my Facebook inbox where spam and inappropriate messages from strangers typically go. The message, from a Tunisian man named Nidhal, had no text, just a photo of the name tag I was given during my graduate school orientation.

Having recently been hacked and seeing that Nidhal worked in the tech industry, I figured it was safer to ignore the message, but for months I wondered how this stranger had ended up with the name tag I’d assumed was still somewhere in my apartment.

The best explanation I could come up with was that the tag had been in the Columbia University-branded backpack they gave us at orientation, which I’d donated to Housing Works, a non-profit organization focused on fighting AIDS and homelessness that has several thrift stores in New York City.

I had given the backpack, with several bags of clothing, to Housing Works after channeling my inner-Marie Kondo and purging my closets last Thanksgiving, something I try to do twice a year.

And because I don’t want to contribute to the millions of clothes that already end up in landfills every year, I typically donate any used items in good condition I have to charities or thrift stores. Personally, I like to donating to Housing Works because I want to support their work.

Read more: New Report Documents Staggering Toll of 'Wasteful, Polluting' Fast Fashion

I’ve always thought that taking my used clothing to a thrift store was a net positive — the charity that runs the store earns money from my donation, someone gets a new outfit, and my clothes don’t end up as waste.

But, in a strange turn of events, I was recently confronted with the potential impact of my donations — and it wasn’t all positive.

Though I’d given a lot of thought to where I’m willing to donate my used goods — only to organization’s whose missions I fully support — I had never really thought about where my stuff went after I took it there.

The answer, as it turns out, is Tunisia.

But, short of someone walking into a Housing Works thrift store in New York City, buying it, and taking it back to Tunisia, I still had no idea how my bag ended up across the Atlantic.

After arming myself with anti-virus and turning on every possible cyber protection option, I gave into my curiosity and responded.

And as it turned out, I was mostly right.

How My Bag Became Nidhal's Bag

Nidhal had found my name tag inside a backpack he had purchased — my orientation bag.

But he hadn’t bought it in New York, he’d bought it in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, from a store that sells second-hand goods. And far from wanting to hack me, he had reached out because he was also curious about how my bag ended up in Tunisia.

Very quickly we were able to piece together what had probably happened.

A computer engineer, Nidhal was looking for a good bag that he could use for work. He bought my backpack for 30 Tunisian dinar (about $12) from a “fripe” — literally meaning “crumple” in French, but “thrift,” colloquially — shop in an area of Tunis called Hafsia.

These stores, he said, are stocked with second-hand goods purchased from wholesalers who either import the goods, or buy the used good from importers in bulk.

As far as Nidhal and I could tell, Housing Works had decided not to sell my bag in its stores, and instead had sold it to a used goods exporter, or clothing salvager. These are companies that buy used clothing and footwear in bulk, then sort and bundle the items to be shipped to countries like Guatemala, Rwanda, Kenya, and Tunisia.

From there my backpack would have crossed the Atlantic in a shipping container, ultimately making its way to a fripe shop in Hafsia in Tunis. In all likelihood, my bag was sold through Trans-Americas Trading Co., a New Jersey-based company that processes 80,000 pounds of clothing, much of it donated in New York City, Newsweek reported.

Though Nidhal and I were pretty sure we’d figured out how my bag ended up in Tunisia, it was surprisingly difficult to confirm our theory with Housing Works.

During the course of weeks of reporting, it became clear that the resale of used goods from developed countries to developing countries has, in recent years, become controversial.

And that, Nidhal and I decided, was worth trying to understand.

Your Donations Are A Multi-Billion Dollar Business

The global second-hand clothing industry is worth about $3.7 billion, according to the Guardian. And while it offers people in developed countries an alternative to throwing clothes out and sending them to landfills, experts and politicians have said the used clothing business impedes developing countries’ efforts to build up and sustain local textile and clothing industries.

Charities like Housing Works and Goodwill receive such a large quantity of used clothing, in varying states of repair, that they cannot possibly sell all of it in their thrift store locations.

“We do not sell ‘surplus’ donations, but we do sort our donations and pull out items that we do not deem a certain quality to sell. This could include rags, used towels, undergarments or severely stained items,” Katherine Oakes, Housing Work’s Marketing and Communications Manager, told me via email. Though it is worth noting that my never-used bag was none of those things.

Housing Works told Newsweek that it sells about 40% of the donations it receives in its thrift stores — but what happens to the other 60%?

“These items are then bundled and sold to a variety of vendors, not necessarily exporters,” Oakes said in an email.

But the New York Times reported that the items charities reject are often sold for a fraction of their retail price to wholesale companies, like the Trans-Americas Trading Co., which then export them from North America and Europe primarily to African countries. So while Oakes said that my bag wasn’t necessarily sold to an export, it is still possible — if not likely — that it was.

Read more: Does Recycling Your Clothes Actually Make a Difference?

The US is the largest exporter of used clothing and worn goods in the world, according to UN data. It not only sends massive quantities of clothing to African nations, but also exports millions of dollars worth of second-hand clothing to Chile, Guatemala, and Mexico. In fact, when East African nations proposed a ban on second-hand clothing imports earlier this year, the US threatened to review trade agreements with those countries, according to the New York Times.

Most of the clothing donated globally — 70%, the non-profit organization Oxfam told the Guardian — eventually finds its way to Africa. As a whole, the continent of Africa imports about $1.2 billion worth of worn clothing and shoes a year, according to the Overseas Development Institute, a think tank.

In Tunisia, half of all clothes sold are second-hand, France 24 reported, and in 2016 alone the North African nation imported more than 170,000 tons of worn clothing and other items, according to the UN. Nidhal said that many Tunisian people buy their clothes, shoes, and accessories from second-hand stores because they are often of a better quality than inexpensive, new clothes available on the market.

He explained that while he could have bought a new bag in Tunisia for less than half the price of my second-hand bag, such a bag would likely be a poorer quality, hence the appeal of buying second-hand goods.

These goods, although second-hand, are considered to be better quality than new items sold at local shops, which are generally made in China and perceived to be imitations, Nidhal said. Another major draw of the stores is their variety. Nidhal said Tunisia’s fripe shops sell used everything from unbranded clothes to “fast fashion” labels like H&M and Forever 21, and even goods from luxury brands like Chanel, which don’t even have stores in the country yet.

So second-hand clothing in Tunisia is not just for the poor, he explained. The same is true in Rwanda where most middle class people mix new and second-hand clothes, Quartz reported.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Selling second-hand clothing, either at the wholesale or consumer level, can be a good business, which adds another layer of complexity to the controversy around the second-hand merchandise industry. For someone like Chokri Chniti, owner of Stife Company, selling used clothing offered a way out of poverty, according to France 24.

Though success in the business is far from certain. In Mozambique, some second-hand clothing sellers even call the industry a “totobola,” meaning “lottery,” according to the Guardian.

Second-hand goods are sorted and bundled by quality and sold by weight. A bundle of first rate clothing — meaning clothing that is of a good quality, branded, and in good repair — sells for about 15 dinar (roughly $6) per kilogram, while a 1kg bundle of third rate goods sells for 1.5 to 2 dinar (less than $1), Mongi Lafeti, the head of sorting operations for the second-hand goods exporter Stife Company, told France 24.

Sellers in Tunisia, and most other African countries importing used clothes, buy the merchandise from wholesalers sight unseen, a la “Storage Wars,” so they never actually know what they’ll be getting.

Still, the new trade sector has made clothing more affordable for many people and created jobs, according to the Huffington Post, but it’s not without major drawbacks.

The industry relies on imports from Western nations that, ironically, rely on exports from countries like Tunisia — which produces and exports textiles and clothing for brands like Diesel jeans and luxury brand Longchamp.

And while second-hand shirts “may be quite cheap for someone to buy...it would be better if that person could buy a locally manufactured t-shirt, so the money stays within the economy and that helps generate jobs," Andrew Brooks, the author of “Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-hand Clothes,” told CNN.

Over the last few decades, employment in the textile and clothing industries in several African countries has fallen — 85% of Kenya’s textile plants have closed since the 90s, Reuters reported — as the second-hand merchandise industry has burgeoned, according to CNN.

In the last year, several East African countries — including Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Tanzania — have aimed to reduce used clothing and footwear imports, and announced plans to ban them all together by 2019, the New York Times reported. These countries hope these new measures will give domestic clothing and textile industries a chance to develop and wean their reliance on imported used goods.

Should I Stop Donating My Stuff Then?

No. This shouldn't necessarily dissuade anyone from donating their used clothes to charities, and here’s why.

For its part, the money Housing Works makes from selling donated items to wholesale exports still goes toward supporting its mission of ending AIDS and homelessness.

“When we sell off unusable donations those funds still directly help us to provide lifesaving services to people living with HIV/AIDS and homelessness such as healthcare and housing,” Oakes said.

And donating my clothes instead of throwing them out still helps to put a dent, however miniscule, in the millions of tons of clothing that end up in landfills every year.

If everyone suddenly stopped donating their clothes to charities, or charities abruptly ceased selling used clothes to wholesale exporters, the second-hand clothing and footwear industry in these African countries would be strangled, causing many people to lose their livelihoods and robbing others of a cheap clothing option.

Read more: How to Make Sure Donated Goods Are Helping, Not Hurting, After a Crisis

Critics of the proposed bans on imported second-hand goods are concerned that the policies would end up stripping people of their livelihoods, the Huffington Post reported.

Experts have also said that local textile industries might not yet be developed enough to produce clothing to meet local demand on their own, so banning the sale of second-hand clothing would drive up the cost of domestically produced goods, or result in poorly produced goods forcing people to ultimately spend more money on clothing.

There are other ways these governments can incentivize the growth of these industries, and sustainably grow domestic textile and clothing production, the Overseas Development Institute said.

So What Can I Do?

Rather than never donating your used clothes to charity again, we, as consumers, can do our part by being more conscious about what and how much we buy.

If we bought less stuff, we’d have fewer clothes to donate at the end of every season.

And instead of buying cheap, “fast fashion,” we can support budding industries by purchasing goods produced there, which can help those economies grow and become sustainable. However, to be truly sustainable those industries need to meet a locally-driven demand, not just the demand of well-intentioned overseas markets.

Read more: Want to Be an Ethical Shopper? There's an App for That

I will probably continue to bring my used clothes to Housing Works, but now I’ll do so with the knowledge that the journey of my stuff doesn’t end there. It’s unlikely that someone in the same community as me, even the same country as me will end up using my donated goods.

But someone will, hopefully, get use out of them and keep them out of landfills.

Regardless of how my bag made its way to Tunisia, Nidhal said he’s now getting great use out of it in Paris, France.