Today, economic strife continues to send shockwaves of humanitarian need across Afghanistan, and its health care sector has suffered more than any other.

After decades of relying on international aid, the Taliban’s overthrow of the US-backed Afghan government caused key humanitarian providers to quietly leave the country or vastly reduce their footprints. When the US and coalition partners withdrew from the country in August 2021, much of Afghanistan’s aid went with them.

In May, the United Nations estimated that almost 20 million people in the country were facing acute hunger, and that 3.5 million children were in need of nutritional support. In just 10 months, 15 years of economic growth have been lost, the UN said, with the country’s economy contracting some 30 to 40%. The UN noted in fall of 2021 that 97% of the population could be living below the poverty line by mid-2022. In March this year, the organization said that “that number is being reached faster than anticipated.”

Even before the Taliban takeover of the country, and during a US troop drawdown, donors had already begun pulling support from Afghanistan. The freezing of foreign aid from big donors such as the World Bank has forced many hospitals to close.

Afghanistan is one of the least medically-equipped countries in the world, with just 3 doctors per 10,000 people. The health care shortfalls are particularly pronounced in rural areas, where 85% of the population live below the poverty line and infection and malnutrition have long been widespread.

Now, economic instability has resulted in numerous vaccination gaps, and Afghanistan’s most vulnerable populations are facing a resurgence of diseases that were nearly eradicated.

Health Care Workers Act as Lifelines to Rural Communities

Mornings here are the busiest, 45-year-old Nazifa Kamawal, told Global Citizen, raising her voice to compete with the protesting cries of 9-month-old Bibi Zeinab, who had just received her measles vaccination at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul.

Nazifa Kamawal vaccinates 9-month-old Bibi Zeinab at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul, Afghanistan.

Nazifa Kamawal vaccinates 9-month-old Bibi Zeinab at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul, Afghanistan.

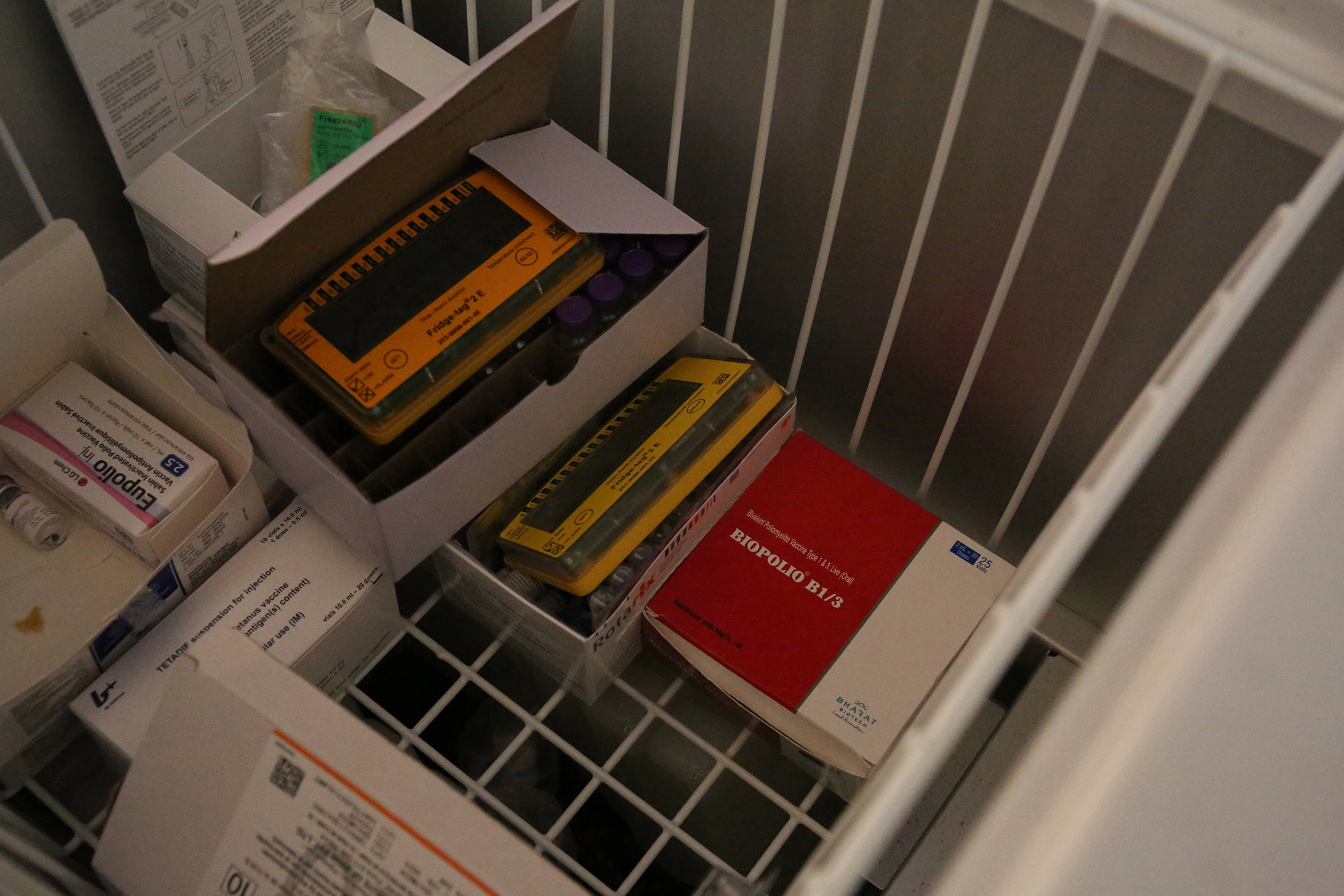

The health center was established 40 years ago. Today, supported by UNICEF, it offers 10 vaccines through its Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) for viruses including tuberculosis, hepatitis B, pentavalent, measles, rotavirus, tetanus and diphtheria, and polio.

Kamawal has been working in health care since 2000, and at this clinic for 15 years.

“We have power and refrigerators to keep the vaccines cold and we are vaccinating 60 people every day. But this is not the case everywhere in Afghanistan,” she explained, settling into the black leather chair behind her desk. She says that some mothers, who moved to the capital and were not previously reached by vaccination campaigns due to living far from the district centers, are now agreeing to get their own vaccinations alongside their children.

That same day, for instance, 40-year-old Shiva brought her daughter into the clinic for her vaccinations with Kamawal and also agreed to get a tetanus vaccination herself.

But far from this health center in the capital, small community clinics staffed by one or two nurses cater to populations spread over hundreds of kilometers.

Most people living in Afghanistan’s rural reaches cannot afford to travel to larger hospitals in the provincial centers, so small, local medical facilities are a lifeline. But these medical staff are working with the bare minimum of equipment, medicine, and other resources. And the staff numbers continue to decrease.

“These facilities just don’t have access to the vaccines or the facilities to store them correctly,” Kamawal said. “The only way to reach people is through mobile teams going door to door.”

Kamawal was part of a mobile vaccination team before joining the fixed staff at the Shah Shaheed clinic, and says that while the clinic in the capital has seen an increasing number of patients over the last year, the hurdles for mobile teams working in Afghanistan's rural provinces far outpace the clinic’s.

45-year-old Nazifa Kamawal at her desk at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul. Kamawal has been working in health care since 2000 and at this clinic for 15 years.

45-year-old Nazifa Kamawal at her desk at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul. Kamawal has been working in health care since 2000 and at this clinic for 15 years.

“We had a campaign team go to villages to talk to the elders, the mullah, or the imam and the heads of the families to explain why vaccinations are important. Then we would go to their families to talk to them and convince them that vaccinations are good for them. If they agreed, we set a date to come back,” she explains.

“We would also come two days before to remind them again and explain the vaccine again and the side effects, such as fever, so they are not scared, because some people were getting scared after being vaccinated, saying, 'Why did you make me sick?'”

“After the vaccination we tell them, we will come back for their second dose. And again, two days before the vaccination, we visit them again to say, 'Please be ready, we are coming here in two days' … It’s a whole process. And going door to door is difficult because people just don’t trust us,” she said.

Parental refusal remains a challenge, she says. Some families hold deep myths, at times related to religion, particularly in southern Afghanistan where some remain adamantly opposed to vaccinating their children, despite interventions by health workers and community elders.

“In these areas, the knowledge of vaccinations is still low, partly because vaccinators have not been to these areas before,” Kamawal said. “In the past, the conflict affected our access. Security was an issue for our mobile teams and so there are still communities that were never reached.”

But a larger issue remains misinformation around the vaccines. Kamawal said that people are afraid of the impact the vaccines will have on their health, or else concerned that they are foreign-made and designed to make children sick or cause pregnancy issues.

(L) Sakina and her daughter Aliya wait for their vaccinations at the Shah Shaheed health facility. (C) 9-month-old Bibi Zeinab sits with her father and brother. (R) 30-year-old Rahima has brought her daughter, Shahzadi, for her vaccinations.

(L) Sakina and her daughter Aliya wait for their vaccinations at the Shah Shaheed health facility. (C) 9-month-old Bibi Zeinab sits with her father and brother. (R) 30-year-old Rahima has brought her daughter, Shahzadi, for her vaccinations.

“In the cities, people are more educated and there has been increased awareness on the community level, of the importance of vaccination, but this fear and distrust in rural areas hasn’t changed. Not in my 15 years of doing this work.”

Kamawal says that in order for all children to be vaccinated, efforts are still needed to dispel myths and rumors around vaccines to convince families who are afraid of immunization.

The Taliban Banned Vaccine Delivery

Afghanistan has seen four decades of war and subsequent political, religious, and military conflict challenges have prevented health care workers from doing their jobs.

Polio immunization programs have been particularly hard hit. The national ban on door-to-door vaccinations since May 2018 by the Taliban led to 3.4 million children being missed in every round of a national immunization day, according to Merajn Rasekh, a communication consultant for the polio eradication program in Afghanistan’s Ministry of Public Health.

Baby Murat is 45 days old and will be receiving his polio vaccination at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul. He is 1 of nearly 10 million children under 5 in Afghanistan who remain vulnerable to this disease.

Baby Murat is 45 days old and will be receiving his polio vaccination at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul. He is 1 of nearly 10 million children under 5 in Afghanistan who remain vulnerable to this disease.

The situation deteriorated further when the Taliban imposed a nationwide ban on all vaccinations in April 2019 for a period of five months.

In neighboring Pakistan, efforts to eliminate polio were seriously undermined a decade ago when the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) conducted a widely-criticized fake vaccination campaign as part of its intelligence gathering operations on the whereabouts of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad.

Following the disclosure of the CIA mission, the Taliban launched an anti-vaccine propaganda campaign on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Polio teams were attacked in both countries by the militants, and several field workers were killed. In Pakistan, over 100 on-duty polio workers were killed between 2012 and 2017 alone.

On March 30, 2021, in Afghanistan, three women were gunned down in two separate attacks as they carried out door-to-door vaccinations in the eastern city of Jalalabad. Less than three months later, in June, five polio vaccination workers were killed in five more coordinated attacks in Jalalabad while they were providing door-to-door vaccinations. In February this year, eight polio vaccinators were killed in separate attacks in Afghanistan’s northern provinces of Takhar and Kunduz.

COVID-19 Set Back the Country’s Immunization Efforts

A major new driver of Afghanistan’s polio and measles outbreaks was the pause in vaccinations for several months in 2020 in a bid to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

According to UNICEF, the disruption in immunization left a total of 50 million children without their polio vaccine in Afghanistan and Pakistan, with polio campaigns and other essential health services disrupted between February and August 2020, creating additional immunity gaps, with only 15% of the expected coverage reached for the year.

“Due to both COVID-19 and insecurity, we couldn't launch about five rounds of polio vaccination campaigns in Afghanistan, which have resulted in an increase of polio cases in the country,” Rasekh told Global Citizen.

Measles Cases Are on the Rise

Measles cases have been rising sharply since July 2021. In the first six months of this year, there were 59,662 reported cases in Afghanistan, including 351 deaths — compared with 156 confirmed deaths in all of 2021. Last year, more than 97% of those deaths were among children under 5. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported in March this year that one of its projects in Herat province was seeing two children dying from measles each day.

Coverage of the measles vaccination in Afghanistan has stalled at 66% rather than reaching the recommended 95%.

Kamawal says the measles epidemic is a big issue because of the paused campaigns. The health care worker says that the next immunization campaign will start again in two weeks and will be for children up to 10 years old, but she feels that it is not likely to reach its intended numbers. Due to the vaccine’s cold chain requirement, it does not travel well, and many people will be unable to come to provincial and district centers to receive it.

Polio Cannot Be Eradicated Without Improved Vaccine Access

Rahima's daughter, Shahzadi, is vaccinated at the Shah Shaheed health facility. She is Rahima's fourth child to be vaccinated there.

Rahima's daughter, Shahzadi, is vaccinated at the Shah Shaheed health facility. She is Rahima's fourth child to be vaccinated there.

Like the measles campaign, polio immunization campaigns were suspended amid the COVID-19 pandemic between February 2020 and August 2020, and again during the first six months of 2021.

Rasekh said last year that an absence of vaccine campaigns allowed wild poliovirus and vaccine-derived cases to encroach on previously polio-free areas of Afghanistan.

Today, in more than 70% of the areas covered, polio vaccines are given door to door by polio health care workers. The polio vaccine is administered orally (OPV) or through a shot (IPV). OPV is used more commonly in Afghanistan as it is less expensive and does not require needles or need to be kept cold. The oral vaccine contains a live version of the virus, which can mutate to become a variant form — vaccine-derived polio. While you cannot get polio from the vaccine itself, vaccine-derived polio can spread through a community with low vaccination rates, leading to circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) reported 56 wild poliovirus cases in Afghanistan in 2020, compared to 29 total cases in 2019. In September 2021, the WHO had reported seven cases of wild polio and 43 cases of cVDPV2.

Traditionally, the virus thrives in late summer in Afghanistan, and its spread is being helped along by increased population movements as a result of displacement amid the Taliban takeover of the country on August 15, 2021, according to Dr. Hamid Jafari, director of polio eradication, WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region.

In 2021, the GPEI was facing a shortfall due to a nearly $3 billion drop in pledged international aid to Afghanistan compared with the previous four year period, on top of losing nearly all its UK funding, (the country went from contributing £110 million last year to just £5 million this year).

Hope for the Future

On Oct. 18, 2021, the dialogue between the UN and Taliban leadership showed some hope. The WHO announced that door-to-door polio vaccination would recommence across Afghanistan on Nov. 8 last year — the first campaign in over three years to attempt to reach all children in Afghanistan, including more than 3.3 million children in some parts of the country who have previously remained inaccessible to vaccination campaigns.

Another immunization campaign was also just launched on July 25, an Afghanistan UNICEF representative told Global Citizen, with the vaccinators going door to door across the country.

Nazifa Kamawal, 45, poses for a portrait at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul.

Nazifa Kamawal, 45, poses for a portrait at the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul.

“Security is no longer a problem,'' Kamawal said. “Now it's more safe and secure for our mobile teams than before.”

In July, UNICEF told Global Citizen that Afghanistan is no longer facing any funding cuts for the polio program and noted that while the change in authorities last year brought challenges, it also presented an opportunity to improve access to areas UNICEF could not reach before, and ultimately vaccinate more children.

Despite the hurdles, the efforts of the country’s health care workforce are remarkable, as they work hard to ensure the greatest number of people are vaccinated.

“Fifteen years ago, we had 50 patients a day,” Kamawal said. “Now we have 60 a day … Yes, there aren't that many more. But at least people are still coming to us. That is success.”

Not much has changed for the city health centers, Kamawal concedes. And not much has changed for the vaccinations in rural areas.

“People are still thinking in the same way they were before. Now, maybe with more access, we will be able to reach these communities more,” she said. “But the reality rests on the economic situation. Most mothers will still struggle to bring their children for vaccination in the city center in hospitals and health facilities, so mobile teams are still the best solution, unless more health facilities are built in the provinces and rural areas.”

40-year-old Shiva brought her daughter into the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul for her vaccinations with Kamawal, but then also agreed to get a tetanus vaccination herself.

40-year-old Shiva brought her daughter into the Shah Shaheed health facility in central Kabul for her vaccinations with Kamawal, but then also agreed to get a tetanus vaccination herself.

In some ways, much has changed in the last 20 years in Afghanistan. In other ways, very little has.

While Kamawal prepares Shiva for the vaccination, she notes what everyone in Afghanistan already knows: The capacity gap between the cities and the provinces is Afghanistan’s biggest barrier to accessing equitable health care.

“It is those in the rural areas who always suffer the most,” she said.

Editor's note on Dec. 2, 2022: An earlier version of this story referenced a widely-criticized fake polio campaign, but the campaign in question was a fake hepatitis B vaccination program.

The End of the Line series looks at the amazing ways in which the world is reaching the “last mile” with vaccines. It covers what it’s like to deliver vaccines in war-torn settings, as well as hard-to-reach areas, while highlighting the role of community health workers and the logistics involved in vaccine delivery.

Disclosure: This series was made possible with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Each piece was produced with full editorial independence.