When Edward Galvan found out he was exposed to HIV, it was one of the scariest moments of his life.

“I was mortified,” Galvan told Global Citizen. “I was hesitant to go to the doctor because what if, what if…”

Eventually, stress and depression made Galvan so physically ill he had no other option but to seek medical attention. He tested negative — a massive relief.

Since that scare a decade ago, Galvan has seen HIV take a toll on several friends who have contracted the virus.

“They have this anger, this sadness — all these negative emotions and it's understandable … with all the stigma that's out there in society and how people shun those who are positive,” Galvan said.

When Galvan, who lives in Chino Hills, California, learned a local clinic was seeking participants for an HIV clinical trial, he jumped at the opportunity “to do something proactive to help out with the [LGBTQ] community.”

Edward Galvan poses for a portrait in Chino Hills, Calif., on Nov. 28, 2022.

Edward Galvan poses for a portrait in Chino Hills, Calif., on Nov. 28, 2022.

The study, which only enrolls participants who are HIV negative, is part of the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN), a network of clinics around the world working to develop a vaccine for the virus.

The Emergence of HIV

In 1981, doctors identified the first known case of HIV in the US, which was traced back to chimpanzees in Central Africa. Since then, over 40 million people have died as a result of the virus. In 2021 alone, approximately 1.5 million people contracted HIV worldwide. Another 650,000 people died from HIV-related causes.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) destroys and impairs immune cells in the body. The virus spreads through the exchange of bodily fluids from an infected person, such as blood, semen, and vaginal excretions. The most advanced stage of the virus is acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The virus, which in its initial years was primarily detected amongst queer men, was widely labeled as a “gay disease” and even “gay cancer.” Some researchers cite discrimination and homophobia as causes of HIV. For example, one study suggests the “cultural perception of gay and bisexual males as less masculine may lead to their assertions of masculinity through engagement in unprotected sexual behaviors.”

According to UN AIDS, in addition to men who have sex with men, other at-risk groups for HIV include female sex workers and their clients, transgender people, and injecting drug users.

Developing HIV Vaccine Candidates

Dr. Larry Corey, an expert in virology, immunology, and vaccine development, is one of the most prominent doctors working to find solutions to HIV. In the early 80s, he led the AIDS Clinical Trials Group, which proved combination antiretroviral treatments (ARVs) could control HIV.

Corey calls the use of ARV drugs “one of the big discoveries in medicine in the last 50 years.” As a doctor, he went from seeing HIV positive patients dying within a year of contracting the virus to living up to an additional “30 or 40 years while taking regular medication” — and the medication’s effectiveness has improved since then, he said.

Nurse Nomautanda Siduna gives hand sanitizer and antiretroviral drugs to a patient in Ngodwana, South Africa, July 2, 2020.

Nurse Nomautanda Siduna gives hand sanitizer and antiretroviral drugs to a patient in Ngodwana, South Africa, July 2, 2020.

When it comes to curbing the spread of HIV, Corey says a vaccine is necessary.

“COVID has taught us that when you want to control a virus on a population basis, from a disease point of view, you need a vaccine,” he told Global Citizen.

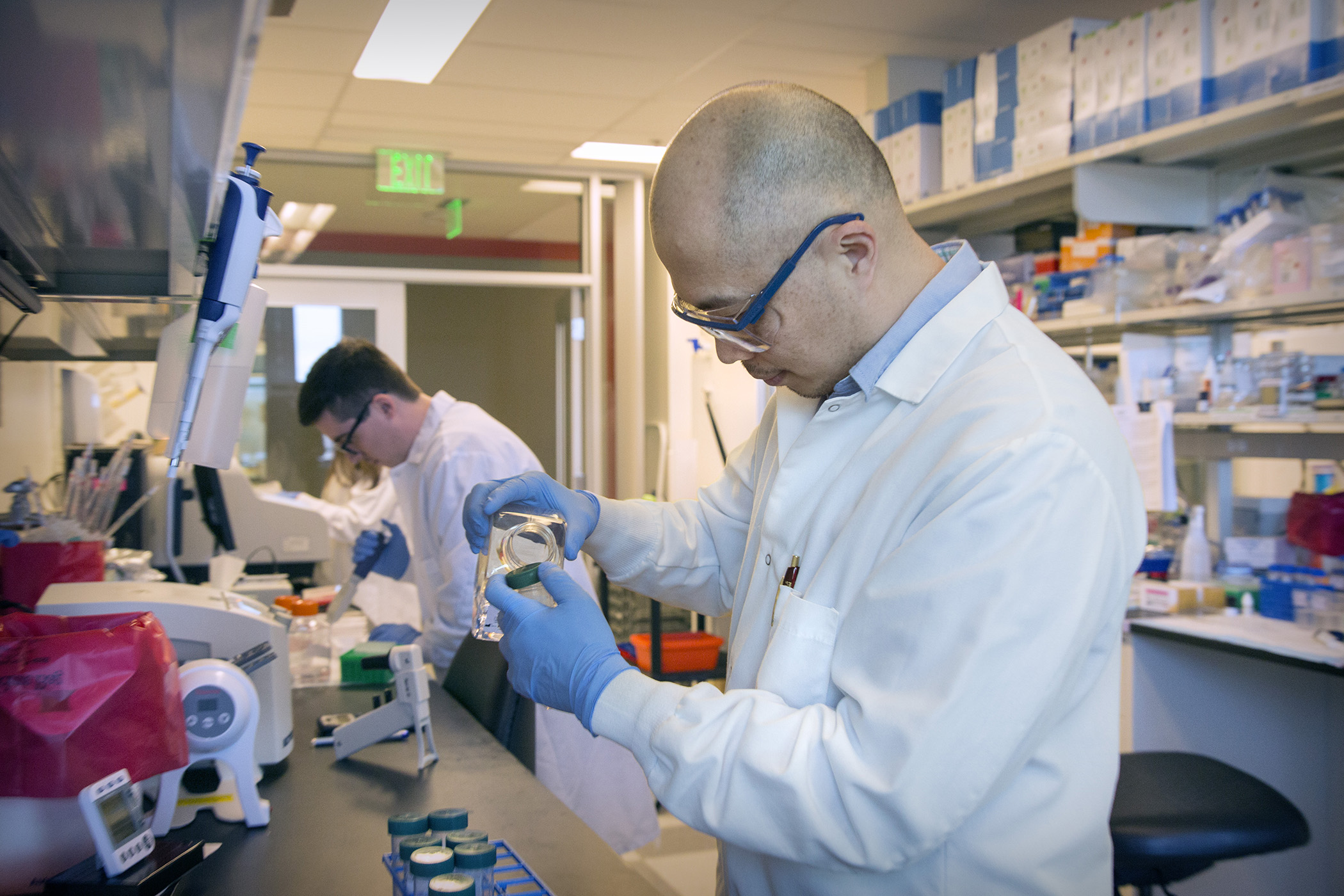

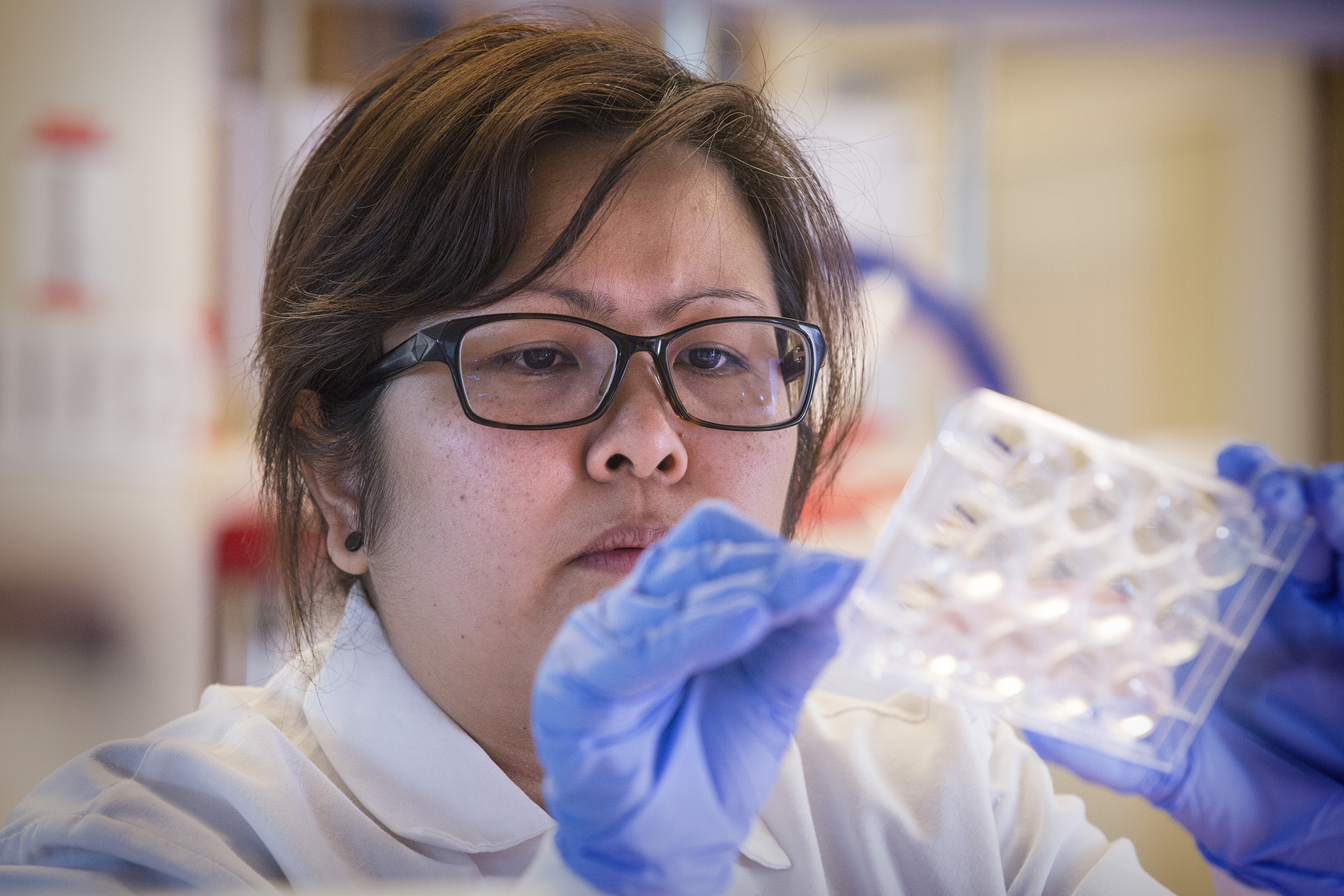

In 1999, Corey founded HVTN so that labs around the world who were conducting clinical trials for candidate HIV vaccines could collaborate on research.

HVTN’s main labs are located in Seattle, North Carolina, and South Africa, but the network now conducts HIV vaccine studies at over 80 clinical trial sites in 16 countries. The network has multiple trials in the field at any given time, with about a dozen studies currently underway, Corey told Global Citizen.

Before being tested in humans, all the vaccines are tested in small animals and non-human primates. Each initial trial, which lasts approximately nine months, involves around 30 to 50 participants who receive several injections during the study.

How mRNA Technology Is Accelerating Research

According to Corey, the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine technology — which was used in the development of COVID-19 vaccines — is helping accelerate the development of HIV vaccine candidates in “record time” by helping researchers get answers to their hypothesis during clinical trials in months instead of years.

“That creates a cadence for the field that is really very different than what we've had before — and that's where the enthusiasm is,” Corey told Global Citizen.

In July, participants were enrolled in a clinical trial which was one of the first HIV studies involving mRNA vaccine technology.

With major advancements with COVID-19 vaccines involving mRNA, researchers like Corey are hopeful that applying this technology to HIV studies will advance the development of an effective vaccine.

There are 10 participating clinical trial sites across the US.

For Corey, who has spent decades furthering research on HIV treatments and potential vaccines, these advancements leave him feeling hopeful that his “grandchildren can grow up in a world … where the potential of getting HIV is waned because we have a highly effective vaccine.”

Despite the technology, developing neutralizing antibodies — which is what researchers are working toward — is more difficult with HIV than other diseases. For example, unlike the COVID-19 virus, which most humans can clear from their body, the human immune response doesn't know how to cure HIV.

Dispelling Myths about HIV and Clinical Trials

Years ago, Kara Armbruster read an article where one man shared that at the height of the HIV epidemic, he lost 50 friends to the disease in a single year.

“That’s the line that got me,” Armbruster told Global Citizen.

She committed to doing anything she could to support eliminating infectious diseases.

Armbruster, who enrolled in the HIV vaccine trials study in February, wants to dispel myths about what’s involved — particularly for those who think clinical studies only involve “people in lab coats.”

She spends time dispelling myths by informing friends and family that the trial is non-invasive, only involves three injections and blood draws, and does not involve exposure to HIV.

Endlessly curious about science, Armbruster eagerly follows studies in Pittsburgh seeking participants. For the last 15 years, the former nurse has participated in two dozen clinical studies and hopes to play a small role in advancing scientific knowledge.

Galvan, who hopes for the same, believes an HIV vaccine will help destigmatize the virus.

Edward Galvan poses for a portrait in Chino Hills, Calif., on Nov. 28, 2022.

Edward Galvan poses for a portrait in Chino Hills, Calif., on Nov. 28, 2022.

“I do believe that a lot of people will start to see HIV as no longer this death sentence,” he said. “After so many years of struggles in the [queer] community being shunned and being told that this is our disease or our punishment — [a potential vaccine will bring] overall relief.”